Real wages may rise, but earnings are still set for a lost decade

This morning’s official figures confirmed another drop in inflation, with consumer prices rising by only 1.6 per cent in the year to February, the lowest in four and a half years.

Average weekly earnings rose 1.7 per cent in the year to January, with private sector earnings up 1.9 per cent, and even stronger growth in sectors like, manufacturing and construction. We won’t know for sure until February’s labour market figures are released tomorrow, but it appears that a long period of declining real wages is coming to a modest end.

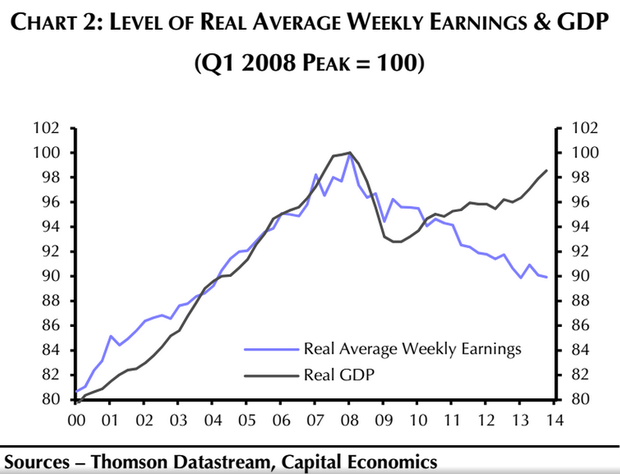

But that’s not really the full story. Though the direction of travel might now be changing, research from Capital Economics shows that the cumulative effect means real wages are at around 2004 levels – barring some kind of huge positive shock, there seems to be little chance of them returning to 2010 levels in time for next year’s general election.

So while the Labour party’s cost of living crisis line might look a lot weaker in the near future, there’s little chance that the average household will be able to say they feel better off than they were when the coalition government took over.

In fact, the report’s authors suggest that real earnings won’t return to pre-crash levels until 2020, with more than a lost decade in terms of wages.

This is partly because the rapid fall in unemployment has returned many lower-paid workers to the labour market, with lower-paid positions becoming more common.

There is a far larger proportion of employees earning the minimum wage, or very close to the minimum wage – though interestingly that does not appear to be a post-crisis trend. In 2001, around five per cent of employees earned within 50p of the minimum wage, up to early 11 per cent in 2012.

Capital Economics note that adult rate of the minimum wage, contrary perhaps to popular opinion, has been rising ahead of earnings growth in all but one of the years since the financial crisis, and is likely to continue to do so:

“The chancellor has suggested that he would like to see the legal minimum return to its pre-recession real level in the coming years (it is currently five per cent below its 2007 real-terms peak).”

The increasing share of low-paid workers means that increases in the minimum wage are likely to have more of an effect on earnings growth. However, it also means that any potential negative effects of raising minimum wages could apply to a much larger proportion of the workforce.