The end of growth? Why the techno-optimists could be wrong about a coming golden age of innovation

A new book by the economist Robert J Gordon – The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The US Standard of Living since the Civil War – is causing quite a stir.

His essential message is that future growth will be much slower than in the past, due to two broad arguments. First, the Third Industrial Revolution (general purpose technologies in IT and communications) won’t have the impact of previous general purpose technologies, such as the invention of electricity and motor vehicles. Second, the US economy faces other significant headwinds over the coming decades (the impact of rising inequality, reduced educational attainment, an ageing population and baby boomer retirement, the expansion in public debt, and breakdowns in family structure), which will further reduce growth.

Gordon argues that the gains from IT and communications have been largely seen already, in the acceleration in productivity over the 1994-2004 period, and that they are essentially transient, as evidenced by the slowdown in productivity growth after this period. In other words, the low hanging fruit have already been eaten.

He concludes that, “when all the headwinds are taken into account, the future growth of real median disposable income per person will be barely positive and far below the rate enjoyed by generations of Americans dating back to the nineteenth century… [there is] virtually no room for growth over the next 25 years in median disposable real income per person.”

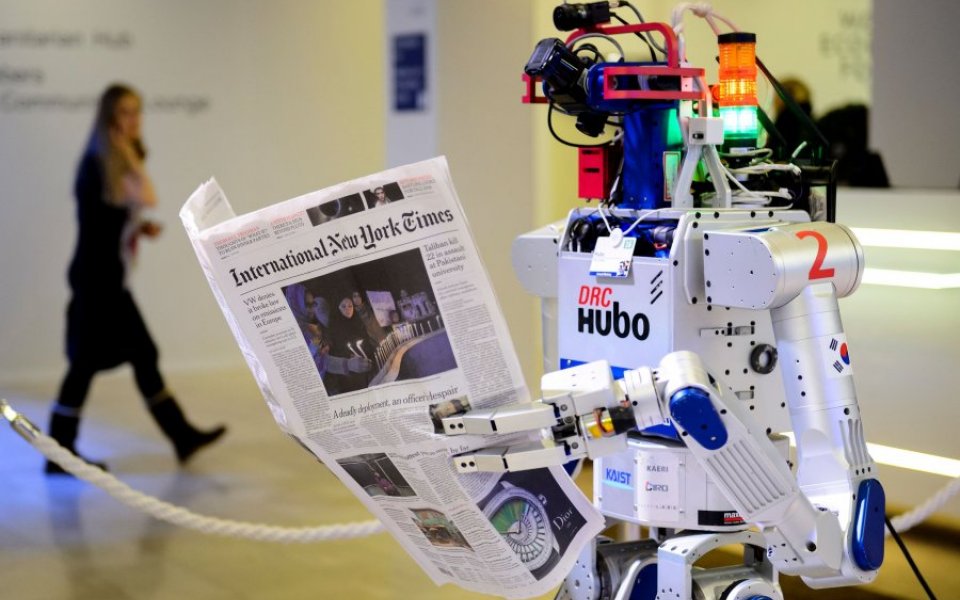

But Gordon’s message clearly conflicts with the so-called techno-optimists who see us as being in the foothills of a new golden age of economic performance, led by the widespread adoption of artificial intelligence, robotics, 3D printing, driverless cars and nano technology. The techno-optimists see considerable employment downsizing, and a surge in productivity, as men are replaced with machines (also creating employment in the sectors producing the new kit). Gordon instead sees a huge disjuncture between the techno-optimist narrative and the productivity statistics.

Will innovation turn back upwards? Will the lagged effects of the latest general purpose technologies kick-in a second time? These are very difficult questions to answer with any certainty. But ultimately they will determine whether or not the Gordon thesis is proven correct.

Gordon cites six measures suggesting a slowdown since the dot-com decade (1994-2004). But these measures are not comprehensive. Others could be cited suggesting a different perspective. Different measures, and the fact that the period from the mid-00s onwards has coincided with the Great Recession, further muddy the waters. So the battle lines are drawn. A future of spectacularly faster productivity growth, built on an exponential increase in the impact of artificial intelligence, squares up to total factor productivity growth since the mid-00s of just 0.5 per cent per annum. The techno-optimists see us going back to the future, in a 1950s-revisited scenario, when total factor productivity growth averaged almost 3.5 per cent per annum.

Fortunes will be won and lost by people deciding which side of the fence, in this debate, they sit on. At the moment I’m stuck on the fence!

One final thought. As Lawrence Summers has pointed out, stagnating incomes do not mean that people don’t become better off over the course of the life cycle. Incomes rise as people progress in their careers. Gordon’s argument simply means that the next generation of workers will not be much better off, if at all, compared with the current incumbents in these roles.