Shapps has fired the starting gun on UK nuclear hopes but there must be no more delays

Grant Shapps turned up fashionably late to the launch of industry vehicle Great British Nuclear, leaving everyone awaiting his arrival as if he was an ageing rock star stepping out on an arena tour.

Shapps wasn’t arriving with an obscure new concept album, though, instead the minister finally prepared to play the hits to an expectant crowd of energy enthusiasts.

This was encouraging, as irrespective of the secretary of state’s tardiness, there is nothing tantalising about the decades of delays in reviving the country’s nuclear ambitions.

The government has now clarified the role of GBN, putting meat on the bones of a high concept premise announced over a year ago, with the state-backed company set to oversee a competition for small modular reactors and help select new sites for nuclear projects, including full-scale GW plants.

Shapps even flashed the cash, putting a £20bn upper limit on setting out a pipeline for these scaled-down power plants, while also confirming over £100m in collective support for advanced nuclear reactors which could theoretically offer hydrogen energy.

Nuclear plans will fix a ‘colossal mistake’

The frontbench minister’s rhetoric was also surprisingly bold, condemning the neglect of Britain’s nuclear industry as a “colossal mistake.”

In the same week Oppenheimer is set to UK screens, Shapps seemed to invoke the spirit of the Manhattan Project when he slammed the developer-led approach of the past thirty years.

He argued this has led to nothing but delays, frustrations over funding and just one power plant being built in nearly thirty years – the over-budget and over-time Hinkley Point C in Somerset, that still awaits completion.

“We are heralding the beginning of a new nuclear age, a renaissance in Britain’s nuclear industry,” Shapps said, in front of a large painted canvas of the industrial revolution at London’s Science Museum, while also joking that he should be holding a hammer and sickle as he pledged to re-industrialise the country.

With the government’s energy ambitions plagued already by supply chain issues, planning obstacles, dovish investor sentiment and market competition, such a bold backing of nuclear power was surely welcome.

Nevertheless, questions remain over whether the government has done enough to realise its goal of reviving the country’s ageing fleet of reactors in such a tight timeframe.

Plan for funds, or plan to fail

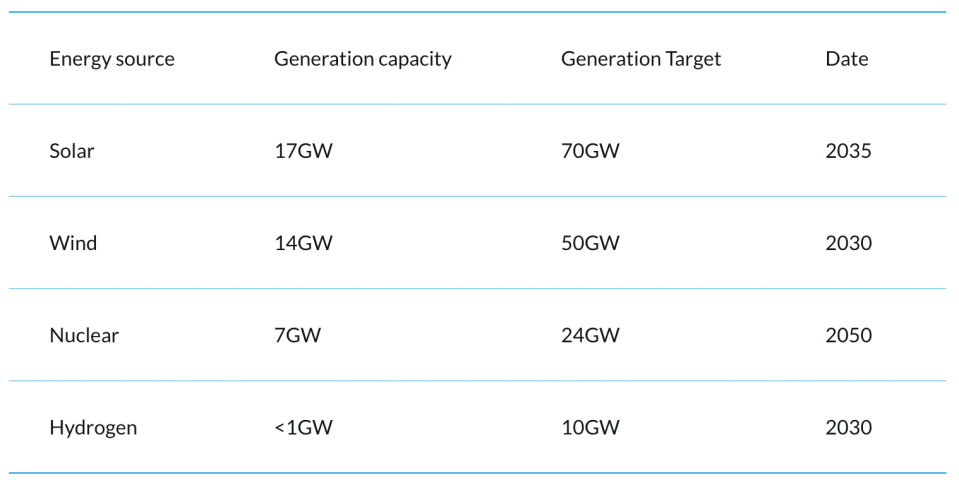

Downing Street’s ambitious energy security strategy includes ramping nuclear power from 7GW to 24GW over the next three decades, contributing to a quarter of the country’s future energy needs – with 85 per cent of current generation set to go offline within the next 12 years.

Much of that will come from the birth of a generation of ‘small modular reactors’ which are easier, and cheaper, to build.

In such circumstances, it is disappointing that no SMRs will be up and running until the early 2030s, with a final decision on any projects not expected this parliament.

The government’s backstop is 2029, meaning it could be six years before any project is greenlit.

The SMR competition is likely to include a number of runners and riders, with Rolls-Royce, Nuscale and Hitachi all in the running, yet the government could pick as few as two technologies to choose from, raising the risk of too many eggs in the basket of one company.

This is already a problem with the larger scale gigawatt power plants, as the UK’s hopes are currently in the hands EDF, the flagging French energy giant which required a full government takeover last year.

Hinkley Point C is on course to cost £33bn, well above initial expectations, while no announcements have been made on Sizewell C – a near identical power plant also being overseen by EDF – since last November.

These two plants could provide power to supply 12m homes, but the emphasis remains on could until they are built.

While Shapps is confident private sector investment can be found, publicly there have been no bites with UK investors still wary of supporting nuclear, despite new financing rules meaning taxpayers are on the hook for the initial construction stages.

This means there are real concerns over whether funding could be sustained for large-scale plants without immense government borrowing, which would have to be paid for by taxpayers – such as a third full-scale nuclear plant at Wylfa, North Wales.

Time is of the essence for new nuclear

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and repeated warnings over the lack of sufficient progress on electrification and emissions reductions from multiple climate bodies, time is truly of the essence.

Yet, there is no galvanising plan outlined for tackling local opposition to new projects, which could see plants scuppered under judicial reviews, or made electorally toxic for politicians.

Shapps has sought to be as diplomatic as possible, and when grilled over whether he would accept nuclear plants in his own backgarden, he said there would be no need as every day MPs were lobbying for their own constituencies to build new nuclear plants.

Yet YouGov polling shows around 40 per cent of the general public oppose power plants being built near them, in contrast to 17 per cent being against wind farms.

While some of this is fuelled by rare instances of disaster such as Chernobyl and Fukushima, it also reflects environmental concerns from charities about building in areas with diverse wildlife, and also over storage and maintenance with only a handful of sites suitable for plants.

These are all challenges Shapps and the government will have to face down if they want to revive the country’s nuclear ambitions.