US election shows voters care more about inflation than growth

Donald Trump’s re-election as President has raised fundamental questions for Labour’s economic and political agenda.

Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have repeatedly argued that economic growth lies at the heart of their policy agenda. Kickstarting growth, they argue, is necessary if living standards are to rise and public services are to improve.

Labour’s plan to lift growth has a clear inspiration. Reeves has frequently expressed her admiration for Joe Biden’s economic policies, embodied in legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act. These are examples of ‘modern supply-side’ policies in practices.

And Reeves is not the only one looking across the Atlantic for inspiration. The recent Draghi report on European competitiveness was littered with comparisons to the US. Indeed the whole document was an attempt to understand why the European economy has struggled to match US dynamism.

It’s easy to see why Europeans have been looking enviously at Biden’s economic boom. Joe Biden’s America has been by far the fastest growing major economy in the world since the pandemic.

At the midway point of this year, the US economy was 10.7 per cent larger than it was pre-pandemic, way ahead of its nearest G7 rival.

Many analysts have argued that the US’s striking performance has been a direct result of Biden’s stimulus measures following the pandemic.

The US government provided far more generous financial support to households than elsewhere in the G7, ensuring the economy essentially never suffered from an output gap.

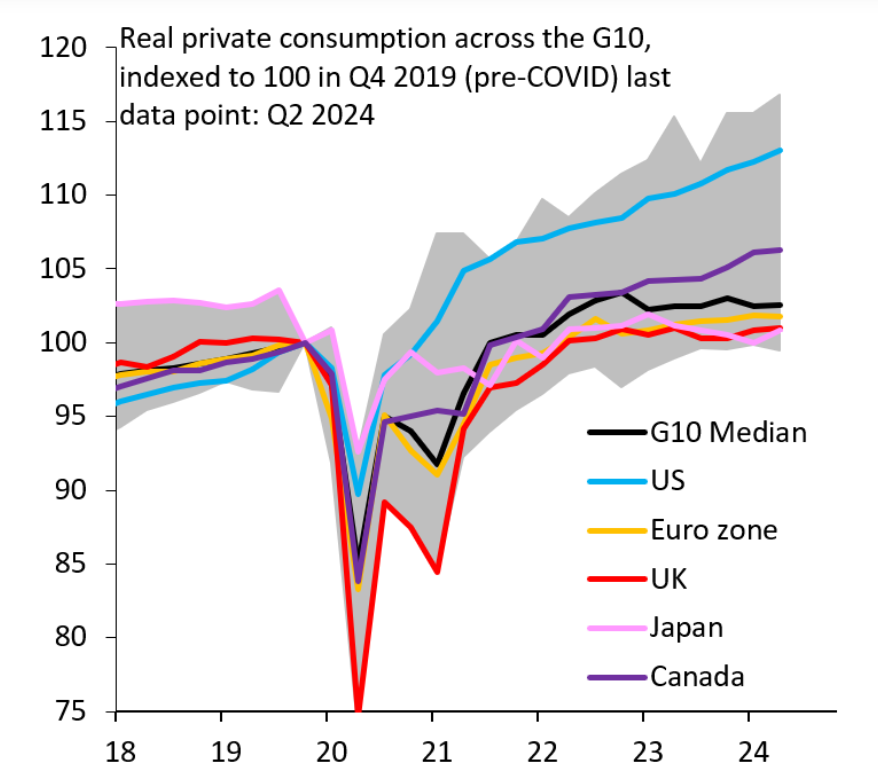

Analysts at the Brookings Institute, a US think tank, showed that private consumption in the US grew at a much faster rate than elsewhere in the G10 due to Biden’s fiscal largesse.

“This support in the US was far more generous compared to the rest of the G10 and—as a result—the US has now meaningfully outperformed its peers,” Robin Brooks and Ben Harris, both from the Brookings Institute, said in a paper.

Businesses investment has also expanded at a much faster pace than elsewhere. US investment is 14 per cent above its pre-Covid level while investment in the eurozone was seven per cent below.

Again, there’s a strong case that this is a direct result of the generous incentives included as part of measures like the Inflation Reduction Act.

So why did the Democrats lose?

On the face of it then, Biden’s economic success was unparalleled across advanced economies. And yet voters decisively rejected his policies in last week’s election.

This could be a real problem for Labour. Much of their agenda is premised on making unpopular decisions in order to kickstart growth. The prime example is planning reform.

Their hope is that stronger economic growth will counterbalance the initially unpopular decisions.

But if voters do not feel the benefits of stronger growth, then ‘unpopular decisions’ are hardly going to make a good pitch for re-election.

There is, of course, a much more obvious culprit for the Democrats’ defeat: inflation.

In the exit poll nearly 80 per cent of Republican voters said the ‘economy’ was their most important concern. Clearly they weren’t talking about the US’s world-beating growth or the historically low rate of unemployment.

Leaving aside debates about whether inflation was transitory or the extent of Biden’s culpability, there is no denying the simple fact that inflation hit its highest level since the 1970s in 2022.

Biden is not alone. Incumbents all over the world suffered a bruising year in 2024, seemingly irrespective of the performance of the economy.

Apparently voters dislike inflation more than they like growth.

This should be a cautionary note for Reeves. Economic forecasts from the Bank of England and the OBR suggest that Labour’s Budget will force up inflation alongside stronger growth.

According to projections forecasts, inflation will peak somewhere around 2.8 per cent next year.

Clearly this is not a big increase relative to the scale of the inflationary surge a few years ago. Andrew Bailey himself said the Bank’s rate outlook was largely unchanged.

But still, the lesson of 2024 is voters really don’t like inflation.