August interest rate cut in doubt despite inflation falling to target

Inflation fell back to the two per cent target in May, prompting champagne corks to go flying in CCHQ.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said it was “great news” that inflation was back to target, describing it as another sign that the economy had “turned a corner”.

The figures showed that falling energy prices and easing food inflation helped pull the headline rate of inflation down to its lowest level since July 2021.

Although the fall compared to April’s figure of 2.3 per cent was not huge, it is still an important and symbolic moment.

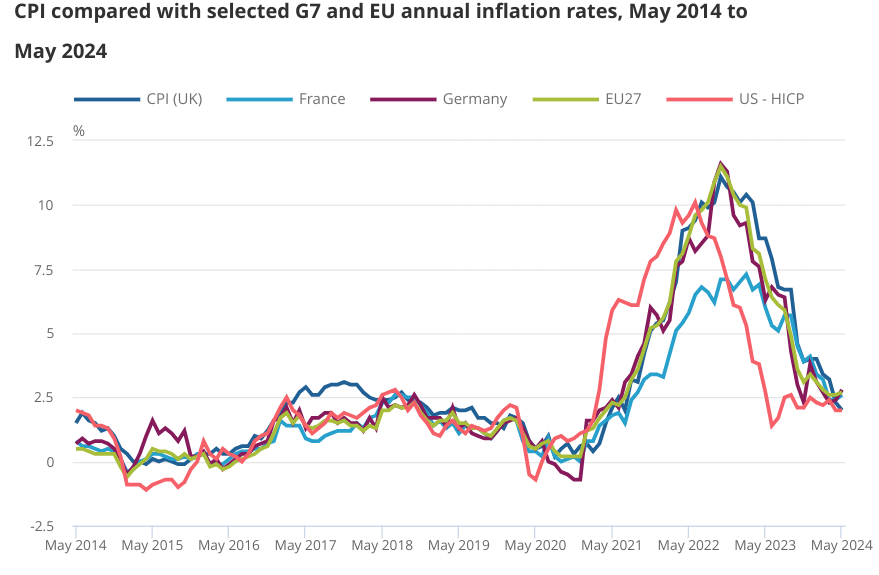

It means the headline rate of inflation is the second lowest in the G7. This is particularly striking given the UK was seen as an inflation outlier last summer, when inflation peaked at over 11 per cent.

But rate-setters at the Bank of England might be a bit slower to crack out the fizz.

The big question for the Bank is whether domestic inflationary pressures are firmly under control. After all, the headline rate of inflation is heavily influenced by trends in the global economy, which the Bank of England cannot control.

Its decisions on interest rates largely reflect developments in domestic inflation, and these indicators are less positive.

For a start, its worth pointing out that core inflation – generally seen as a more accurate gauge of underlying price pressures – is higher than both the eurozone and the US. It fell to 3.5 per cent in May.

The biggest concern though is that services inflation only fell to 5.7 per cent in May, down from 5.9 per cent in April.

Looking slightly longer term, services inflation has barely budged from February, when it stood at 6.1 per cent. The UK economy is dominated by the services sector, making it a good measure of domestic inflation.

Rob Wood, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said services inflation has proved “remarkably persistent” while James Smith, research director at the Resolution Foundation, said it will give the Bank “pause for thought”.

One of the main drivers of services inflation is labour costs, which is why rate-setters have been keeping a close eye on how pay growth is evolving.

There too, the trend is not moving as fast as the Bank would like. Annual pay growth in the private sector came in at 5.8 per cent in the most recent batch of figures, roughly double the level consistent with the Bank’s two per cent target.

April’s near 10 per cent increase in the Minimum Wage has likely contributed to stubborn pay growth.

All this is reflected in market expectations for interest rate cuts. Nobody expects an interest rate cut tomorrow, but markets actually pared back bets on an August cut after this morning’s figures.

Following the figures, Pantheon’s Wood said he was “very likely” to shift his call for the first rate cut from August to September.

Sanjay Raja, Deutsche Bank’s chief UK economist, agreed that the figures will “raise the bar for an August rate cut,” but said a big question for the Bank is how much stock they put on one, “arguably backward-looking”, piece of data.

Forward looking surveys have painted a slightly rosier picture, so all is not lost. But a summer rate cut seems to be slipping further and further away.