The Long View: JK Rowling’s pseudonymous success is a triumph for democratic publishing

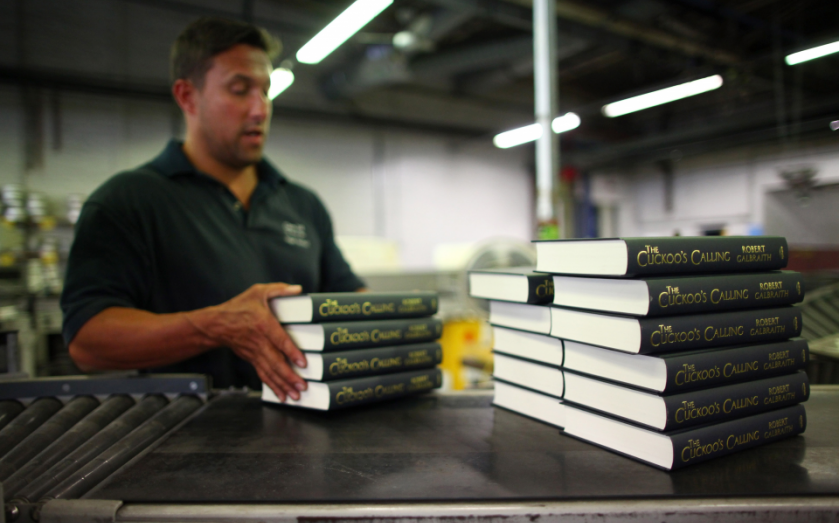

I DON’T know why I’m bothering to write this. It’s not like Marc Sidwell is a pseudonym for JK Rowling. Few will have missed the recent overnight journey of Rowling’s pseudonymous crime book The Cuckoo’s Calling from bargain bin to the top of the bestseller lists once she was revealed as the author. Apparently not a cunningly timed publicity stunt but a genuine scoop, the story has been read by many as a fairytale gone wrong: a sign that only celebrity can succeed in the modern publishing world.

But this idea is pure fiction. If it wasn’t, Pippa Middleton would be celebrating the umpteenth printing of her party planning book. Instead, it’s at the bottom of the charts and she’s reduced to setting her lawyers on the upstarts behind parody Twitter account @pippatips, who have brought out a book of their own which looks set to do distinctly better business.

It is true that the internet tends to favour the exceptional success of a few. There’s nothing wrong with that. As web guru Clay Shirky pointed out back in 2003, the disproportionate success of a few is the hallmark of a highly democratic system that maximises free choice: “Diversity plus freedom of choice creates inequality, and the greater the diversity, the more extreme the inequality.”

If we value diversity, we have to learn to accept the variety of outcomes it implies. Rowling’s outsize success is really a proof of how open the web has made publishing. Her success doesn’t exist at the expense of others – a point that should be obvious if we only consider the extraordinary recent growth of self-publishing. Her success simply reflects the natural structure of a diverse and open marketplace.

If Rowling’s experience proves anything, it is not the death of opportunity in publishing, but the death of the traditional gatekeepers that closed opportunity down. Rowling herself first came to prominence not because of publishing muscle but word of mouth. Today, thanks to the internet, no author needs a publisher’s permission to seek an audience for his or her work.

The opinion of a narrow caste of reviewers counts for less and less as well. The Cuckoo’s Calling was well reviewed, but sales of 1,500 copies suggest that had little impact. And with bookshops also in decline, publishers’ ability to buy promotional space for designated bestsellers is also falling away.

Meanwhile, there are stories like that of Regina Sirois. Warned off by literary agents, who said her young adult book On Little Wings was “too intelligent” and lacked a market, she uploaded it to Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing platform. The free ebook was downloaded 14,000 times in five days, generated terrific reviews, and Sirois then sold 12,000 paid copies in just a few months. Today she is working on her third novel.

The idea that huge celebrity for any author is bad news for those of us who love writing and reading is foolish. A publishing ecosystem without tall poppies would be less diverse and less fertile. Authors would have to queue again for the rationed mercy of a few agents, publishers and critics. Readers would be less well-supplied with the books they wanted to read. As with the wider economy, so with publishing: fantasies of a more equal system turn out to have unhappy endings.

Marc Sidwell is managing editor at City A.M.