How technology has doomed the BBC licence fee

WE SHOULD expect to hear much more about the future of the BBC in the next few months. Its Royal Charter is due for renewal in 2016, and there have already been murmurings about the sustainability of the licence fee model.

Last year, Conservative party chairman Grant Shapps suggested the BBC needed to clean up its act after the Jimmy Savile affair and concerns about executive payoffs, or risk the licence fee being taken away. Others have called for different TV stations to be allowed to compete for the guaranteed revenues. But last weekend saw the BBC’s director general Tony Hall launch a passionate defence of the licence fee – calling for it to be expanded to cover viewers watching on the BBC iPlayer service.

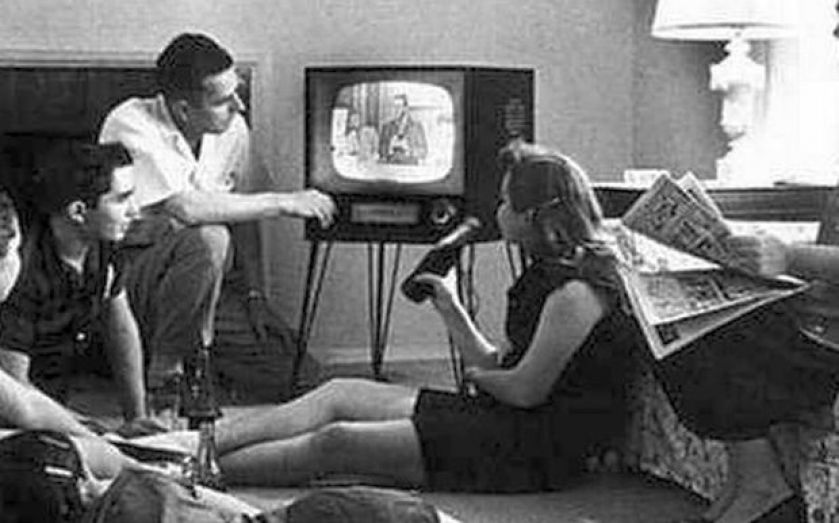

Hall is right to be worried about the disruptive effects of technology on the model, which was always supposed to be a charge linked to TV use. When it was introduced, there was a strong ideological aversion by the Attlee government to advertising, which was seen as evidence of the worst excesses of capitalism. Having ruled out this option, an annual tax-like TV licence made sense. TV broadcasting had the features of what economists then called a public good – it was non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Since signals were transmitted free-to-air via masts, one person watching the BBC didn’t affect the ability of others to do so. And it was hard to prevent someone from tuning in. So it made sense to create a separate funding stream to preserve BBC independence, while guaranteeing revenues for the state-owned monopoly.

Since then, of course, everything has changed. The existence of commercial rivals shows that pay-per-view, advertising and subscription are viable alternative funding models. But it’s technology that is really exposing the licence fee as untenable. TVs are not the only way to watch television. The iPlayer service, like its commercial equivalents, allows us to catch-up with programmes online. While you are prompted to say you have a TV licence when trying to watch live, extending it to cover all tablets, phones and computers would require authorities to be able to judge the ability of each to enjoy adequate signal coverage. As economist Tim Congdon has pointed out, it would be mad for a country trying to embrace the digital revolution to impose a new tax on all of these machines.

So if these options are unfeasible, what did Hall really mean when he said the licence fee should cover on-demand BBC iPlayer content? Presumably, he meant that you might have to log into iPlayer using a TV licence number or register a computer to view. In which case, he is arguing for a form of sign-up for online content. The logic of his argument is that the charge should not be linked to a TV, but instead to the ability to view BBC content per se.

Why not extend that principle? Instead of prosecuting people for non-payment of the TV licence, why not use the technology of digital decoders to block viewing of BBC content? Why should you have to pay if you don’t want to watch BBC content? In other words, why not make the BBC a subscription service like some of its commercial rivals, allowing people to view material only after paying for it?

The BBC licensing model is a privilege which exists to the detriment of its competitors and the free choices of consumers. The 2016 Charter provides an opportunity to fundamentally re-think this anachronism.

Ryan Bourne is head of public policy at the Institute of Economic Affairs.