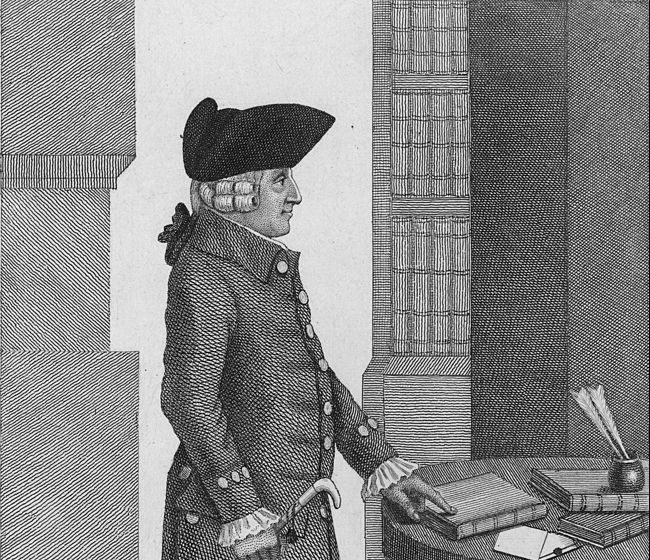

Adam Smith 300: Was the king of free market economics left-wing?

Was Adam Smith left wing?

Adam Smith is generally regarded as the father of modern capitalism. His works are cited by Milton Friedman, Friedrich August von Hayek and many other liberal and libertarian thinkers. Adam Smith, Friedman explained, “who but for the accident of having been born in the wrong century … undoubtedly have been a Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago.” The university was considered the center of free-market and libertarian thought.

But there is also a very different view of the Scottish moral philosopher and founder of modern economics. In a well-received essay, the British economic historian Emma Rothschild argued that Adam Smith’s thinking was at least as much a precursor of what has come to be known as “the left” as of what we now call “the right.” And the American philosopher Samuel Fleischacker stated in his essay “Adam Smith and the Left”: “Many scholars have made a case for left-wing tendencies in Smith.”

Libertarian criticism of Adam Smith

The sharpest criticism of Smith from within the libertarian camp came from the economist Murray N. Rothbard, who in his monumental work Economic Thought Before Adam Smith. An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, minces no words in his vilification of Smith, arguing that Smith was by no means the advocate of free-market economics he has commonly been portrayed as. Rothbard goes further. With his erroneous labor theory of value, Rothbard sees Smith as the forerunner of Karl Marx and claims that Marxists would certainly be justified in citing the Scottish philosopher and hailing him as the ultimate inspiration of their own founding father. According to Rothbard, Smith failed to understand the economic function of the entrepreneur and even fell short of the insights provided by economists such as Richard Cantillon, supported state-imposed caps on the rate of interest, high taxes on luxurious consumption and government intervention in the economy.

Distrust of the state

Much of this criticism is certainly justified, and yet it would be wrong to call Adam Smith a left winger, as evidenced by his deep distrust of government intervention in the economy and his almost boundless faith in the “invisible hand” that steers markets in the right direction. When the economy is ruined, it is, according to Smith, never by entrepreneurs and merchants, but always by the state: “Great nations are never impoverished by private, though they sometimes are by public prodigality and misconduct,” he wrote in his major work The Wealth of Nations. And he added optimistically: “The uniform, constant, and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition, the principle from which public and national, as well as private opulence is originally derived, is frequently powerful enough to maintain the natural progress of things toward improvement, in spite both of the extravagance of government and of the greatest errors of administration. Like the unknown principle of animal life, it frequently restores health and vigour to the constitution, in spite, not only of the disease, but of the absurd prescriptions of the doctor.”

The metaphor says a lot: Private economic actors represent healthy, positive development, while politicians obstruct the economy with their nonsensical regulations. Adam Smith would have been very skeptical today if he could see governments in Europe and the United States increasingly intervening in the economy and politicians who believe they are smarter than the market.

“Every individual,” Smith wrote in his magnum opus, “is continually exerting himself to find out the most advantageous employment for whatever capital he can command. It is his own advantage, indeed, and not that of the society, which he has in view. But the study of his own advantage naturally, or rather necessarily, leads him to prefer that employment which is most advantageous to the society.” Legislators, Adam Smith believed, should have more confidence in the fact that “every individual, it is evident, can, in his local situation, judge much better than any statesman or lawgiver can do for him.”

Resentment of the rich, respect for workers

Perhaps the view that Smith was a left-winger also stems from the fact that he repeatedly directed stinging criticism at merchants, entrepreneurs and the rich while passionately advocating better conditions for workers. There are many passages similar to the following in his great work: “Our merchants and master-manufacturers complain of the bad effects of high wages in raising the price, and thereby lessening the sale of their goods both at home and abroad. They say nothing concerning the bad effects of high profits. They are silent with regard to the pernicious effects of their own gains. They complain only of those other people.” Or: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

Every individual, it is evident, can, in his local situation, judge much better than any statesman or lawgiver can do for him.

Defenders of Smith argue that these passages do not reflect any resentment against entrepreneurs or the rich, but Smith’s advocacy of free competition and opposition to monopolies. That is certainly one aspect, but nevertheless his two major works create the impression that, basically, Smith dislikes the rich as much as he dislikes politicians. Even Adam Smith was not free of the resentment traditionally harbored by intellectuals and educated citizens against the rich.

Empathy as the cornerstone of Smith’s moral philosophy

Another thing Smith did not understand was the economic function of the entrepreneur, which was later so brilliantly elaborated by thinkers such as Joseph Schumpeter. Smith mistakenly saw the entrepreneur primarily as a manager and business leader rather than as an innovator.

“Sympathy” is the cornerstone of Smith’s moral philosophy and he begins The Theory of Ethical Sentiments by outlining the utmost importance of his concept of sympathy. Today we would use the word “empathy” rather than “sympathy” to describe this ability to understand and appreciate the feelings of others.

Smith recognised the importance of empathy, but he did not connect it with entrepreneurship at any point in his work. Today, we see in Steve Jobs and other entrepreneurs who understand the needs and feelings of their customers better and earlier than the customers themselves, that empathy – and not “greed” – is indeed the basis of entrepreneurial success and the foundation of capitalism.

Smith’s failure to understand the role of the entrepreneur and his evident resentment of the rich are indeed characteristics that Smith shares with those on the left of the political spectrum. However, this does not at all apply to his advocacy of improved conditions for workers. For, according to Smith, improving the situation of ordinary people would not come about through redistribution and excessive state intervention, it would be the natural result of economic growth, which in turn needed one thing above all: economic freedom. To the extent that economic freedom prevails and markets expand, people’s standard of living will also rise. Three hundred years after Smith’s birth and some 250 years after the publication of his magnum opus, we know that the moral philosopher and economist was right.

Rainer Zitelmann is a historian and sociologist. His latest book is In Defence Of Capitalism