Are central banks to blame for the inflation crisis?

As we enter what looks like the final leg of central banks’ interest rate rising journeys, it’s as good a time as ever to trace why they have been jolted into action after over a decade of ultra loose policy and whether their response to the inflation crisis has been effective.

Coming out of the worst of the pandemic in the summer of 2021, central banks should have seen that the conditions for inflation to return were lurking in the corners of the global economy.

International supply chains were stretched by a combination of ports suddenly closing at short notice due to virus outbreaks, workers being forced to stay at home and unusually high goods spending overwhelming suppliers.

Once lockdowns ended and citizens gradually returned to normal spending habits, demand for essential items like energy came roaring back, colliding with strained supply.

Judging these trends to be “transitory”, as the Federal Reserve, ECB and Bank of England did at the time, can be seen as justifiable. Staff would eventually return from the pandemic. There was little reason to think spending wouldn’t rebalance. Oil, gas and electricity production would rise in response to higher prices.

The bigger concern for central banks was that they didn’t know what shape their respective economies would be in after two years of being ravaged by the pandemic, delaying the start to their tightening cycles.

That’s not to say interest rate rises weren’t required. Signalling an inflation intolerance to financial markets, households and businesses helps retain credibility. Quantitative easing probably lasted too long and was too generous.

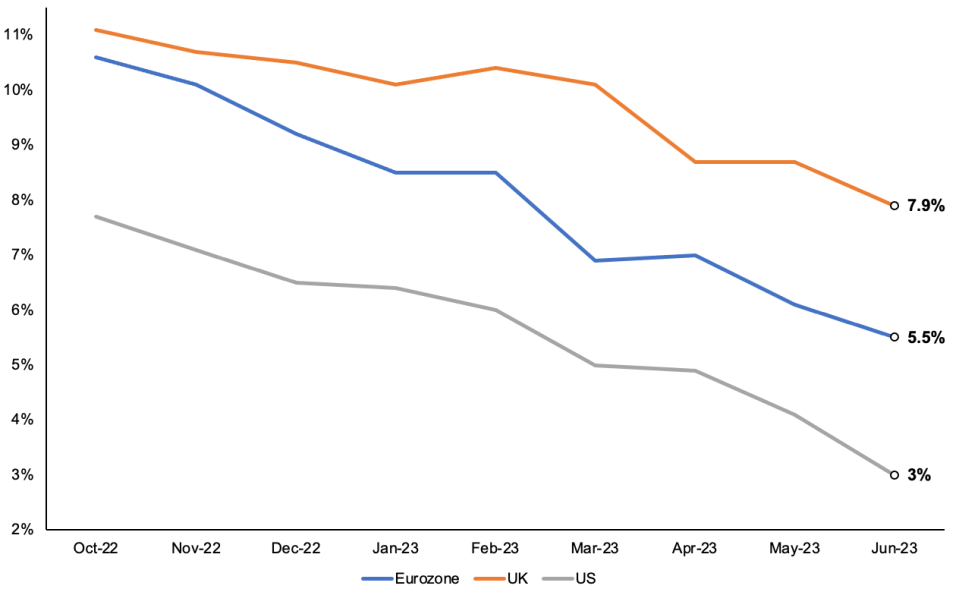

UK, Eurozone and US inflation rates

Everything changed in February 2022. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine could not have been foreseen. Its ramifications in energy and food markets were huge.

CPI in the UK jumped two percentage points in April to nine per cent. That was the biggest month on month annual increase since June 1979, according to modelled data from the Office for National Statistics.

In the US and eurozone, prices raced ahead. The dynamics required novel responses from central banks and they delivered. The Fed launched four 75 basis point rises. The ECB’s first increase was a smaller 50 basis points.

Those on Threadneedle Street were spurred into such action not by inflation but by the haphazard tax and spending decisions of Liz Truss during her premiership.

Kudos must be given to the Bank for its handling of that episode. It launched an emergency short-lived bond buying programme to hose down a fire in UK debt markets. Its 75 basis point increase went a way to tame higher inflation expectations.

Jerome Powell and co at the Fed have arguably been more aware of stimulative fiscal policy nudging up inflation. They went faster and steeper than their peers, partially to offset Americans pumping the up to $2,800 of parachute payments they received during the pandemic into the economy.

FOMC officials were also grappling with an inflation problem that was more demand driven, a factor that monetary policy is better at influencing.

Energy support packages were rolled out across Europe. France erected a more than €100bn support scheme, including capping prices. Germany doubled that gift. UK policymakers froze bills at £2,500.

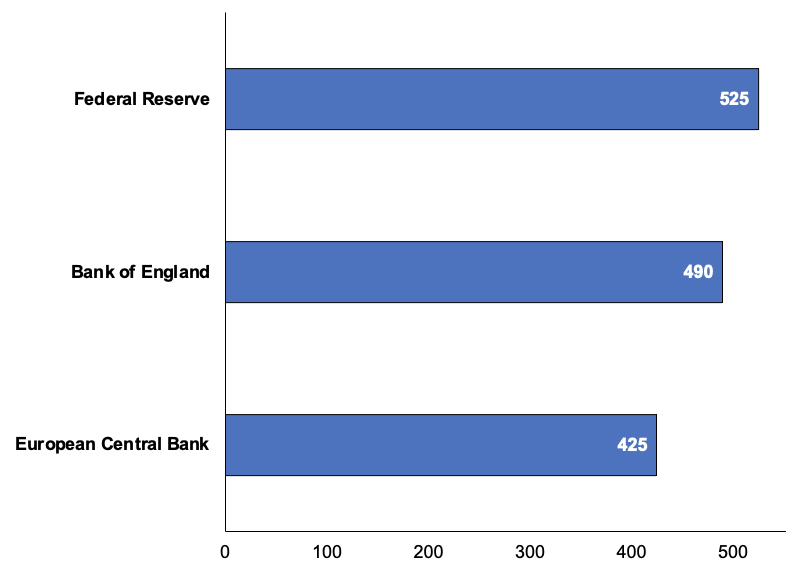

Cumulative tightening by ECB, Fed and BoE

All these measures were designed to blunt the initial shock from soaring gas prices. They were necessary to avert a living standards catastrophe.

By partly shielding incomes, governments supported spending and inflation. The tension between monetary and fiscal policy was there for all to see.

So how have central banks done? Inflation is three per cent in the US (lower than Japan), 5.3 per cent in the Eurozone and 7.9 per cent in the UK – all above target.

Doubtless the Fed, ECB and Bank of England have had some of their credibility knocked. Those on Threadneedle Street should be regretful of their terrible forecasting record over the last 18 months.

Central banks, though, as economist Mohamed El-Erian puts it, aren’t the “only game in town”. They are simply inflation stabilising vehicles navigating the economic conditions handed to them. To prevent future inflation flare ups, politicians and business leaders must be bolder.

Investment needs jolting, Infrastructure renewed, better jobs created. Mere tweaks to interest rates will not cut it.

WHAT I’M READING

There were some interesting stats in the Bank of England’s monthly money and credit report yesterday. Brits took on an additional £1.7bn of debt in June, £600m of which was from spending on their credit card. Perhaps that suggests families aren’t too bothered about higher interest rates. Or maybe elevated living costs are steering them towards debt. The overall sentiment of the snapshot though was that the full effects of the Bank’s 13 straight interest rate rises have yet to really crunch the economy. Home loans actually rose to 54,700 despite the initial stages of the mortgage rate surge taking place in June. P.S. This is my last column, but you can catch me over at The Thunderer in a couple weeks still jabbering about economics…