Why significantly extending the Living Wage is not the best way to help the poorest

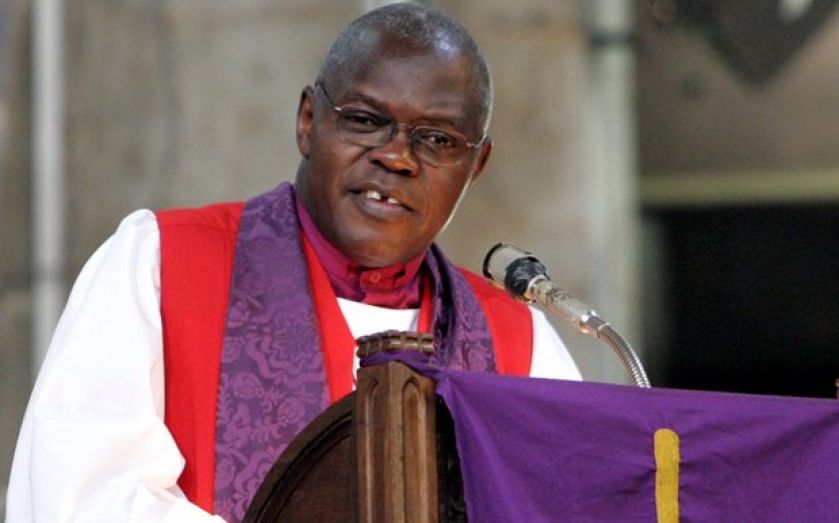

JOHN Sentamu, the charismatic archbishop of York, has again thrown his weight behind the recommendations of the Living Wage Commission he chairs. Not to be confused with the government’s Low Pay Commission, which recommends the statutory minimum wage, the Living Wage Commission is a private pressure group funded by trade unions and faith organisations.

Its latest report calls for 1m more workers to be paid the Living Wage, currently £7.65 an hour nationally, and £8.80 in London, by 2020. The principle of raising low pay is laudable, and the report is in some ways thoughtful, recognising the risks to jobs that a compulsory Living Wage would bring. It sees the way forward as requiring government work to be paid the Living Wage, with “they-can-afford-it” private sector employers (in finance, IT and professional services) encouraged to step up to the plate. It would also like to see public sector procurement play a major role, with contractors under pressure to raise pay.

The 2020 target is new: however there is little else that is novel. As I have written before, as long as the Living Wage is an aspiration, paid by firms that can afford to do so, it will do little damage. But it’s worth pausing before accepting the Commission’s assumptions without question. It has a model of the labour market that reflects prejudices against employers, misunderstanding of the role of entry wages, and the dangers of unintended consequences.

It emphasises the link between low wages and poverty; the archbishop says that, “for the first time, the majority of people in poverty in the UK are now in working households”. But this is misleading in two ways. First, few of these poor working households have members working full time. Three-fifths of those receiving less than the Living Wage are working part time. In this sense, the Living Wage idea is flawed, for if those receiving hourly pay hikes are still only working relatively few hours, they will not be lifted out of poverty.

Second, those on low wages are not necessarily in poor households. IFS data show that 44 per cent of those earning less than the Living Wage are in households in the top half of the income distribution, and 5 per cent live in households in the top decile.

So the Living Wage is a poorly-targeted anti-poverty measure, which attempts to load the cost of reducing poverty onto employers, and thus consumers – many of whom are not well-off. It also creates collateral damage to job opportunities, particularly for the young. The report has no clear view of how young people are to be treated in a Living Wage regime. Is there to be a youth rate, as with the minimum wage? If not, an 18-year old in London would receive a pay rise of over 50 per cent. It beggars belief that hikes of this size would not lead to higher youth unemployment, as firms substituted more productive workers.

The Commission’s analysis remains static, largely ignoring knock-on effects such as pay rises for those currently on or above the Living Wage with more experience and responsibilities, and firms choosing to substitute capital equipment for labour if wage costs rise.

To mitigate such effects, it prays in aid wishful thinking about productivity increases and reduced absenteeism, unlikely to accrue to the employers the Commission targets. There are also references to possible multiplier effects and fiscal gains, through lower in-work benefits and higher tax take, which depend on contestable assumptions.

Overall, there is nothing new here to convince sceptics that the Living Wage is the best way to relieve poverty and boost productivity. Sentamu is a terrific archbishop, but a less than convincing policy analyst.

Len Shackleton is professor of economics at the University of Buckingham, and economics fellow at the Institute for Economic Affairs.