Poorest areas in England hit hardest by tobacco taxes

There continues to be a strong link between smoking rates and economic deprivation, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

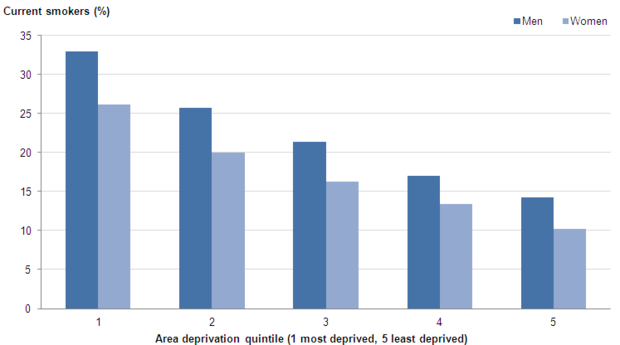

Smoking rates are disproportionately concentrated in areas of high deprivation, while more affluent areas tend to have lower smoking rates.

The ONS grouped areas of England into five categories (quintiles), with quintile one representing the most deprived areas in England and quintile five representing the most affluent.

Men in the most deprived quintile were more than twice as likely to smoke, compared with men in the least deprived areas. Smoking rates amongst women were also higher in the most deprived areas, with 26 per cent women from the poorest areas smoking compared to 10 per cent from the richest.

The figures may heighten fears that it is the poorest who are bearing the brunt of the ever escalating duty on tobacco.

Last year, the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) published a report highlighting the disproportionate impact that sin taxes, such as tobacco taxes, have on the less advantaged.

It was not always the case that smoking was concentrated among the poorest parts of the population. In 1977, the bottom quintile of the income distribution spent less on tobacco taxes than any other group, while the richest spent double that amount.

The UK has an especially punitive tax rate on cigarettes by international standards, with a typical pack of 20 cigarettes costs £7.98, of which £6.17 is duty and VAT. This amounts to a staggering 77 per cent of the retail price.

The uneven distribution of the costs of tobacco taxes can also be seen in professions. Those who work in routine occupations are three times as likely to smoke than those in upper management.

Author of the report Christopher Snowdon observes:

Put simply, the less money someone has, the more likely they are to buy the most heavily taxed product in Britain. Possible reasons for this counterintuitive correlation include the fact that financially stressed smokers are less likely to quit (Martire et al., 2011) and well-educated people are less likely to start (Hersch, 2000).

There is a strong chance that this trend is set to continue for some time, with 68 per cent of smokers in the top occupations saying they would like to ‘give up smoking altogether’ compared with 59 per cent of those in routine and manual jobs.