3 reasons for the achingly slow progress on EU-US free trade deals

Though a stock-taking meeting for the US-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) begins again today, progress is likely to be painfully sluggish.

Transpacific talks have gone through 18 rounds already, not including meetings between ministers or chief negotiators. In comparison, the EU and US not yet even the third round of talks, which are already grinding through political difficulties.

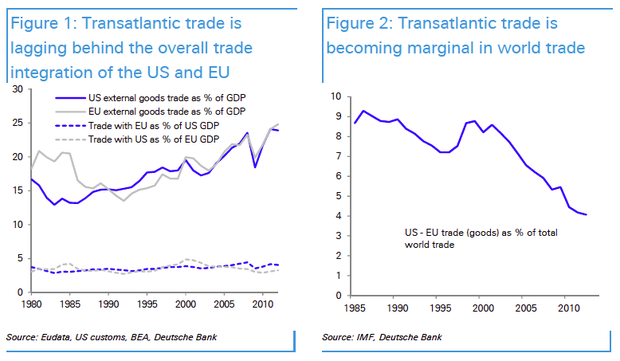

Though EU-US trade is becoming a much more marginal issue in the context of world trade, there is still room for improvement, which the Centre for Economic Policy Research suggests could increase UK national income by £4-10bn annually.

(Source: Deutsche Bank)

But Deutsche Bank researchers don’t expect results to come “in time to have a meaningful impact on the current economic difficulties of the two regions”, and political turmoil could yet derail an agreement entirely. Here’s why.

EU backing is fragile

Despite the early days of the talks, there are already obvious issues emerging from the European side – the French film industry has forced in commitments that “cultural exceptions” negotiated in world trade talks will continue to be protected.

French President Francois Hollande has also raised the eavesdropping of US security services on EU leaders as something that could derail the talks – whether this is a real reason for ending negotiation or not, it may prove a useful method to bail on discussions if any EU leader gets cold feet.

Deutsche’s Giles Moec added: “The political hurdles around the deal are very high. After five years of crisis, support for “free market” mechanisms has fallen in Europe.”

US legislators may prove a stumbling block

The US President does not have the constitutional authority to sign off on trade talks alone: Congress would have to grant Obama “trade promotion authority”, which would then give Congress only the ability to approve or shoot down the overall deal, rather than the opportunity to amend it in ways that might upset sensitive EU interests.

In the US Opposition has been strong among US labor unions, as well as conservative Republican groups and more generally. Popular resistance to free trade and trade agreements is generally strongest in the US when economic times are bad.

The strong euro

This morning, Eurogroup president Jeroen Dijsselbloem acknowledged that some people think the euro is “too strong”, which Deutsche Bank thinks may come to impact on how favourable the negotiations seem to Europe:

The appreciation of the euro versus the dollar is also fuelling some political concerns over the timing of such an agreement, arguing that the EU would be opening its doors to US products at a time when European competitiveness is challenged.Relative energy prices are also being brought into the discussion. As energy costs in Europe are often rising (in Germany for instance), the US is likely to benefit from “fracking”.