Which came first, the wizard or the app?

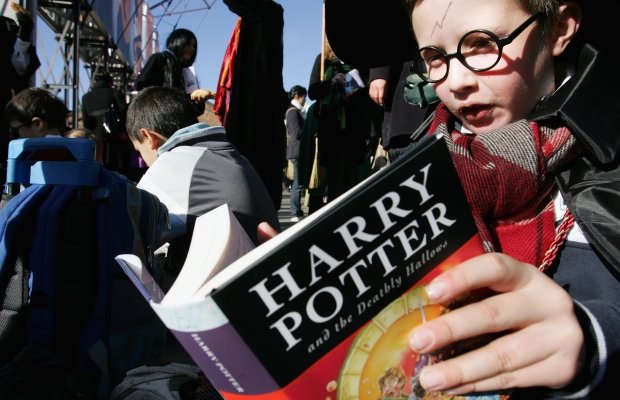

For four years, Harry Potter lived only in the pages of a book.

Between The Philosopher’s Stone being published in 1997 and its film adaptation coming out in 2001, the face of the bespectacled wizard existed only in the imaginations of those who had read JK Rowling’s novels (or at least seen the cover art).

But for anyone born after the first film came out, Harry’s face is the same as Daniel Radcliffe’s – the actor who played him in all eight adaptations from the age of 11 to 21.

Today, children don’t have to pick up a book, or even watch a film, to meet Harry. He’s on their smartphone or tablet as part of a Warner Brothers spell casting app; on their console as the star of an EA video game; and just north of Watford Junction as part of the studio tour that opened last year.

But apparently that doesn’t mean they’re not reading about him too. A new study by Professor Keith Topping for Renaissance Learning has claimed that not only do these multi-channel tie-ins lead children back to the original paperback Harry Potter series – they actually encourage them to start reading more challenging books at a much younger age.

After using software to analyse the length and difficulty of words and sentences in books, the study then quizzed children on their understanding of a text to see how accurately they had taken in information.

Most kids from the ages of five to 10 scored between 88-93 per cent, indicating a high level of understanding of their most-loved books – despite their choices being on average 2.4 years above the level expected from their chronological reading age.

Of those most-loved – from Harry Potter and The Hunger Games to JRR Tolkein’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings series – almost every one had been turned into an animated film, app, computer or online game.

“In an increasingly multi-media world, these findings suggest that technology can support literacy, rather than acting as a distraction,” said Dirk Foch, managing director of Renaissance Learning.