No interest rate increase for at least another year

INTEREST rates will not rise for at least a year, the Bank of England indicated yesterday, despite the rapid recovery and falling unemployment.

Even when rates do rise they will remain well below pre-crash levels for many years into the future.

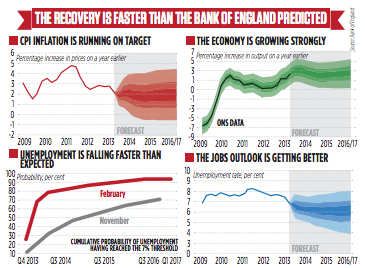

Governor Mark Carney hiked GDP forecasts for 2014 from 2.8 per cent to 3.4 per cent, but insisted the economy remains “fragile” and said he “will not take risks with the recovery.”

“For a sustained and balanced recovery, the degree of stimulus will need to remain exceptional for some time,” the governor said.

Six months ago Carney said he would start looking at raising rates when unemployment fell to seven per cent, which he expected in 2016.

But joblessness is already near that level, prompting a stark turnaround from the Bank of England.

Instead of looking at raising rates, the monetary policy committee will now wait until spare capacity – the gap between output now and where it thinks output could be – disappears.

Carney admitted this is hard to measure. Last year the MPC opposed this measure, calling it “unobservable and difficult to explain.”

The Bank estimates the output gap is currently between one per cent and 1.5 per cent. It expects to shut the gap over two to three years, indicating it will be more than a year before rates even begin to creep up.

The Bank believes most of the gap is in the labour market, and will estimate it by looking at metrics including total hours worked, wage growth and unemployment.

Economists fear this policy will be more difficult to understand and could hit the Bank’s credibility.

“The revised forward guidance has become even more complex and provides little clarity on the key issue of how the MPC will manage the process of raising interest rates,” said former policymaker Andrew Sentance.

“If the economy continues to grow, the emergency policies put in place five years ago will become increasingly inappropriate. This policy carries the danger that when rates do rise, they will do so quite sharply.”

WHAT HAS CHANGED?

The economy is growing faster than expected – the Bank of England raised its GDP forecast for this year from 2.8 per cent to 3.4 per cent and trimmed its inflation forecast to remain at the two per cent level for several years.

The recovery has pushed unemployment down to around seven per cent, forcing the Bank to update its interest rate guidance.

Last August the Bank of England said it would not consider raising interest rates until unemployment fell to seven per cent.

It thought that would take three years. In fact it took about six months.

Instead of raising rates, the Bank will now target the output gap.

To gauge this it will look at a range of indicators like productivity and firms’ estimates of their output potential.

The Bank had shied away from this in the past because it is notoriously hard to measure the output gap.

When the gap – currently estimated at one to 1.5 per cent – is almost down to zero, the Bank will raise rates.

It fears raising rates sooner would hit the recovery.

But if it raises rates too late inflation will rise.

Economists see this move as a return to inflation targeting, the main policy used before the financial crisis.