Japan’s perpetual QE machine: Could the exercise end in tears?

Some analysts think inflation at any cost is the wrong aim

THE WORLD’S third largest economy now has the same credit rating as Bermuda, Oman and the Czech Republic, after rating agency Moody’s downgraded Japan’s debt from “Aa3” to “A1” yesterday morning. The yen crashed against the dollar (dollar-yen topped ¥119 just after the announcement, its highest level since 2007, before reversing slightly), while Nikkei futures fell by 0.7 per cent in after-hours trading.

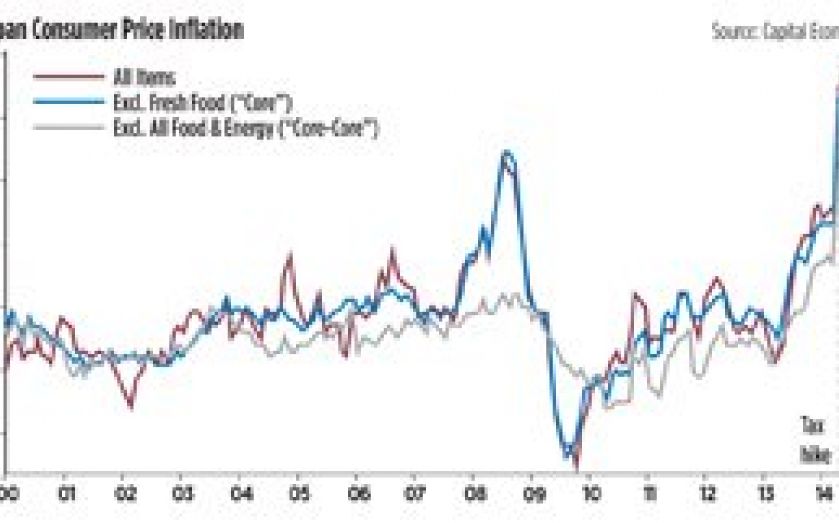

Japan’s main stock index has risen by almost 12 per cent since Bank of Japan (BoJ) governor Haruhiko Kuroda announced a new round of QE at the end of October (see graph). In that time, the country entered its third recession in the past four years, annual core consumer inflation figures indicated that inflation slowed for a third straight month in October, and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called a snap election for 14 December in order to consolidate the mandate for his three-pronged economic revival plan, dubbed Abenomics.

There are many who believe that the joint efforts of Abe and Kuroda may yet succeed in pushing inflation back up to the 2 per cent target, helping to spur a rebound in consumer spending and economic growth.

But others, notably Charles Dumas, Diana Choyleva and Freya Beamish of Lombard Street Research, argue that Japan may now be locked into a state of “perma-QE” – a kind of monetary perpetual motion machine that could see the BoJ buying government debt with no end in sight, sustaining government fiscal deficits. And endless debt monetisation, Beamish argued in a recent note, would be “a recipe for loss of faith in BoJ liabilities, causing a depreciation spiral that could end in financial crisis.”

THE CONFIDENCE TRICK

A popular view is that Japanese policymakers should be pursuing price rises at any cost. The country’s economy has suffered from years of subdued inflation, and most agree that convincing consumers that prices will consistently rise in the future is necessary for an uptick in spending and growth. The alternative is that firms and households continue to put off spending, anticipating disinflation and possibly a return to deflation.

The success of Abenomics, then, in large part comes down to the extent to which Abe and Kuroda can convince Japanese consumers that they’re committed to inflation for inflation’s sake – and the BoJ’s printing of money to buy government assets through QE is a key part of this. Many analysts, including Alan Higgins of Coutts, argue that this will be supportive of Japanese equities in the future, as well as helping to keep down the value of the yen. The BoJ’s latest intervention took the annual pace of its asset purchases to ¥80 trillion (£431bn), and Capital Economics expects this to be increased even more to around ¥90 trillion next year, as price rises stay low.

INFLATION VS INFLATION

The relentless pursuit of inflation as an end in itself, however, could be more problematic than most assume, Beamish and her colleagues have argued. Before the introduction of a sales tax hike in April, she writes, the central bank’s stimulus programme seemed to be doing a pretty good job of pushing up inflation rates in Japan. But much of the heavy lifting has been done by rising import costs as the value of the yen fell – this isn’t necessarily the type of inflation that will lead to sustainable, demand-led price rises in the future.

In the jargon, it’s “cost-push” inflation, rather than “demand-pull” inflation. And while it’s no doubt a boon for some sectors, Beamish says that it’s “been harmful to the economy overall.” Pushing up prices by depreciating the yen may cause households to bring forward some of their spending, but it reduces the real value of their incomes even further – and “the Japanese worker is significantly worse off than before the BoJ embarked on its new monetary policy,” Beamish’s note argues. Hardly a recipe for the kind of confidence Abe requires to pull off his inflation trick.

What of demand-led inflation? The initial consumption tax increase in April choked it off in its infancy, Lombard Street’s analysts have said, and it could therefore be seen as a positive that the next hike has been delayed.

But at the same time, as yesterday’s Moody’s downgrade highlighted, the government is under huge pressure to do something about its fiscal position. Net government debt is equal to around 134 per cent of GDP, and around 15.6 per cent of tax revenue goes to servicing the interest on this debt every year. Abe is caught between the need for significant fiscal consolidation and the necessity of getting prices rising again. Beamish’s note argues for a two-pronged approach, removing supply-side blockages in labour and capital markets and adjusting fiscal policy to suit an ageing population. Instead, despite the new mandate Abe should receive in this month’s election, we’re likely to see continued fiscal deficits sustained by QE, rather than a serious stab at structural reform.

QE ENDLESS

As economist Noah Smith of Stony Brook University argued in a recent piece for Bloomberg, the monetisation of public debt through further BoJ government bond purchases seems to be the most likely option. In doing this, the central bank is effectively able to keep yields low and stimulate inflation at the same time, using the yen to buy government debt. It sounds alluring, but where would QE in perpetuity leave Japan?

It could get very ugly, argues Beamish. The BoJ stimulus machine can sustain itself by effectively printing yen to buy government debt. But if it succeeds in creating 2 per cent inflation, the government will then be faced with a rise in borrowing costs as the BoJ starts to taper its asset purchases. Worse, the central bank is effectively “debasing the yen” in this scenario, says Beamish.

The danger is that Japan becomes locked into a cycle of ever more QE, until investors one day decide that they “don’t want to hold a currency issued by a central bank that is obliged to keep printing more of it until there is nothing left to buy.”