A £300m planning application 249 times the length of War and Peace? Meet the man delivering the £9bn Lower Thames Crossing

Matt Palmer is no stranger to contentious infrastructure projects.

His more than 30 years of experience in the sector has involved stints on Heathrow’s embattled third runway proposals and heading up the delivery of the Hounslow hub’s Terminal 5.

The latter project, which successfully produced the largest free-standing structure in the UK, prompted calls for reform of the planning system due to the size of its application.

Palmer, who is now tasked with delivering the £9bn Lower Thames Crossing (LTC) to the east of London, would be forgiven for thinking it was Groundhog Day.

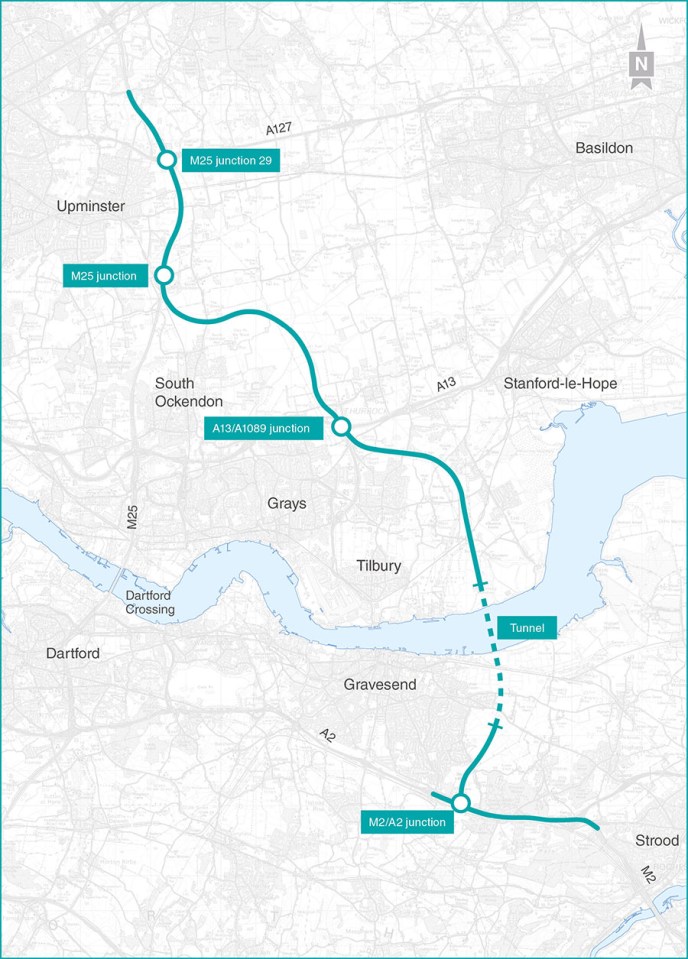

The planning application for the 14-mile long road and tunnel, which aims to relieve traffic from the highly congested Dartford Crossing, is the UK’s longest ever at a whopping 359,000 pages and costing nearly £300m, before a spade has even touched the ground.

Laid end-to-end, the document would reach 66 miles in length. By page count it is over 200 times longer than any of War and Peace, the Lord of the Rings trilogy or the Bible and more than 100 times longer than all seven Harry Potter books combined – take your pick.

Palmer is optimistic though. Chatting with City A.M. near the Dartford Crossing, he explains the time and cost comes down to hitting stringent environmental targets, as well as extensive consultation on the detail so hurdles don’t crop up down the road.

“A large proportion of that is about making the scheme better… For a scheme that’s nearly £9bn, I don’t see that as an astronomical cost. I see it as the right cost, as long as the scheme goes forward,” he said.

Critics may yet eat their words. Problems at HS2, a symbol of the UK’s failing infrastructure system, have been put in part down to a slapdash approach to its planning and business case, as well as politicians’ over-optimism in the early days.

Palmer noted the scheme’s environmental impact assessment “is where the bulk of our resource has gone. It is about understanding where we’ve got species we need to worry about and how we mitigate those [impacts].”

“Whether it be bats, whether it be newts, whether it be impact on health. All of those are really, really vital, essential, and we need to do so.”

That said, no one can deny that a 359,000-page planning application, which could well be the longest ever, doesn’t point to serious issues in the UK’s infrastructure landscape.

What’s causing the hold up?

Visiting the Dartford Crossing at peak hours, it is clear something needs to be done. A 300-strong team, the largest of its kind in the UK, works 24 hours a day, 365 days a year to keep it open

It is currently the only route across the River Thames to the east of London and is regularly overloaded with traffic, while the control room resembles something akin to an airport’s air traffic control tower. Almost two in three journeys via the crossing take more than double the time they should.

An escort system for abnormal loads and dangerous goods caters for the huge number of freight and heavy goods vehicles who journey to and from the main ports in the south-east. But it means one of the tunnels closes on average once every 15 minutes during peak times.

So why is the Lower Thames Crossing, which would reduce traffic by nearly a fifth, taking so long to get off the ground?

Part of the problem rests at the local level, Palmer said. “The planning system has elongated… We are dealing with local authorities that have got other things to do and they’re not well funded, they’re not strategic.”

Both Kent and Essex have backed the project in the past yet their positions are subject to change with elections. Bring in smaller local authority opposition from the likes of Gravesham and Thurrock and a drawn-out process is inevitable.

Each group brings their own set of interests to the table. Thurrock opposes the scheme yet its priorities are arguably clouded by a major financial scandal, which saw it declare bankruptcy in late 2022 after running up one of the largest losses in local government history.

The DCO process was brought in in 2008 to streamline the UK’s approval process for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIP). It is now facing significant backlash, with delays to decision-making increasing eight-fold since 2016 amid a failure to cut red tape.

Swung by the cycle

There are far wider problems though, according to Palmer, which explain much of the malaise gripping many British infrastructure projects.

“My starting point is always certainty,” he told City A.M. “It’s that long-term fixation. Know what you want, know which way you want to build your economy, and then pursue it over time, and you pull the projects off.”

“In the UK, what we have in more democratic worlds, whether it be in Europe, so Germany, France, or us, or even in the States, is you tend to get swung more by the political cycle.”

A turbulent political system over the last few years has fallen alongside a huge increase in UK government debt, which reached over £2.54trn in 2022/23, compared with £2trn in 2019/20.

“The new problem in the UK is this macro funding problem, and you’ve seen it with Hinkley on nuclear power, it’s happening on Sizewell, it’s happening on HS2. How does the government afford its big infrastructure? And should it be government paying or should it be private paying? And we need to solve that.”

Beleaguered HS2 is currently looking for private investors to guarantee it reaches Central London and Palmer told City A.M. he would support a similar approach at LTC. “It’s as viable an option as public finance,” he said.

“Any government is going to really struggle to try and fit us into the portfolio going forward, that’s not to say they’re not committed to doing it, they are. My worry is… how strapped government finance is, that’s going to be a really difficult obstacle.”

As uncertainty over the viability of major projects grows, problems are compounded by falling confidence in the system.

“We’ve not got a lack of capability or professionalism in the UK. It’s just that actually everyone else wants it and has got it… So all our talent is overseas, because we just don’t pay enough,” he said.

It paints a bleak picture of Britain’s current infrastructure landscape and following the cancellation of HS2’s northern leg in October, confidence has never been lower.

But Palmer, who joined the sector out of a firm belief in the social importance of major projects, is staying put. “I became an engineer to do social good. I think we can literally build a better world,” he told City A.M.

The LTC is the first infrastructure project to commit to a legally binding carbon limit on its DCO, which it is seeking to achieve through low-carbon hydrogen.

“We’re going to try to knock the socks off everything in terms of bringing, whether it be biodiversity, whether it be carbon, a sustainable legacy in terms of jobs, etc,” Palmer said.

The hurdles are significant though and with a general election looming, uncertainty is likely to persist for the foreseeable future.

A legal challenge is near-guaranteed, while its colossal planning application has drawn widespread media headlines in recent weeks.

And all while costs continue to creep up, from an initial estimate of around £5.3bn to the current forecast of £9bn.

Palmer and his team will have a fight on their hands to keep publicity positive.