| Updated:

UK and European migration map: Why immigration is good for the economy and immigrants aren’t stealing British jobs

When outgoing European Commission president José Manuel Barroso accused David Cameron of potentially making a “historic mistake” with plans to call a referendum on the UK's membership of the European Union, he may have had a point.

Cameron has faced heavy criticism for his increasing focus on curbing immigration in response to Ukip’s growing popularity.

According to the Sunday Times, the Prime Minister is planning to cap the number of national insurance numbers issued to unskilled EU migrants.

But does the UK really need “regain control of our borders”, as suggested by Ukip?

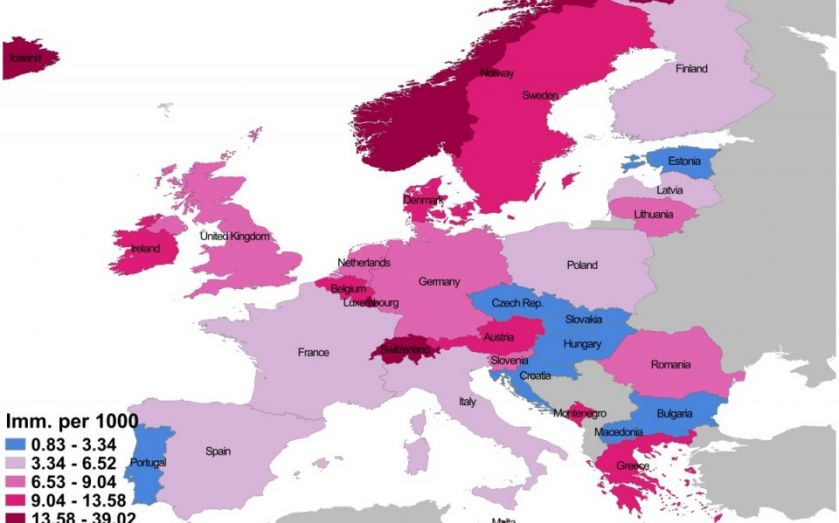

Immigration levels to the UK are high – but according to the most recent data available from Eurostat, it was only slightly above average in 2012.

Almost eight people in every 1,000 in the UK had immigrated that year – a total of 496,000 people.

Compared with the EU average of 3.4 immigrants per 1,000 people, that is quite high: a bigger rate than other major EU economies such as Germany (7.4), France (5.0) and Spain (6.5). However, there were over 10 countries in the EU with a higher number of immigrants per 1,000 people in 2012:

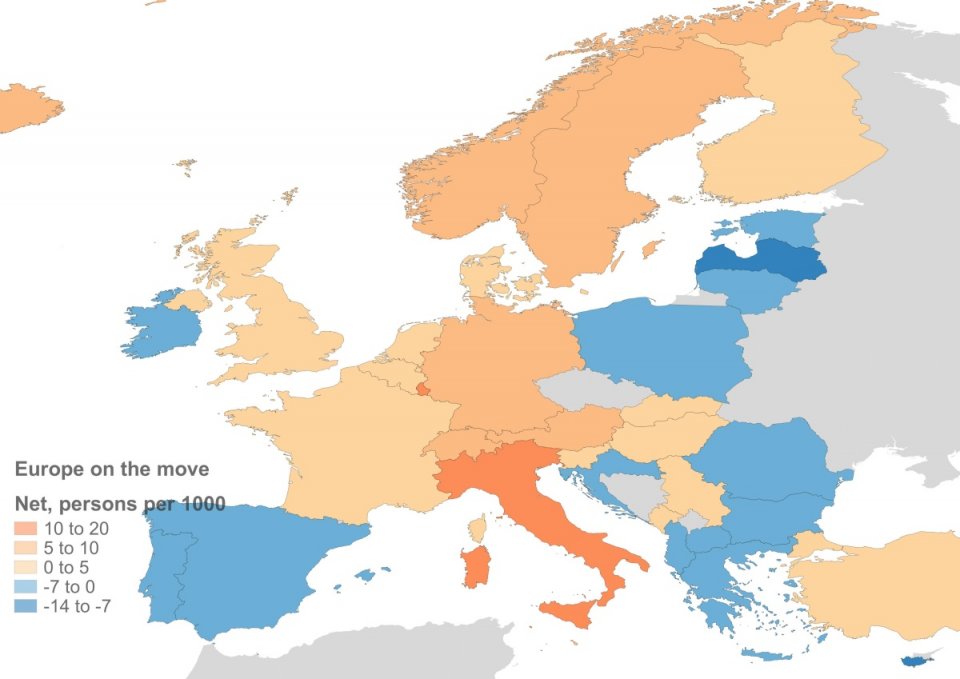

But to gain a clearer picture of migration levels, and what they mean for the UK economy, it's important to look at net immigration.

How high is the UK’s net migration?

Net migration or immigration is the result of the number of people leaving the country less the number of people coming in. Let's use the UK as an example: ONS figures estimate that during 2013, 530,000 people immigrated to the UK and 317,000 left (both on a long-term basis).

This means the UK has net immigration: the population is 212,000 greater because of immigration. The figures are rounded, which is why they don't seem to add up.

As the map below shows, some countries, such as Spain, are suffering net migration: more people are leaving than migrating to the country. In Spain's case this is because of a lack of job opportunities.

It's bad for the Spanish economy because it means educated youngsters are moving abroad to pay taxes in foreign countries and wasting the money Spain invested in their education.

The UK is also a big exporter of ex-pats, meaning net immigration is relatively low.

In the UK, according to Eurostat, 3.1 people (net) enter the country for every 1,000 people living here. That is below the EU average of 3.3, below the Eurozone average of 4.3 and below Germany’s rate of 5.8 persons.

Prosperous Nordic nations Sweden (6.9) and Norway (7.9) have higher rates too. France has a low rate (0.6 people per 1,000 members of the population) despite having high gross immigration. Spain has net migration – 5.5 people left in 2013 per 1,000.

All data in the map is from Eurostat, correct for 2013. Some rates are based on preliminary results or estimates.

Here are the 10 countries with the highest net immigration:

And the 10 with the highest net migration:

It may be argued that people moving abroad are often of retirement age and so are unlikely to be freeing up jobs as a direct result of their departures. Furthermore, ex-pats still receive state pensions and often winter fuel allowance but are spending that money in a foreign economy.

In the financial year 2012 -2013 for example, the government spent a total of £79.8bn on state pension payments, £2.2bn (in nominal terms) of which went to persons living overseas. £531m of that went to people living in Spain and £495m to people in Australia.

In 2011 -2012 £1.7bn was spent on winter fuel payments to Brits living abroad (this data isn’t broken down by country, but we can surmise from the pension data that a large proportion of ex-pats live in warmer climates).

Immigrants help the economy

Immigration is seen by many economists to be a positive: people coming from overseas tend to be better educated and younger, meaning they contribute more in taxes than they take out in benefits – 35 per cent more according to a study seen by The Economist.

Christian Dustmann and Tommaso Frattini, of the Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration, found European immigrants paid a staggering £2,610 more in taxes than they received in benefits each year between 2007 and 2011.

Surveys of business leaders have indicated EU workers tend to have skills and commitment that make them attractive to employers and good for the economy.

The data also supports foreign workers as contributing to the economy. According to data from the department of work and pensions:

As at February 2014, approximately 15 per cent of working age UK nationals were claiming a DWP working age benefit compared to 7 per cent of working age non-UK nationals (at the time they first registered for a National Insurance number [NINo]).

It goes on to say:

134,000 (11.7 per cent) of Jobseekers Allowance claimants are estimated to have been non-UK nationals when they first registered for a NINo. Of these, 48 per cent are from within the European Union.

That 11.7 per cent figure may sound high, but 15.6 per cent of the UK working age population is made up of non-UK nationals, so that’s proportionately better.

Here is a visualisation using data from the ONS showing net immigration. The uptick at the end partly comes because restrictions on Romanians and Bulgarians coming to the UK were lifted in January. Their contribution (28,000 in the year to March 2014, up from 12,000 the year before) to the total was labelled "statistically significant" by the ONS.

And it's worth noting that immigration has been this high before.