A tribute to Martin Amis: ‘He wanted time itself to flow backwards’

Last weekend Martin Amis died in Fort Worth, Florida at the age of 73 – the same age as his father Sir Kingsley Amis – of a disease I hadn’t known he had, in a house I wasn’t aware he had owned.

Why should the death of our heroes be so shocking, being as it is the surest fact about the world? Partly, it is because we’re deprived of the context of decline. Death has its logic lived one moment at a time: Amis’ smoking and drinking are explanations we look for amid the fact of coming to terms with it all. We have to play catch up mid-grief – we scrabble for information as we mourn.

I can still remember Amis sitting to one side of Christopher Hitchens during one of the latter’s last TV interviews, swigging a bottled beer while his friend, bald from chemotherapy, talked so brilliantly in the face of death. Hitchens looked vulnerable, but Amis appeared separate from his friend’s situation. Now we must assimilate that these past years Amis had been silently dealing with the same illness.

Separated from cause like this, Amis’ departure leaves us with the shock of an unsubstantiated absence. In the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, we have come to expect immortality from our literary greats. It was John Updike who expressed his surprise at Nabokov’s death by saying he had ‘imagined him exempt’.

I don’t think our regard for Amis ever quite partook of the awe which he – and others – felt for the author of Lolita. It was Amis’ fate to be obviously brilliant, but also to be widely disparaged and belittled.

There were many reasons for this. One was his physical stature: always, in his own words, ‘a short arse’ he was also characterised by Christopher Hitchens as ‘little Keith’. Given who his father was, it was possible to miss the scale of his achievement. “Daddy does it better,” was a bright friend of mine’s verdict, and one I doubt he would consider revisiting.

Yet now, in his obituaries, Martin is a ‘literary giant’, amid all the other newspaper banalities: the ‘Mick Jagger of literature’, the ‘enfant terrible’ and so forth. “Why don’t people ever refer to Mick Jagger as the Martin Amis of rock and roll?” he once opined.

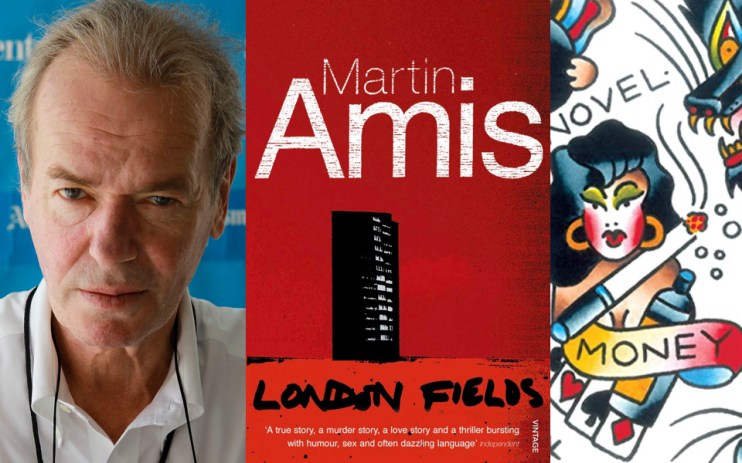

But we now experience the sudden sweeping away of all the nonsense that was written about him. The somewhat overblown controversies recede – things Amis said about Islam, about how he’d have to be brain dead to write children’s books, or silliness surrounding his teeth. All this exaggeration and ad hoc explaining rushes aside to be replaced by the work he did at the desk: Money, London Fields, Experience, The Zone of Interest (a film of which was showing at Cannes in the week of his death), The House of Meetings, Success, to name only a few.

These are what matter but one wonders if they will matter enough. On BBC News, Amis’ death came second throughout Saturday to the departure of Phillip Schofield from ITV’s This Morning – a pretty vivid example of the insanity which Amis had spent his life railing against. But as Auden put it: “Poetry makes nothing happen.”

Writers will look at the death of a fellow writer – especially one so eminent as Amis – and pause in their next day’s work, wondering if it’s all worth it. Amis himself knew this feeling, and articulated it definitively in his 2009 tribute to John Updike: “Several times a day you turn to him, as you will now to his ghost, and say to yourself ‘How would Updike have done it?’ This is a very cold day for literature”. So it goes today.

But already at his death, Martin Amis was read less than at any time in the last 50 years. There wasn’t a great fanfare around 2020’s Inside Story – presumably his last novel unless something comes to us posthumously. This may have been because, in retrospect, he was too ill to conduct too many interviews. But he had undeniably begun to run out of steam. That last book – in many respects a rewrite of 2000’s memoir Experience – felt bloated, the sign of a writer returning to material – his father, his friendships with the American novelist Saul Bellow and Christopher Hitchens – which he’d already satisfactorily dispatched.

In a sense then, his death comes with this compensation: Martin Amis got himself expressed. Well then, what did he say?

As numerous obituarists have pointed out, he said first of all that what he was saying was of less importance than how he said it – or more, what he was saying was how he said it. Sometimes, as in his great collection of journalism The War Against Cliché, he pointed this out very precisely – but all along it was the subtext of every sentence he wrote.

Can this commitment to style be taken too far? Christopher Hitchens recounts how Amis refused to go on past the first page of Orwell’s 1984 because of the early line describing the Stalin figure as ‘ruggedly handsome’. It could be argued that to miss out on 1984 because of this was a step too far: he sometimes acted as though writing was only style. “Style isn’t neutral; it gives moral directions,” he once said.

This equilibrium in the Amis style loops back to his fundamental delight at his choices in life. He loved his job and his work, and never seriously deviated from it, unless one counts his foray into screen-writing with Saturn III, which abortive experience was immediately scooped up in the terrific gift of his masterpiece Money.

What did writing mean to him as a career? Amis once described writing as “a sort of sedentary, carpet slippers, self-inspecting, nose-picking, arse-scratching kind of job, just you in your study and there is absolutely no way round that. So, anyone who is in it for worldly gains and razzmatazz, I don’t think will get very far at all.”

In fact, Amis was so famous so young that he could have spent his life at parties. Zachary Leader has recalled that Amis, always kind to his friends, never mastered the art of saying no politely to invitations.

But if there were hurt feelings, I think we can let those lapse now: the most important word in a writer’s vocabulary is ‘no’ – and had Amis not used it so much we might not have London Fields. As he once said in relation to the emotional response of one of Bellow’s friends who didn’t like the way he’d been depicted in one of the master’s novels: “Well, that’s just tough.”

What else does the Amis style point towards? There were the piled-up lists of horrified noticing, which are often allied to disgust at modernity: Amis was really a romantic at heart, appalled at this postlapsarian world. This rhythmic rage was identified by John Updike in his review of Night Train (1997) – the critical mauling which hurt Amis most – as a ‘typical burst of Amis lyricism’. This trope was there from the beginning in this depiction of a street in 1973’s The Rachel Papers, which is seen as containing: “demonically mechanical cars; potent solid living trees; unreal distant-seeming buildings; blotchy extra-terrestrial wayfarers”. This brash listiness repeats throughout the oeuvre and is Amis’ way of showing how the ugliness of the world appears to be piling up exponentially, and can only be mitigated by being named – only when you do that do you begin to bring things back under control.

This, then, is the Amis disgust, and in his worst novels this emotion could seem synonymous with a dislike of the working classes. There will always be those who think that he was dismissive about people with whom he could claim at best a slender acquaintance. On the other hand, he was creating a fictional universe not writing government policy, and those who read him as if they don’t know the difference will probably never enjoy a comic novel.

Amis wrote much about the importance of a writer being generous to readers – by which, he appears to have meant being intelligible. For him Ulysses was too difficult, and Finnegan’s Wake an absurdity; even his own beloved Nabokov strayed into error with his late book Ada. My least favourite of Amis’ books for similar reasons is Time’s Arrow, a Holocaust story told backwards, and which gave me a migraine. But it was a brilliant idea even if it could never have been a readable book.

I’d say that by the midpoint of his career, Time’s Arrow tells you all you need to know about Amis and the future – he didn’t welcome it, and wanted time itself to flow not forwards, but backwards. Again, he had his reasons. Most people who truly love writing know that the future can’t be everything it’s cracked up to be: Shakespeare died 407 years ago.

Amis gives us a Britain – and then an America – in decline. Some have said that especially in Money, Amis depicts the excesses of late capitalism, which is true insofar as it goes, except that we don’t know how near its death capitalism really is. For all we know, it might be that he is the chronicler of its stodgy middle period.

At any rate, Amis seems to be sitting too comfortably to one side of societal decay, regarding it. It’s always possible that someone may have some vast private George Michael-esque habit of philanthropy, but I find it hard to imagine Amis rolling his sleeves up to fix a problem; the idea of him ever running for office like Gore Vidal or Norman Mailer is palpably absurd. But perhaps there’s never been anyone better at describing the problems themselves.

Even so, this sane opting out made politics a difficult subject for Amis. Something about history – though it fascinated him – didn’t sit easily with him creatively. This might be because he was a very sensory writer, and the past is out of reach. Gore Vidal – who Amis wrote brilliantly about – understood the past instinctively, but Amis can’t write about the past without straining after significance.

It is the self-consciousness of taking on big topics which appears to get in the way of what he elsewhere regards as the crucial business of perception, which then leads necessarily, because the world is funny, to comedy.

He once said that he continued to write about the Holocaust because he hadn’t come to understand it yet. This need to assimilate the unthinkable is really a sort of refusal of mysticism, and therefore a dead end. There has to be mystery in writing; it is the unseen energy which harnesses the instinct to do it at all.

Amis couldn’t leave evil alone as a thing which just is and requires no special or new explanation. There has always been a strand of Judaeo-Christian thinking which regards the devil as essentially boring. Amis wasn’t at all of that tradition. In his best books he floated free of it in the comic mode. But when he sought to take on the Nazis or Stalin, he was rudderless.

Similarly, he had no particular interest in goodness either. In this, as in much else, he is similar to Dickens, whose villains are vivid, but whose heroines – think Esther Summerson in Bleak House – simper, as if goodness can’t ever have convincing embodiment. Updike wrote in that same review of Night Train that Amis’ fiction ‘lacks positives’. Though Amis always stopped short of Hitchens-style atheism, arguing that it sounded like a ‘proof of something’, there may have been something ultimately a bit watery about his worldview which led to a somewhat unmoored intellectual life. This is what ultimately weakens the work undertaken outside the genre of comedy.

But how wonderful he was when he was doing what he was best at. I think of the uproarious descriptions of Marmaduke in London Fields; of his description of Updike as a ‘psychotic Santa of volubility’; of the ‘nylon rain’ in Success; of the filmed sex scene in Money (‘You’re a tremendously ugly man, John’); his description of accompanying Blair during the end of his premiership, and finding himself becoming ‘mildly flirtatious’ with the PM; the idea in Experience, of Kingsley Amis’ last fall being a thing of ‘colossal administration’; and his great eulogy to Christopher Hitchens, to my mind the greatest speech by far of the post-War period in an admittedly poor period for orations generally.

We go to Amis not to meditate on the complexity of the world, but for joyous laughter. And in this serious world there is sufficient dearth of that to make his passing an event very far from neutral: it’s time to go with delight and love back to the books. But as we do so, let’s ask ourself what the style pointed towards.

• The full version of this article first appeared in finitoworld.com