How has Brexit impacted migration?

Migration is likely to be an increasingly contentious issue over the next few years with over a third of voters saying it is the most important issue facing the country.

This is perhaps not surprising. Following the pandemic, net migration rose to unprecedented levels despite the vote to leave the European Union (EU).

Its probably fair to assume that, for most Brexit voters, ‘taking back control’ was not a vote to increase migration significantly. Nevertheless, that has been the effect. Both major parties are now committed to bringing migration down.

Fortunately, the UK in a Changing Europe (UKICE) think tank has put together a new report explaining what’s happened and why.

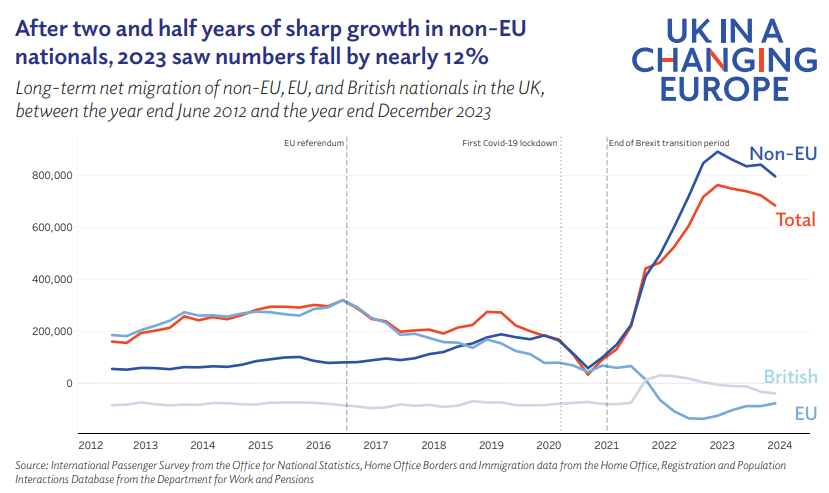

The most obvious shift has been the dramatic and rapid shift in migration from EU and non-EU countries.

Net non-EU migration has amounted to over 2m in the last three years, up from an average of just over 100,000 a year during the previous decade.

In contrast, EU migration has been on a downward trend since the Brexit vote, with net migration turning negative in late 2021. This means more EU citizens are leaving the UK than arriving.

What’s been driving the changes in immigration?

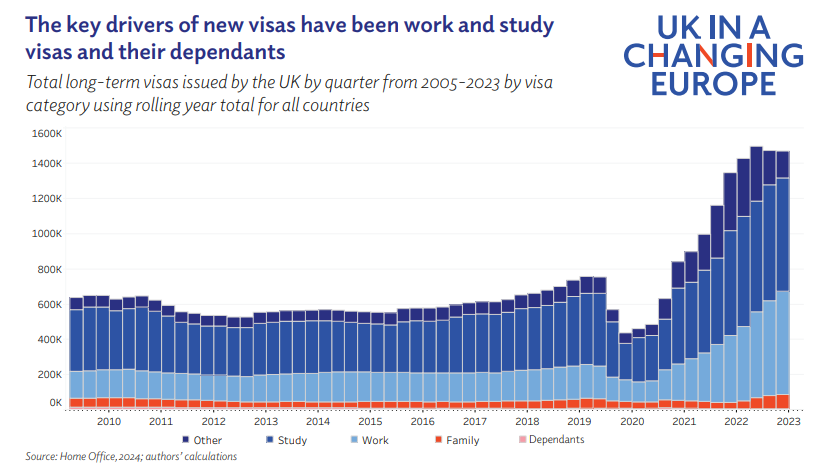

While all the main categories of migration have grown, the key drivers have been the increase in the number of work visas and study visas, as well as their dependants.

One of the reasons non-EU migration has increased is brute need. In the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, and with many EU workers leaving the UK, many sectors faced labour shortages.

“This was particularly acute in sectors where significant numbers of EU-origin migrants had left the workforce,” Jonathan Portes, senior research fellow at UKICE said.

Health and social care is a particularly clear example, with domestic workers choosing to leave the poor conditions in the care sector just as demand increased rapidly post-pandemic.

The government made it easier for all care workers to secure a visa given the severe shortages. Visas within the health and social care sectors now account for two-thirds of all work visas, according to UKICE.

Turning to study visas, the government reintroduced a ‘Post-Study Work Visa‘ in 2021, which allowed international students at UK universities to stay for up to two years after finishing a degree.

The visa had been abolished in 2012 but was brought back after lobbying from universities, amid concerns that the departure of EU students would leave them facing a big funding gap. A recent report from the Migration Advisory Committee found the graduate visa roue should remain because it helps the competitiveness of UK universities.

So, in both of the major cases, the increase in non-EU migration reflected a need to compensate for lower migration from the EU. These needs were only intensified by the pandemic.

Add on top of this the big refugee inflows from Hong Kong and Ukraine and you get some very high numbers.

The important thing, UKICE argues, is that these flows were the result of choices that needed to be made after Brexit.

“Brexit did indeed enable the UK government to ‘take back control’ of immigration policy. The current migration debate reflects the choices policymakers have made, balancing opportunities and challenges, and the effects – both anticipated and not– of those choices,” the report noted.