A podcast on the Brianna Ghey trial is part of the enduring tradition of true crime

Crusaders against true crime have been duly granted the next subject of their outrage. The Daily Mail’s new podcast ‘The Trial: Brianna Ghey’ has offered itself up as the latest in moral panic triggers.

This is the third season of this Mail podcast; series one focused on the murderer Lucy Letby. It will report from the trial every day. One reason for the focus on Brianna Ghey rather than the ‘villain’ is that the boy and girl accused of the young girl’s murder are both too young to be named.

The marketing for the Mail’s new series proved particularly egregious. And it’s certainly horribly distasteful, featuring a huge picture of the titular victim, who was tragically killed in February this year, as it’s cover art. The advert – a full page of Tuesday’s paper – features a banner saying “From the team behind the global smash hit podcast The Trial of Lucy Letby’ and a floating box screaming ‘Follow every twist and turn from the courtroom’.

Using a murdered girl as a promotional tool feels wrong. But the Lucy Letby podcast proved a hit – winning accolades from woke-adjacent Alistair Campbell and others for its thoroughness. This podcast too will draw in listeners in droves.

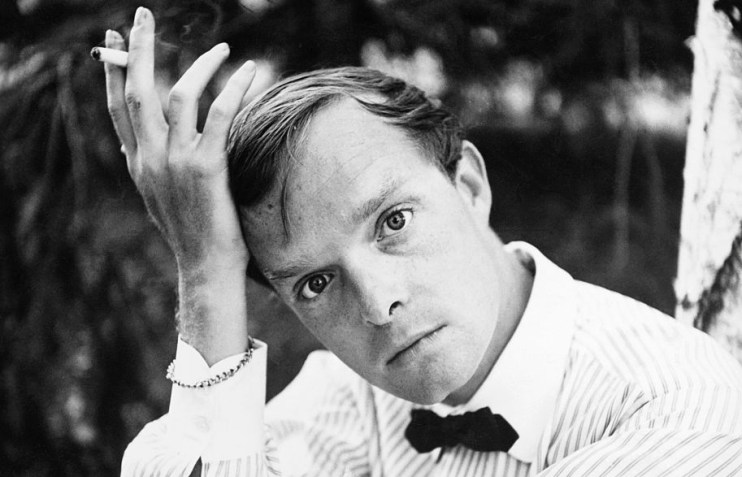

The truth is most people enjoy the phenomenon of crime entertainment in some form or other – whether it’s the podcast My Favourite Murder, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Stephen King’s latest novel which sees victims dismembered and cannibalised, or the Economist’s coverage of the murder of Jamal Khashoggi.

Whilst critics will bemoan the use of crime – and specifically the horrific murder of a child – as entertainment, there is an argument in the Mail’s defence. Isn’t a daily podcast surmising events in the courtroom – without proffering personal opinions or theories – really just an evolution of the old tradition of crime reporting that emerged in the 18th century?

A history of true crime: when punishment goes behind doors, we only want it more

Despite the widespread misbelief that Sarah Koenig’s Serial plucked the phenomenon out of thin air, true crime has existed for centuries, albeit not in such an Americanised digestible podcast format. Its ascendancy correlates with the demise of the Bloody Code – the name given to the period of English legal history during which a huge number of crimes (even stealing a rabbit or wreaking a fishpond) were punishable by death. Public hangings brought huge crowds.

At this time newspapers were the medium of choice. Expensive (as the government had slapped stamp duty tax on them to limit their ability to critique the powers that were) people gathered in the reading rooms of pubs or coffee houses to hear articles read aloud. And crime, for these papers, became an obsession. In the 18th century, Britain was only lightly policed. Victims often turned to newspapers to advertise stolen property, for example.

After the 1832 Reform Act, independent MPs began to chip away at repealing the Bloody Code. Prisons and professional police forces came into their own. A punishment system more akin to today’s began to take hold. Violence was pushed behind closed doors. Urbanisation and the fear of urbanisation came hand in hand.

This created the perfect context for a culture of dramatisation and exaggeration to flourish. Newspaper took advantage. Michel Foucault writes that a historical cultural shift in which “a whole aesthetic rewriting of crime” occurred in the 18th and 19th centuries, amounting to “the discovery of the beauty and greatness of crime” – but also the profitability of it.

In 1855 the hated Stamp Tax was finally removed, releasing the full forces of a cheap press. This was only compounded by decline in costs of printing and paper. Circulation increased. High-profile crimes like murders drew in customers – the more gruesome the better – with papers often publishing twice a day to deliver the latest court or police reports. Details of crime, offender and victim became more important.

“Crime is glorified, because it is one of the fine arts,” wrote Michel Foucault in his cult classic text Discipline and Punish. The public, maybe, need in some capacity to process crime, to witness transgression and to reflect on its significance to society.

To sideline or outlaw violence leaves a void. “[M]urder is the supreme event. […] Murder prowls the confines of the law, on one side or the other, above or below it; it frequents power, sometimes against and sometimes with it. The narrative of murder settles into this dangerous area; it provides the communication between interdict and subjection, anonymity and heroism; through it infamy attains immortality,” Foucault writes.

The 20th century French philosopher-sociologist would likely not be surprised that the fine art of crime is increasingly being pummelled into the ever-popular podcast format. University of Birmingham academic Lisa Downing writes “Foucault suggests that we might read reports and accounts about murderers not [only] to learn more about murders and those who commit them, but [primarily] to learn more about the society which produces them, the sorts of discourses that are made around them, and the normalising forms of power that happen to be in contestation and/ or ascendancy at the time of the crimes.”

So it seems that as much as true crime’s remit and packaging is rather repulsive, and our addiction to it less than savoury, it is by no means a new phenomenon, nor is it entirely voyeuristic.

So it seems that as much as true crime’s remit and packaging is rather repulsive, and our addiction to it less than savoury, it is by no means a new phenomenon, nor is it entirely voyeuristic.

Mike Dodd, a journalist and lawyer, argues that podcasts like the Mail’s Lucy Letby series are in fact just a new form of court reporting. In it, two journalists report from the trial each day – and talk to experts in different fields too. Dodd explains court reporting is important “for the public. If the public doesn’t know what’s going on in courts they have no idea whether justice is being administered or whether the system is working”.

It’s true that justice behind closed doors is a frightening prospect. And over the past years court reporting has become a vanishingly rare occupation. Dodd points out that in the past, court reporters could sell their output to multiple papers at the end of the day, but now once the information is online it’s free cop. If no news comes out of a court session, newspapers are unlikely to want to pay to cover it. In court journalists are able to call courts out when they mess up.That means without journos in courts, more and more justice goes on without as much accountability.

There is a credible moral imperative to report crime. Wrapping it up in a jingly little podcast with theme music and fun hosts is galling in the extreme – and the Mail’s Brianna Ghey podcast should undoubtedly have been created in better taste

Unintended side effects

There are side effects to the phenomenon of true crime. Women especially love the genre – and there is evidence to suggest they fear for their safety more than necessary (men in Britain for example are far more likely to be attacked yet it is women who are the subject of safety concerns). In both the US and UK interest in personal safety measures like doorbell CCTV has grown, but crime numbers are actually going down. Helicopter parents prevent children playing outdoors. The dominance of crime in media and entertainment is surely to blame for this odd, paranoid and unnatural tendency.

There is a credible moral imperative to report crime. Wrapping it up in a jingly little podcast with theme music and fun hosts is galling in the extreme – and the Mail’s Brianna Ghey podcast should undoubtedly have been created in better taste.

But ultimately it is a fault in the human psyche that craves the abject and the violent – from a distance usually. Is it the responsibility of media houses to dictate what we should and shouldn’t enjoy? To an extent, sure – there are a long list of things that should not be published – but these true crime productions are all fully within the remit of the law. We might find the enjoyment of crime and true crime repulsive but as Foucault explains, humans have an irrepressible urge to witness crime and punishment. Some would say it’s better than watching a live flogging, after all.