The web on film: As Modern Family sets an episode on a laptop, what are the problems with filming the net?

You’re having dinner with an old friend. The conversation flows until his phone, which has been sitting on the table beside his plate, vibrates. He looks down, but continues to nod as if still engaged in the conversation.

“Yeah,” he says, scrolling to the bottom of the message, eyes widening at some surprising detail.

“I’ve been hearing voices.”

“Yeah…” still looking at the phone.

“I’ve got ebola.”

“Mmm,” still looking at the phone.

“Look that man has a gun.”

“Okay.”

Macho typing in Blackhat, released this week

Given how annoying this scenario is in real life, perhaps it’s unsurprising that film-makers have found it hard to depict it in a captivating way on screen. From Michael Mann (this week’s Blackhat) to Kenneth Branagh (Jack Ryan), even the best directors have struggled to make people staring into screens look anything other than crushingly dull.

For all its dizzying chaos, the world of social media essentially consists of millions of people sitting, typing and clicking – hardly the most filmic of activities. For a long time directors were reluctant to go there at all. It’s been almost a decade since Twitter and Facebook started changing how we interact, but only recently have we seen a glut of movies with plots that turn on a social media related controversy (Chef, Sex Tape, and Men, Women and Children to name a few).

The Social Network

Social media is no longer something film-makers can afford to ignore. People fall in love, have sex and break up on the internet. It’s a place where people meet friends, make millions and take down governments. Screens play an intermediary role in most of the dramas of modern life and this is something film-makers have to reflect if they want to say anything relevant.

Pre-internet, directors made computers appealing with cool bleepy noises and pages of flickering numbers, but these days anything that deviates from a familiar Windows or Apple interface tends to look unrealistic. So how do you depict modern computers?

Two ways stand out. First there’s the old trope where characters type loudly into a keyboard and wait, brow furrowed, for a loading bar to complete or a page to fill with search results. This has been going on since Goldeneye and was a prominent feature of that landmark internet film, the Social Network. It’s a cliché that many films find difficult to avoid.

The start of a Twitter storm in Chef

More recently, with the rise of smartphones, directors have started putting messages in animated letters on the screen (see Liam Neeson above). Well-meaning food-porn comedy Chef did this, as did the significantly less successful Liam Neeson vehicle, Non-Stop. This method allows actors to move around instead of just reading statically, but it can be an anti-naturalist distraction – in a film like Chef, which concerns a midlife crisis, divorce and single-parenthood, ideally you wouldn’t have a little animated blue bird popping up every five minutes to signify the arrival of a tweet.

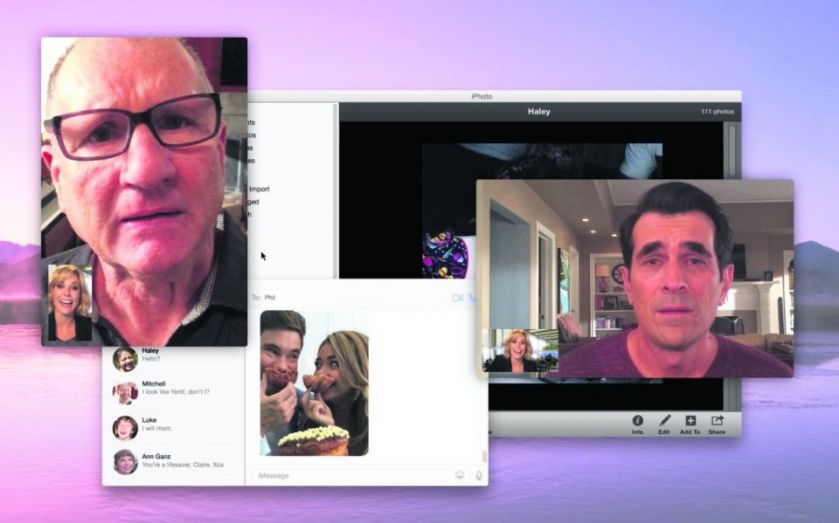

The world of TV is leaving the movie world in the dust when it comes to thinking of innovative ways to depict our internet-filled lives. Next week, an entire episode of ABC’s award-winning comedy Modern Family is going to be set on Claire’s laptop. She instant messages, converses over Skype and sends video links sent to friends. The episode, called “Connection Lost”, may seem gimmicky, but in showing us exactly what Claire is seeing, it eliminates feeling of alienation that inevitably accompanies watching a human watch a machine. Modern Family’s experiment follows Lena Dunham’s expert use of Facetime in the season two finale of Girls, in which Adam ran to Hannah’s rescue while reassuring her via videophone.

Liam Neeson in Non-Stop

There are, however, pitfalls involved in giving technology such a prominent role. If there’s one thing that makes a film look dated – even more than fashion and dodgy special effects – it’s technology. From the Myspace-based plot of He’s Just Not That Into You to the phonebooth in, er, Phonebooth, even relatively recent movies can be made to look absurdly out of time.

Still, as technology proliferates into every corner of our lives, film-makers have no choice but to follow suit.