House prices will eventually start to fall, as long as owners accept their new reality

House prices are on the rise because fewer people are selling, and fewer people are selling because they think their property has preserved its value. Once they give up, prices will fall, writes Paul Ormerod

Economic news has had few moments of optimism lately: living standards are being squeezed and the overall level of economic activity, as measured by GDP, remains lower than it was in the second half of 2019.

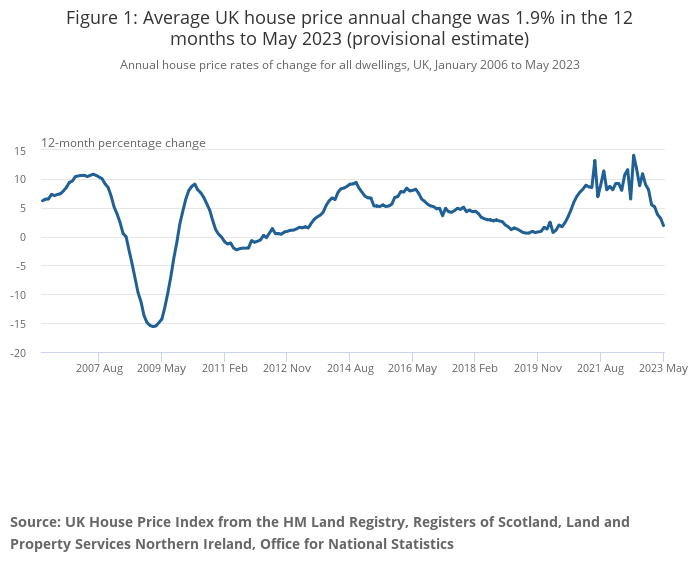

Yet house prices are holding up well. In the year to May 2023 average house prices are estimated to have risen by 1.9 per cent, and fresh data for June from the Land Registry, out today, is expected to reflect this.

The apparent puzzle – rising house prices in a period of economic stagnation – is readily resolved once we factor in inflation. Taking this into account, prices are down by around 8 per cent. This fall in real house prices, to use the jargon phrase, is exactly what has happened in previous economic slowdowns.

Between the first quarter of 1975 and the second quarter of 1977, actual house prices rose. But inflation was so high there was a fall in real terms of 19 per cent. In the next recession, from the end of 1979 into early 1982, the reduction in real house prices was 17 per cent.

The most dramatic fall was 1990-92, which was modest in terms of the reduction in GDP. But real house prices collapsed by 31 per cent. The final example is of course the financial crisis of the late 2000s, when there was a 20 per cent fall.

By the standards of these four previous episodes, the current reduction is of course modest. A plausible reason could be that we are not currently experiencing a recession. Output may be more or less flatlining, but it has not actually fallen.

But information at ground level suggests we’re in for further substantial falls. A Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors poll of estate agents and surveyors shows that the number of sales taking place is down sharply. In July a net 44 per cent said sales had fallen.

This is in fact a pretty dramatic figure; the same as it was in April 2020 when the country was under its most restrictive lockdown and uncertainty about Covid-19 was pervasive.

It is not just that there is a lack of interest from buyers. Fewer people are putting their homes up for sale.

Again, this is exactly what happened in previous periods of house price reductions. People continue to think that their own property has preserved its value, so even if they put the house on the market, they are reluctant to accept lower offers. And most buyers will not come in unless prices are reduced – especially as higher interest rates means the eventual cost is much higher.

As a result, fewer and fewer sales take place, and the market dries up. It takes time, but sellers do eventually realise what is going on. They reduce their house prices and the market gets going again to clear the backlog, but at considerably lower prices.

Your private view is that your house is worth a certain amount. The market, which gives the public information, says it is not. The longer the market contradicts it, the more likely you are to switch beliefs; once a few people in your area give in and start selling at lower prices, it creates a chain reaction.

We see a similar sort of process at work in stock markets. Cascades develop in which the players suddenly reassess the weights they place on public versus private opinion.

They are inherently difficult to predict. But both the state of the economy and the condition of the housing market suggest that there is still a long way to go for house prices.