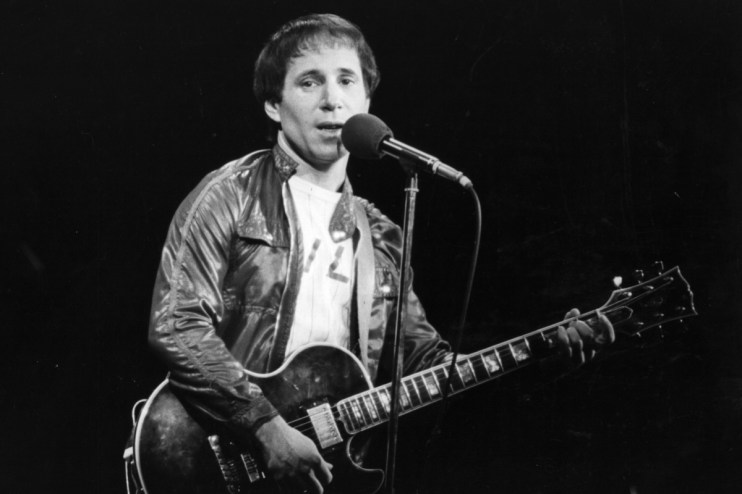

Strange dreams: Lessons from the life of Paul Simon

An essay on what I have absorbed over a lifetime listening to Paul Simon

What do you need to make a musical career? I’d say it comes down to one thing: a talent for immediacy. If you don’t have it, the chances are you’ll lose out to someone who does. I remember when I first listened to ‘The Sound of Silence’ in that wonderful Dustin Hoffman film The Graduate (1967): I was only 15 and as blank a listening canvas as can be imagined. But the effect was immediate: that day I went down to the old record store in Godalming and bought Simon and Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits.

I’ve been listening to Paul Simon on and off ever since, so much so that it is hard to imagine my life without his consoling voice, his cunning lyrics, and his explorations of international rhythm. Now, with Seven Psalms released in 2023, and the two-part documentary In Restless Dreams released the same year – and updates regarding his Beethoven-esque hearing loss in one ear following in 2024 – we have an opportunity to consider the last act of Simon’s career.

Paul Simon’s late works

Late works are a subject of perennial interest. Something seems to happen when the grave nears: there can be a sharpening of perception, and a sense even of the material veil about to be lifted. In literature, Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1610-11) with its world of fairies and valedictions is perhaps the most notable example of a viewpoint shifting as this world’s impermanence becomes increasingly evident to the writer. In poetry the famous lines by WB Yeats in the poem ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ might be taken as a sort of mantra for the ageing artist:

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress…

That is what Simon is doing in Seven Psalms – singing for every tatter in his mortal dress. In music, the most obvious touchstone is those great late string quartets by Beethoven, where we feel the composer to be inhabiting a sort of ethereality. What appears to happen as mortality rears up is that the artist feels a heightened sense of the beauty of things and the fragility of the life they are about to leave. At the same time, we sometimes find the shape of intuitions about what may or may not come next, and Seven Psalms is a little like this.

The album comes up on Spotify and Apple Music as one long track 33 minutes long, but it also consists of seven interconnected tracks beginning with ‘The Lord’. Every track feels wispy and valedictory – like someone taking a last look around a house which they have just sold and are about to vacate for the last time.

But throughout, a certain confidence underpins it and somehow or other, as shown by the title of the album, this seems to have to do with some sort of faith. This is a little unexpected since it isn’t something which Simon has spoken about much in his highly secular career, and in fact he has stated in interview that he isn’t religious at all.

All one can say to this is that any cursory listen of this album makes you think he’s doing an excellent impression otherwise. In fact, the powerful nature of the testament Simon is giving us here makes one wonder whether it’s possible to be religious without knowing it – indeed perhaps it’s a far more common condition than we realise. Here’s a sample lyric from the opening track ‘The Lord’:

I’ve been thinking about the great migration

Noon and night they leave the flock

And I imagine their destination

Meadow grass, jagged rock

The Lord is my engineer

The Lord is the earth I ride on

The Lord is the face in the atmosphere

The path I slip and I slide on

This is the language of the metaphysical poets, and is as religious as it gets. Even more interestingly, Simon has stated in interview that the idea for the album came to him in a vivid dream, where he received this clear instruction: “You are writing a piece called Seven Psalms”. Simon woke up in the middle of the night and wrote the title down at a time when he claims he didn’t even know what the word ‘psalms’ meant. This is odd since it’s quite a common word which one might expect an educated octogenarian to know about. Not since Paul McCartney woke up humming ‘Yesterday’ has music emanated so definitely from dream like this.

Playing the language of metaphysics

It sometimes feels as though this album therefore has some sort of special validity; it is certainly quite different from all his other albums. In ‘The Lord’ Simon continues:

And the Lord is a virgin forest

The Lord is a forest ranger

The Lord is a meal for the poorest

A welcome door to the stranger

The Covid virus is the Lord

The Lord is the ocean rising

The Lord is a terrible swift sword

A simple truth surviving

This achieves the sort of compression and reach which isn’t usually to be found in Simon’s songs – nor is it to be found generally in pop songs full stop. Here compression is allied to a sort of visionary certainty about the nature of divinity which may indeed have come through Simon, as an inspiration quite separate from the Paul Simon who presumably goes about his daily life.

But there’s more. It turns out that the whole album was written by dream prompts. In the CBC interview he continues:

Maybe three times a week, I would wake up between the hour of 3 a.m. and 5 a.m. with words coming, and I would just write them down…If I used my experience as a songwriter, it didn’t work. And I just went back into this passive state where I said, well, it’s just one of those things where words [were] flowing through me, and I’m just taking dictation. That’s happened to me in the past, but not to this degree.… I’ve dreamed things in the past — I didn’t necessarily think that they were worth noting. That’s why it’s unusual that I got up and wrote that down.

Simon, then, appears to have entered into some process of communication with the psychological process which makes dreams: since this process also occurs in the wider universe and is impossible to divorce from it, we can say that he was also in some form of cosmological engagement which was wholly unusual for him. It was a reckoning of sorts – and one also that was presumably occurring, since people don’t live much longer than 80, fairly near to death. All in all, one cannot help but feel that this album amounted to a new kind of creative opportunity presented to Simon – and without being morbid, a last ditch one at that.

We can further guess that this new sort of creativity may have been linked to some sense of inadequacy at all that he had achieved up until that point in his career. In the quote above he references how his previous songwriting practice felt irrelevant to this new project: I would guess that this is the manifestation of a certain dissatisfaction with the way in which he has gone about his creative life, no matter how successful and laurelled he is.

Perhaps, despite his enormous achievements, there could even be said to be a certain justice about that verdict which, depending on how we view the meaning of dreams, was coming through him, or from him. As odd an admission as it may be for the person who wrote ‘The Boxer’, Simon has sometimes in interview expressed a sense that he is somehow in the second tier. In particular, he has always come in second to Bob Dylan. In 2011, Simon told Rolling Stone:

I usually come in second to Dylan, and I don’t like coming in second. In the beginning, when we were first signed to Columbia, I really admired Dylan’s work. ‘The Sound of Silence’ wouldn’t have been written if it weren’t for Dylan. But I left that feeling around The Graduate and ‘Mrs Robinson’. They [my songs] weren’t folky any more.

And why was Simon always runner-up like this? Simon continues:

One of my deficiencies is my voice sounds sincere. I’ve tried to sound ironic. I don’t. I can’t. Dylan, everything he sings has two meanings. He’s telling you the truth and making fun of you at the same time. I sound sincere every time.

The difference from Dylan

This is worth unpacking. The truth is that Dylan came to songwriting almost weirdly fully formed. There was a specific reason for this: that he was drawing from the past, and often, frankly, copying it. That’s why there’s no juvenilia by Dylan: he comes straight out of the gate with ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ and ‘Girl from the North Country’. These songs are sponsored by, it can sometimes seem, a great chorus of American experience.

Well, if you’re travelin’ in the north country fair

Where the winds hit heavy on the borderline

Remember me to one who lives there

She once was a true love of mine

‘Winds hit heavy on the borderline’ is excellent, but the song has both a fresh and ancient sound – and Dylan had the voice to convey those ideas simultaneously. The same was never true of Simon’s early work. We might take ‘Homeward Bound’ as an example:

And all my words come back to me

In shades of mediocrity

Blank emptiness and harmony

I need someone to comfort me.

This amounts to an immature complaint about life on the road which Dylan would never have permitted himself. It is part of that unlovely genre: rich rock stars moaning about having to be away from home a bit to make their money. These deficiencies – though they are offset in ‘Homeward Bound’ by some nice chord changes, particularly in the verses – appear to have stayed with Simon throughout his life.

There is a story of Simon playing a gig in Greenwich Village in the early 1960s, and noticing when up on stage that Dylan was sniggering about his performance with his own future biographer Robert Shelton. I’ve never been sure about the truth of that story, although Dylan could undoubtedly be harsh. Is it not more likely that they were laughing about something else?

In fact, whether it happened precisely that way or not, the story touches on Simon’s insecurity in relation to Dylan: what really matters is that he thought Dylan was laughing at him whether he was or not. Why might Simon feel this way? It’s because he knows his inadequacy in relation to Dylan.

Like a Rolling Stone

Simon states in the Rolling Stone interview that this inferiority has to do with Dylan’s ability to apply layers of meaning not just in his lyrics, but to his vocal delivery. Simon is being hard on himself – as all artists need to be, provided that self-criticism doesn’t stymie creativity. But there is nevertheless truth to his verdict, and it is useful to have Simon articulate so clearly the central mystery of what makes Dylan uniquely compelling.

How does Dylan achieve it? It is very difficult to say but my own sense is that Dylan’s immersion in the past – and really in life generally – has been so deep that he has come out so entirely soaked in art and experience that his singing is never entirely for himself. His experience is multifarious: he is many. His art can at times seem to have almost nothing to do with him. One never feels that there is any stability in the word ‘I’ in Dylan’s songs: nothing can ever be traced reliably back to him.

The same isn’t true of Simon: in his songs, even the very best of them, there’s always a slight air of solipsism amid all the lovely melodies and the beautiful ideas. He is writing in order to unburden himself; Dylan is doing nothing less than carving out, or reimagining, nationhood in song.

There are many ways in which this smaller tendency can illustrate itself in Simon’s career. The principle one is in being too clever. This exists across his canon. It is there in the Joe DiMaggio line in ‘Mrs Robinson’ which is probably too arbitrary; when Dylan namechecks people it is always as a way of going back to some definite idea, emotion, or set of principles, as in his great song ‘Blind Willie McTell’. Furthermore, this is a deficiency which Simon is aware of. There is also video footage in the 1990s of Paul Simon listening back to his magnificent song ‘Graceland’. He is being filmed listening to the words:

And my travelling companions

Are ghosts and empty sockets

I’m looking at ghosts and empties.

Listening back to this, his facial features twist with regret: “Too many words,” he says, genuinely berating himself. “Too many words”.

He is right. And too many words is always a symptom of trying too hard which in turn is to do with lack of self-confidence. By contrast, we might note how the whole magnificent universe of Dylan’s “Mr Tambourine Man” unfolds effortlessly, without any ambition intervening.

Dylan has superior knowledge about the world, which is really another way of saying that he understands himself better. Incidentally, Simon never wrote a line as good as: “I know that evening’s empire has returned into sand,” which shows a true poet’s innate perception of evenings – not to mention of empires and sand. I’m not sure Simon is ever seeing things so clearly as this; his ego, in the shape of his cleverness, keeps coming in between him and the thing he is trying to describe.

This lack of self-confidence in Simon might have to do with an absence of historical roots. This was, to put it mildly, never the case with Dylan who has travelled the world on his Neverending Tour, but always as an American mining his Americanness. Lack of a real centre meant that Simon went journeying, first to South Africa to record his best solo album Graceland (1986) and then to Brazil to record his second best Rhythm of the Saints (1990).

Considering Graceland

These albums were made in a completely different way – one might say that they have to do with avoidance regarding the core reasons for a restlessness which Simon has always felt. He recorded the rhythm track first and then recorded the melodies over the top. It was a fascinating exploration of another country, and produced some songs which border on being standards: ‘Boy in the Bubble’, ‘Graceland’ itself, ‘Diamonds on the Soles of Their Shoes’, although it might be that ‘You Can Call Me Al’ is marred by some slightly silly lyrics.

But the only real limit on the Graceland album is tied to its core concept: the lyrics feel like journalism, and make one think of Sir Tom Stoppard’s joke in his 1978 play Night and Day, that a foreign correspondent is “someone who flies around from hotel to hotel and thinks the most interesting thing about any story is the fact that he has arrived to cover it.”

Something like this appears to apply to Graceland and Rhythm of the Saints. There is a shallowness to his observations about poverty in South Africa for the very simple reason that Simon doesn’t live there, and can’t really know what’s going on. Damon Albarn faced a similar problem when he came to make his album of Mali Music.

Surrealism in Simon has its limits too. In Dylan’s surrealism – especially in Blonde on Blonde – we experience the excitement of the poet’s discovery of Baudelaire and Rimbaud. It is probably true to say that Dylan doesn’t always make definite sense, but there is something vast and brave about the exploration being undertaken; and very often one senses a large world of meaning bordering the difficulty of the language – a world of dream-like correspondences. But in Simon surreal language too often goes in the direction of archness.

Lyricists mustn’t let the listener know that they’re clever; what needs to be communicated instead is that they love truth, and then that they love language – and in that order. At the highest peaks of the Dylan songbook these two are in the right order – and of course, married to the music. With Simon, something is ever so slightly out of kilter and I think it must have been, despite his huge achievements, a frustrating career in some ways.

I should say that these deficiencies have been minor, and they make very little dent in most people’s enjoyment of Paul Simon. But they have, it seems, made a dent in Paul Simon’s enjoyment of Paul Simon.

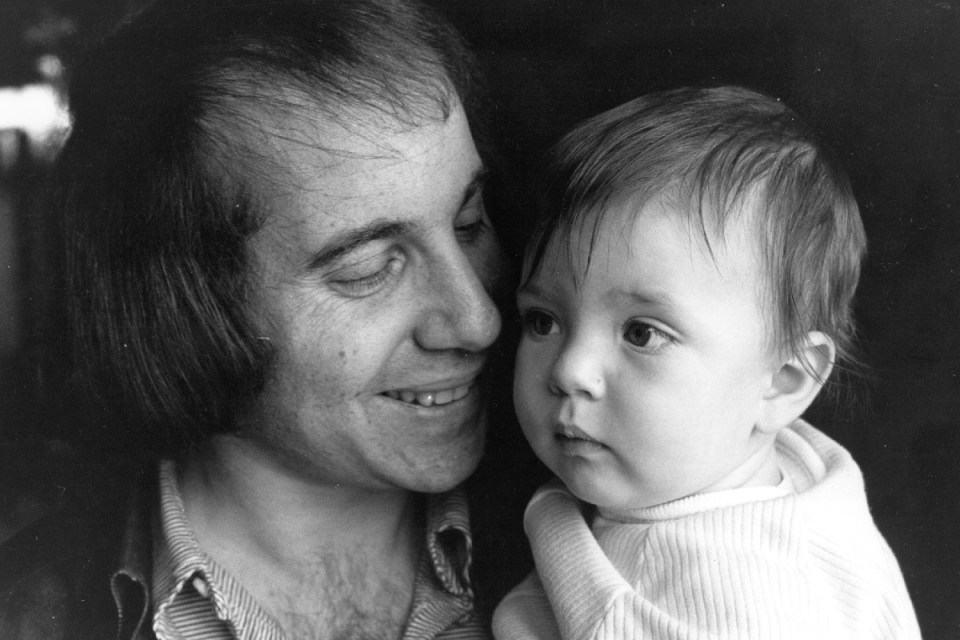

For the rest of us we have a body of work which is full of charm, occasional wisdom – and almost always, a beautiful gift for melody which actually surpasses Dylan, and is probably only dwarfed in post-war song by Paul McCartney. Simon has always had the knack of writing a song which you can grasp on first listen but which you want to listen to again. We are extremely lucky to have a lullaby like ‘St Judy’s Comet’, which can still get my son reliably to sleep as he enters his ninth year; that perfect (except for the last verse) gospel song ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’; ‘Mrs Robinson’ and many others.

But if we take Paul Simon at his own estimate as in some way second tier, it strikes me to be of enormous interest that Seven Psalms came to him in the way it did – as something gifted through dream.

We cannot say how this may have happened – and it is beyond the scope of this article to consider satisfactorily why we dream, and what dreams may mean. All we know is that dreaming is psychologically necessary. There have been experiments where people have been woken up just before REM – the period twice per night when we dream – and though they have slept, they have been denied dream. Such people have very quickly drifted into psychosis. From this we can realise that dreaming is psychologically necessary – a vital sorting of the day’s information.

Forever Jung

But there have long been thinkers, including Carl Jung, who have argued that dream is a form of essential communication, and that this isn’t best understood as a purely internal process. For such thinkers, our mind is open when we dream to the stream of external life, and it is this which constitutes the real necessity about dream.

Be that as it may, we can see in Simon that something utterly essential has happened in Seven Psalms: we can see that his career would simply not have made any sense without it – though we noted no particular gap before. This is the wonderful thing about living a long time. A Paul Simon who had for some reason died in his 70s, without having done this, would be a completely different and inferior Paul Simon. Something similar happened to the Australian poet Clive James: he was a completely different creature at 80 to 70 and even 75.

Seven Psalms then is an album which should give us all hope that if we continue to live we will continue to learn – and perhaps something may just land in our laps which we weren’t expecting. This might not be something as big as Seven Psalms – it doesn’t need to be.

In fact, for all of us, in whatever career or task we’re chiefly working at, life is usually giving us little indications which might be seen as microscopic versions of these larger realisations. The lesson from the life of Paul Simon is to stay alert for the big change in direction, the essential shift in the self. It may just come your way – and if it does, you’ll know how much you needed it.