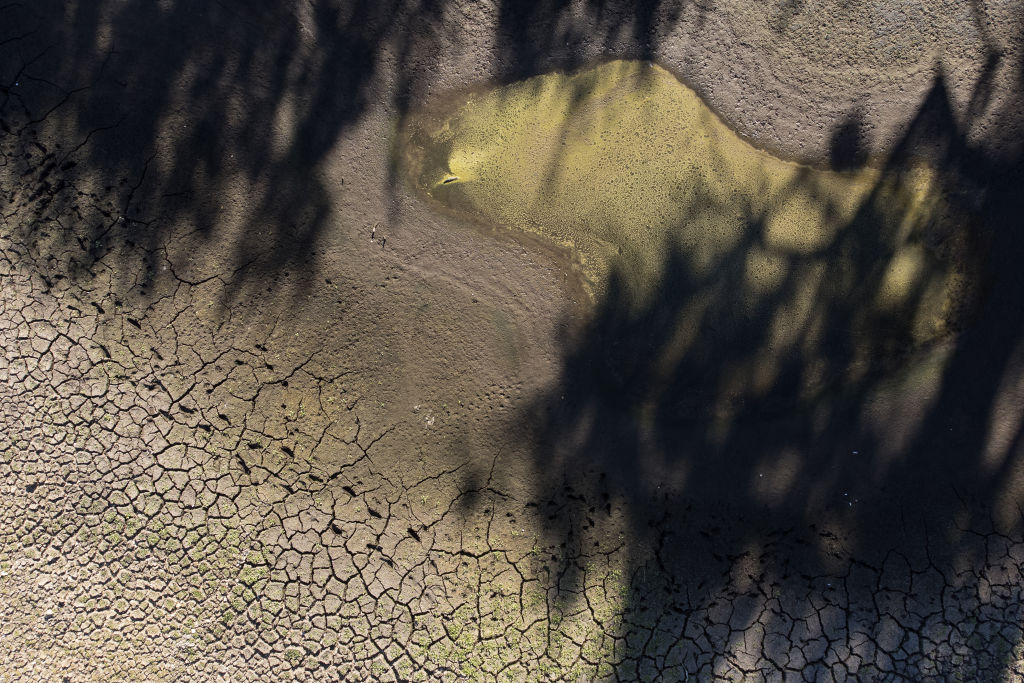

A drought of willpower: The UK’s struggle to meet its water needs

Tankers and Thames Water workers descended on Northend, Buckinghamshire last month to drop off emergency crates of bottled water to residents after the summer heatwave and technical problems drained the local Stokenchurch Reservoir.

Thames Water bore the brunt of criticism for the crisis, with aghast villagers frustrated over years of perceived negligence and warning signs, now being left unable to shower, flush toilets or pour a glass of water.

The company has certainly done itself no favours to its reputation in recent years, with regulator Ofwat slapping it with an enforcement notice for suspected sewage dumping in March, while it also has admitted to leaking 600m litres a day, around a quarter of its overall supplies due to creaking infrastructure and ageing pipes.

Nevertheless, the crisis in the village of Northend is reflective of a wider problem – which is that for over three decades, the UK has not built a new reservoir for water supplies.

Summer heatwave exposes Britain’s creaking water infrastructure

To most people, the driest July on record with all-time high temperatures of 40.3 degrees Celsius meant yellowed lawns, sweaty commutes and hosepipe bans.

However, Water Resources South East (WRSE) – a group of six water companies operating in the South East including Thames Water – have warned such heatwaves could have more significant consequences in the future.

The group has forecast a 1bn litre per day shortfall of water across the region by 2040, rising to 2.6bn litres per day by 2060 without fresh sources of water.

It has calculated an £8bn cost to avoid a shortfall in water supplies in the South East in the next two decades, which could climb as high as £17bn by 2060.

A spokesperson for Thames Water said: “Water resources in the south east are under severe pressure due to population growth, impact of climate change and the need to protect and preserve sensitive watercourses. As custodians of the environment, we take our responsibility to protect and enhance it extremely seriously while also ensuring our customers have a secure and sustainable water supply now and for future generations.”

WRSE is pushing for an action plan to manage resources as far into the future as 2075.

One of its proposed solutions is a potential super-reservoir in Abingdon – which would be built less than 20 miles away from Northend.

Abingdon reservoir: Super project or super waste of resources?

The £1.4bn project could provide 100m litres of water a day, putting a big dent in the estimated shortfall over the coming decades.

It could feed the supply areas of multiple companies including Thames Water – locally and in London – Affinity Water, Southern Water and potentially also South-East Water.

Plans for a reservoir in Abingdon were first proposed in 1996 but were objected to at the time, with the scheme also facing local opposition in 2009 and 2019.

Local MP Layla Moran has also raised concerns over the project.

Currently, Moran sits in the swing seat of Oxford West and Abingdon, which has switched between her party, the Liberal Democrats, and the Conservatives three times since the reservoir was proposed.

Moran argued Thames Water should focus on fixing leaks before committing to such vast projects, describing their current proposal to build a mega-reservoir like “building a bath with no plug in it.”

She also believed residents should be able to assess alternative plans for a mega-reservoir.

Other ideas currently being proposed by WRSE include building a pipeline or canal transfer from the River Severn to the River Thames, and recycling water – treated from the sewerage system.

Emily Fielder, head of communications at Adam Smith Institute argued the Government should consider financial incentives to ensure key projects can be greenlit.

She said: “Kwasi Kwarteng’s pledge to accelerate the construction of vital infrastructure projects through a liberalisation of the planning system is certainly welcome, but he must ensure to counter local objections, perhaps through financial incentives.”

Government lays down gauntlet for change

During the Chancellor’s eye-catching fiscal event last week – a ‘Kwasi-budget’, some would argue – Kwarteng laid down the gauntlet for a serious overhaul of the planning system to “get Britain building again.”

He argued the current planning system for major infrastructure was “too slow and fragmented” and that the Government would have to streamline the process after decades of infrastructure projects being frustrated.

BEIS did not comment on the reservoir when approached by City A.M., but Kwarteng’s Growth Plan features new legislation, such as the Planning and Infrastructure Bill, to accelerate priority major infrastructure projects across England.

This includes minimising the burden of environmental assessments, making consultation requirements more proportionate, reducing habitats and species regulation; and reforming development consent orders.

Ofwat told City A.M. the proposed reservoir has gone through the early stages of the Regulators’ Alliance for Progressing Infrastructure Development (RAPID) process.

This where large infrastructure projects are checked at specific points along the development process to ensure sufficient progress is made and whether they should receive ring-fenced funding.

Meanwhile, a new consultation has since been prepared by WRSE for mid-November, where locals can make their views known about its regional plans.

With the consultation running until February 2023, the touted project and its potential greenlighting falls within the timeframe of Liz Truss’ Government, well before the next election.

The Abingdon reservoir could therefore be a key litmus test for her reforming zeal and political willpower and whether Government action will match its rhetoric.