Creativity makes a vast contribution to business: We ignore it at our peril

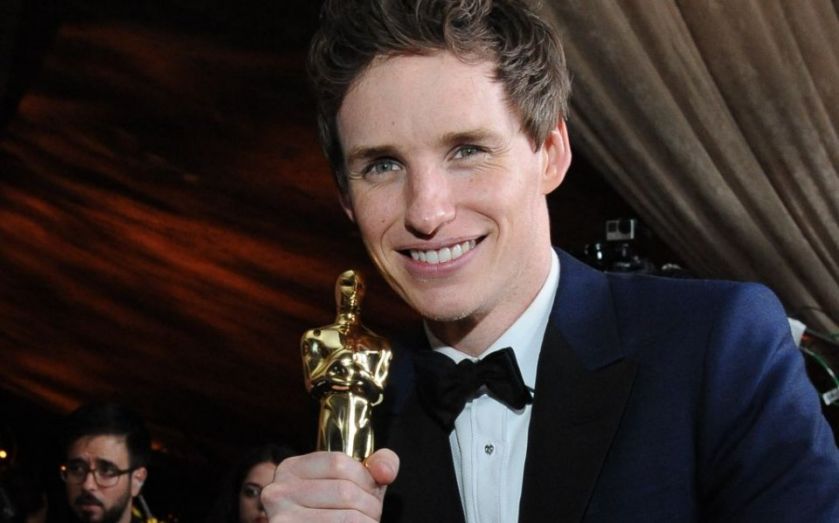

The Academy Awards have become a (not especially accurate) measure of the UK’s cultural standing in the world. Thanks to Eddie and co, the Brits officially had a good Oscars, with four wins from nearly 40 nominations, but we need not obsess over the results of this dubious annual assessment. Our film stars are just the glittering tip of a giant iceberg of British creativity.

The iceberg is formed from a range of sectors straddling the arts and business, which New Labour gathered together in 1997 and styled as “the creative industries”. They include music, tech, TV and film, publishing, gaming, architecture, design and advertising.

The label was misleading (creativity of one form or another is essential for all successful businesses, from fashion design to engineering, pharmaceuticals and even finance), but useful nonetheless.

It was long-overdue recognition of the important economic contribution made by sectors often dismissed as being lightweight and populated exclusively by luvvies. It also gave weight to the UK’s claim to be a world leader in the space “where culture meets commerce.”

Official government statistics show that the creative industries were worth £76.9bn to the UK economy in 2013 – up 10 per cent on 2012. No other industry grew as fast.

The sector accounts for more than 5 per cent of all British jobs, and nearly 9 per cent of UK service exports.

The coalition government picked up where Labour left off, and has worked with business on a strategy to support and continue to grow the creative industries.

Concerns remain over education policy. As crucial as it is to promote the STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths), and to bring code into the classroom, it would not be wise – either from a cultural or economic perspective – to marginalise arts-related subjects in the process.

According to reports from the Creative Industries Council and, more recently, the Warwick Commission, this is exactly what is happening.

Ultimately, though, the onus must be on organisations themselves, especially in the absolutely critical area of talent. Nowhere is this more true than in advertising and marketing services, the definition of a people business. At WPP we invest more than £8bn a year in human capital. Finding and developing talented people is fundamental to our success.

One exceptionally talented Brit who has also tasted success at the Academy Awards is Sir Alan Parker. Before he started collecting Oscars, Golden Globes and Baftas, his mantelpiece was filled with yellow pencils.

A pencil from D&AD (Design and Art Direction: the charity and awards organisation that celebrates commercial creativity) is one of the ad industry’s greatest accolades. As a top copywriter and director of TV commercials in Sixties and Seventies London, Parker won a lot of them.

He also served as president of D&AD, which has been a great champion of education within the industry, and works very hard to bring young people into it. The D&AD New Blood Academy, which WPP supports through a partnership led by our worldwide creative director John O’Keeffe, is one example. Aspiring creatives compete for a place on the Academy bootcamp, which in turn offers the chance to win paid internships with WPP agencies.

There are others. The School of Communication Arts, for instance, is a social enterprise created by the advertising industry to offer an alternative to the traditional education model, supported by more than 100 agencies.

Such initiatives are vital for our sector, but a greater focus on the value of applied creativity is important for the wider world of business, and the economy as a whole.

Recently, some of the world’s leading business brains have gone out of their way to highlight the role of more intuitive, subjective, creative thinking in driving corporate performance, and to warn that an excessive boardroom focus on number-crunching and cost management is coming at the expense of experimentation, innovation and top-line growth.

In this fearful, post-Lehman age, finance directors, accountants and procurement officers have a great deal of power. Harvard Business School’s Clay Christensen estimates that up to 90 per cent of managers’ time is spent on “the assembly of numbers,” with the result that change is only ever incremental.

Roger Martin from the Rotman School of Management reminds us of the need to appreciate “qualities, not just quantities,” and to stop basing all forward-looking decisions on the forensic analysis of past data.

Chief executives (especially former finance directors like me) should take note: it’s hard to imagine the future when your head is buried in a spreadsheet. And there are no gongs for businesses without a long-term plan for growth.