Five charts the Bank of England will study ahead of Thursday’s interest rate decision

The Bank of England is meeting tomorrow for its latest interest rate decision with markets almost certain that rates will be left on hold.

Underlying this certainty, however, are a number of moving parts.

Although inflation is slowly coming down, warning lights are flashing across much of the UK economy. Growth is slowing, unemployment is rising and forward looking surveys paint a bleak picture.

Here are five of the things that the rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) will focus on tommorow.

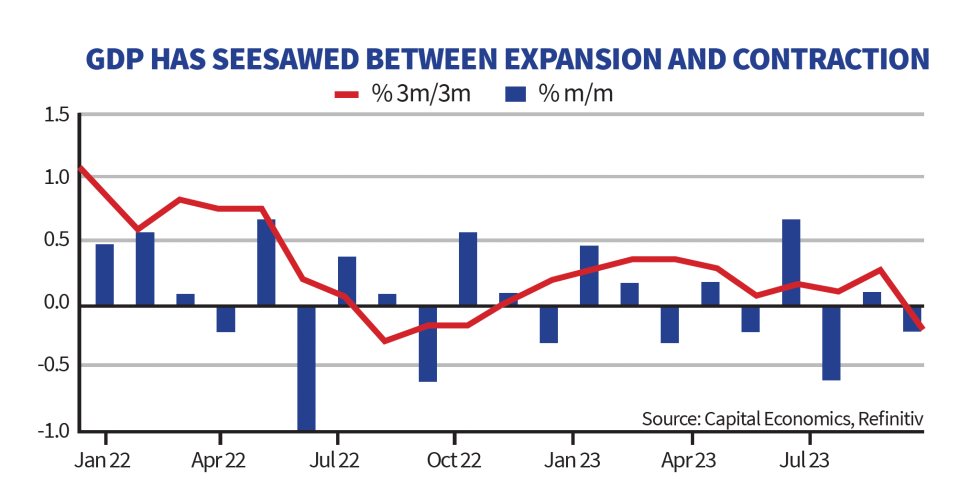

Growth

Although GDP has seesawed between expansion and contraction over the past few months, the long run trend paints a clear picture of slow growth.

GDP is likely to have contracted over the third quarter meaning the UK is at risk over falling into a recession over the second half of the year.

The danger for the Bank of England is that much of the impact of its rate hikes have yet to be felt thanks to the famous long and variable lags of monetary policy. Estimates vary, but it is likely that at least half has yet to filter through to the economy.

This is an important reason why economists expect rates to be left on hold. Any further hikes would likely tip the economy into an unnecessary recession.

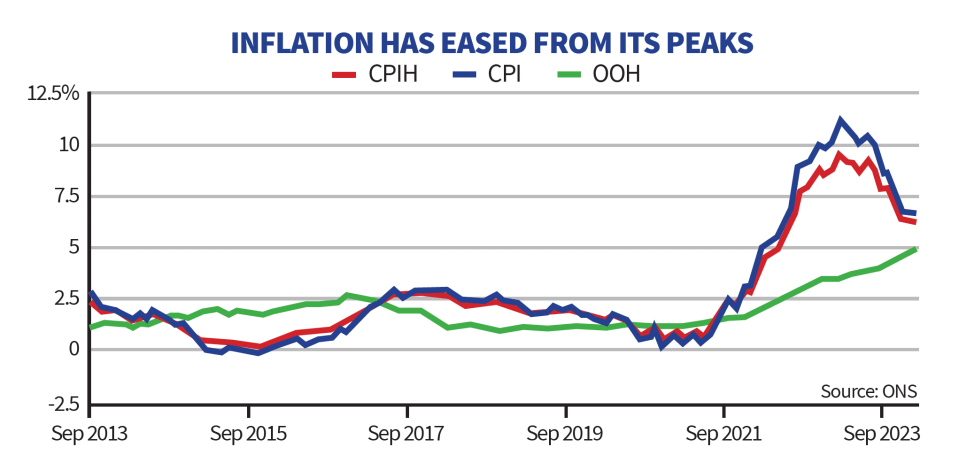

Inflation

Inflation is down on its peak in October 2022. This is largely thanks to falling energy prices but it also reflects the impact of the Bank’s monetary tightening.

While inflation remained stuck at 6.7 per cent last month, price rises are expected to ease further going forward. Many economists argue the impact of Ofgem’s price cap will see inflation fall to just over five per cent next month.

Policymakers will also be paying close attention to services inflation, which the MPC judges as a more accurate gauge of domestic inflation. After a sharp fall in August, services inflation picked up again last month – but it is unlikely to be enough to prompt another rate hike just yet.

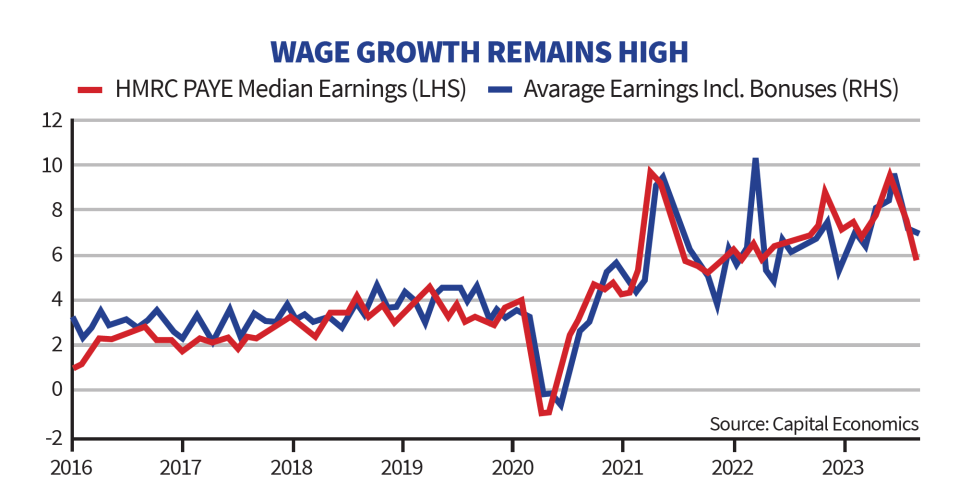

Wage growth

Wage growth is another gauge which MPC members are using to assess the extent to which inflation is domestically driven.

Including bonuses, annual wage growth dropped to 8.1 per cent in the three months to September. This was down from 8.5 per cent in the previous three month period, but still means wages are growing at near record pace.

The Bank has been persistently surprised by the strength of wage growth over recent months, which has raised the prospect of a wage-price spiral, which is when workers demand higher wages to keep up with inflation, forcing firms paying wages to hike costs further.

However, in its September meeting, the Bank of England noted that the Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures were difficult to reconcile with other estimates. Chief economist Huw Pill suggested the ONS figures are “increasingly an outlier” in estimates for wage growth, meaning more weight is likely to be put on survey data.

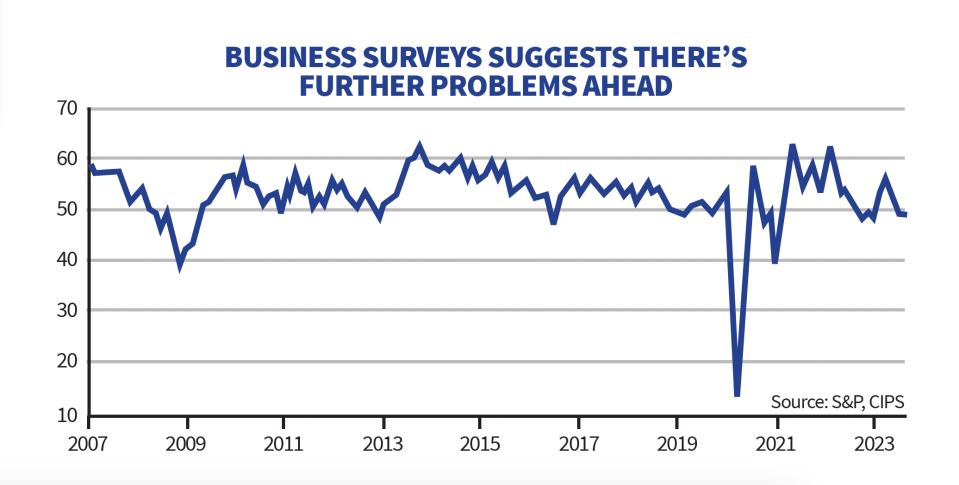

PMI survey

Business surveys are another helpful indicator for assessing the performance of the UK economy and give some forward guidance on what upcoming data will look like.

The most recent purchasing managers’ index from S&P and CIPS, put private sector activity at 48.6, below the 50 reading that indicates flat growth.

The UK’s all important services sector fell to a nine month low of 49.2 with survey respondents commenting on weak consumer confidence and higher borrowing costs.

Large revisions to September’s PMI mean October’s figures will be taken with a pinch of salt, but the downward trend over the last few months is hard to ignore.

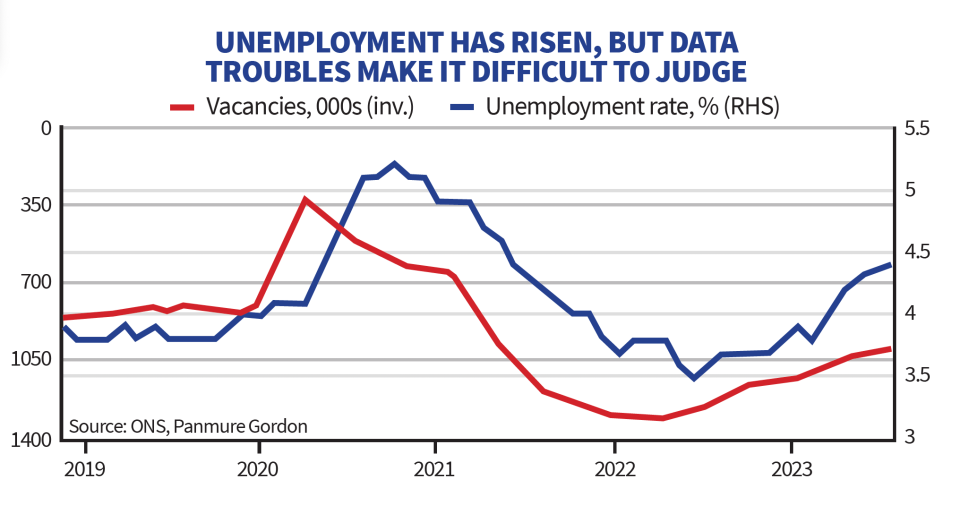

Unemployment

Speaking of concerns over data, the Bank of England will struggle to get an accurate picture of the labour market in this week’s meeting after the ONS published “experimental” data.

Thanks to falling responses to its Labour Force Survey, the ONS opted to use other sources of data which put the rate of unemployment between June and August was 4.2 per cent.

The new figures put unemployment slightly lower than previous data suggested but still above the Bank’s August forecasts. Yet it remains unclear just how much the labour market has been affected by the Bank’s rate hikes.

Without clear data, policymakers are moving in the dark to a certain extent. Economists at Pantheon Macroeconomics said there is a “clear risk that the experimental measures imply that the labour market is tighter than it really is”.