Should we be paying more attention to the money supply in fight against inflation?

The surge in inflation over the past few years caught most central banks and many economists by surprise.

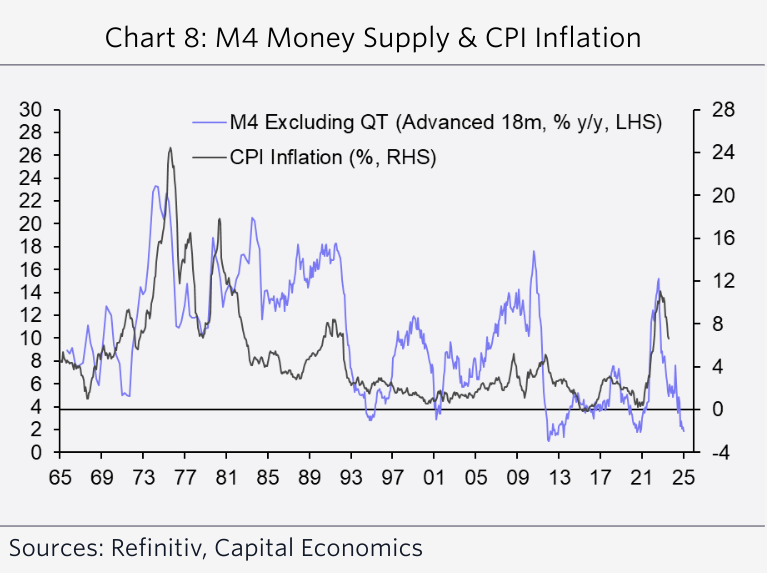

But those who kept a close eye on changes to the money supply warned months before prices started to rise that inflation was a risk.

Now, they are pointing to rapid falls in the money supply as evidence that the economy is slowing and inflation will fall. So are policymakers paying close enough attention to developments in the money supply?

On a basic level, the money supply is a simple concept. It measures the sum total of all the currency and liquid assets in a country’s economy.

A school of economists, known as monetarists, argue that changes to the money supply are by far the single most important factor driving inflation. As Milton Friedman, monetarism’s most famous advocate, said: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”.

Damian Pudner, director of the Institute of International Monetary Research, explained the logic. “Increases in the growth of broad money not matched by the rate of growth of the quantity of goods and services initially lead to strong asset prices and a boom, followed by a marked upturn in inflation,” he said.

This is what many monetarists argue the Bank missed in 2021.

Pudner highlighted that broad money growth was 15.4 per cent in the year to February 2021, with much of this driven by quantitative easing. He argued it was “no surprise” that headline inflation then surged to over 11 per cent in October 2022.

Pudner argued the failure of the Bank to give sufficient weight to changes in the money supply was a “glaring oversight”.

Bank officials reject the idea that they have not taken into account developments in the money supply.

Speaking to MPs on the Treasury Committee, governor Andrew Bailey stressed that the Bank does take into account monetary issues. “Of course, money is important; of course it [inflation] is a monetary phenomenon,” he said.

The Bank’s rate-setters point out there are a number of different methods for measuring the money supply – not all of which point in the same direction.

A range of factors influence how changes in the money supply feed through into consumer spending patterns. This means there are difficulties in drawing a direct correlation between changes in the money supply and inflation.

For example, broad money grew more than twice as rapidly in the years leading up to the global financial crisis in 2008 than in the decade or so after. In both periods, inflation was around two per cent.

Ashley Webb, UK economist at Capital Economics, argued “the relationship between money growth and real GDP and CPI inflation isn’t very strong”.

So where are we now?

Bank of England data shows that growth in the Bank’s preferred measure of money supply, known as M4ex, turned negative in August for the first time since data was collected. Using other measures, broad money has declined for the first time since the 1960s.

Webb suggested that around a third of the easing in broad money growth stemmed from quantitative tightening – the Bank’s bond selling programme – with the remainder made up by rises in interest rates.

As interest rates rise, funds have moved into higher-yielding assets, such as NS&I deposits, which are not included in the money supply.

“The decline in money growth shows that higher interest rates are working,” Webb said.

To a monetarist these are clear warning signals that economic activity is about to slow. Many warned the Bank of England should not hike interest rates again, a warning which was heeded – albeit monetary considerations were likely not a major consideration.

In the minutes for the latest MPC meeting, the word ‘money’ only appeared once. Still this was better than August, when it did not appear at all.