Silicon Valley Bank one year on: Is another banking crisis around the corner?

There were nervous flashbacks for banking regulators last week as, one year on from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, another regional US lender began to wobble.

While the troubles facing New York Community Bancorp were of a different making, it cast minds back to the banking crisis that tore through the US last year and rippled across the Atlantic to the UK.

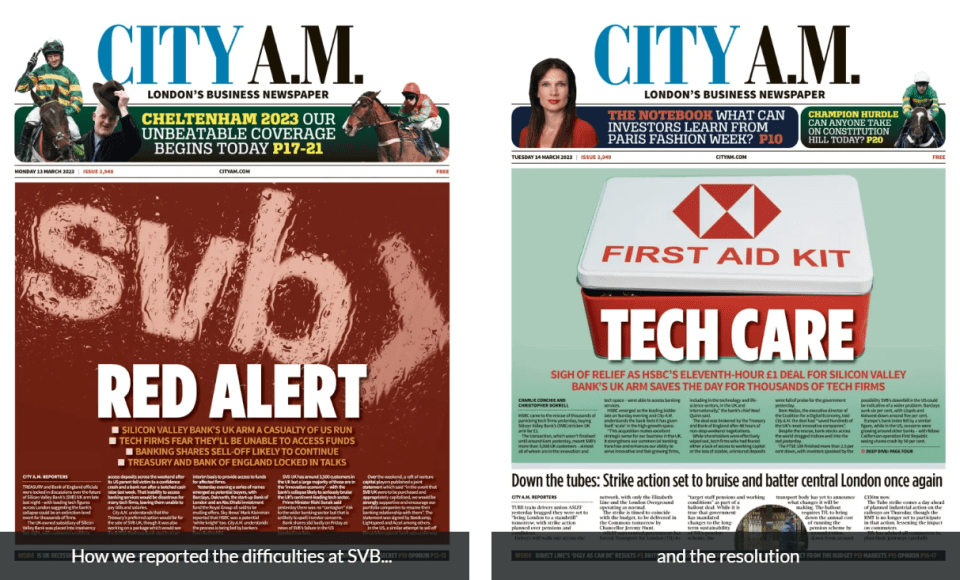

The implosion of SVB shook the British start-up industry and triggered a government-led rescue effort in which ministers and tech figures scrambled to find a lifeline for the firm over a single weekend. Hours before the market opened on Monday morning, HSBC swooped in as a saviour.

Looking back a year on from the crisis, those working at the firm now known as HSBC Innovation Banking are keen to put the crisis in the rear view mirror.

“I’m not gonna sit here and say that it wasn’t quite a difficult situation,” Simon Bumfrey, head of technology & life science at HSBC Innovation Banking, tells City A.M. “It was a tough nine or 10 months for our clients, our investors, our people.

“But the really positive thing to come out of it was that we managed to get through this transition in probably a three or four month period, which would have otherwise taken probably 18 months.”

Competition

The revival of the Silicon Valley Bank UK and its transition to HSBC Innovation Banking in June has been a commercially shrewd move for HSBC. In its full year numbers last year, HSBC reported a gain of $1.6bn on the deal after buying the firm for a solitary £1. The bank was also given a dominant and ready-made footprint in the start-up world.

However, that revival was not before scores of competitors pounced. SVB once dominated the start-up and venture capital market but has now been forced to compete. Bumfrey admits that competitors “saw it as a gap”, and peers say they are now well and truly on the pitch when trying to win business from HSBC Innovation Banking.

JP Morgan has dramatically stepped up its ambition in the market, hiring nearly 20 people last July as part of a beefed-up innovation economy division – some of which were former SVB employees.

Rosh Wijayarathna, head of innovation economy for UK & Ireland at JP Morgan and formerly of SVB, told City A.M. last year that the collapse of SVB “didn’t change the plan, only expedited it”.

“We wanted to be a major player around the world, and when a major player goes under overnight, that speeds the plan up,” he said.

Canadian-headquartered lender CIBC is another of the firms looking to make inroads. Chief Sean Duffy tells City A.M. “there’s lots of other people that are competing for the same thing now”, whereas SVB would logically have been the “go-to for growth companies” 12 months ago.

Another trend to have fuelled competition is the brutal wake-up called delivered to companies last March. Many had placed all their eggs in one basket and found themselves unable to make payroll and access cash when SVB began to wobble. Now they’re looking to soften that risk.

“If you’re a treasurer or a finance director with £20m, you should spread that between three institutions, and that’s what they’re doing now. And that’s a good thing,” Duffy says.

Bumfrey concedes too there was a “natural migration” of deposits away from SVB as bosses look to hedge against the potential threat of another SVB-style crisis.

Regulators have also looked to step in and beef up their defences against another bank run. The Bank of England is now actively monitoring social media to identify and nullify social media fears spreading that could lead to rushed withdrawals. Global financial regulators are due to publish a “deep dive” in October looking at how social media can speed up bank deposit outflows and whether changes to liquidity rules are needed.

‘It’s inevitable this will happen again’

But even with more vigilant watchdogs and a softening of concentration risk in the start-up sector, some bosses are warning the wider banking system is still vulnerable to contagion.

Emma Hagan, former chief risk officer for Europe and the Middle East at SVB and incoming UK CEO at Clearbank, says it is “inevitable this will happen again”.

“It’s inevitable given the inherent vulnerabilities within the banking sector and the rapid dissemination of information via social media platforms,” she adds. “Traditional banks, especially those who have been slow to adapt, may find themselves particularly at risk.”

While not fuelled by social media, fears of contagion have already reared their head in recent weeks over banks’ exposure to the US’ $5.8tn (£4.6tn) commercial real estate market, which has been hurt by higher interest rates, tumbling property valuations and a post-Covid shift to remote work and shopping.

New York Community Bancorp was rescued from disaster by a $1bn capital raise last week after its stock hit its lowest level since 1996. The bank hiked its loan loss provision to $552m in late January and took a $2.4bn goodwill impairment at the start of March, partly due to bad commercial real estate loans.

There are already fears that other smaller banks may be caught up in the storm. Analysts at Goldman Sachs have estimated that US banks carry around $2.7tn in commercial real estate loans, with some 80 per held by regional lenders. Morgan Stanley analysts have highlighted Bank OZK and Valley National Bancorp’s high exposure, with commercial real estate loans representing around 63 per cent of OZK’s earning assets.

“There’s news about some interesting dynamics playing out in the US,” Hagan adds. “Could some of that lead to the same kind of issue occurring? Potentially.”