Bank of England to raise interest rates for 13th time in a row this week to tame persistent inflation

The Bank of England is nailed on to raise interest rates for the thirteenth meeting in a row this Thursday, but markets think there’s an outside chance Governor Andrew Bailey and co will revert to an outsized rise to tame what is emerging as the worst inflation problem in the rich world.

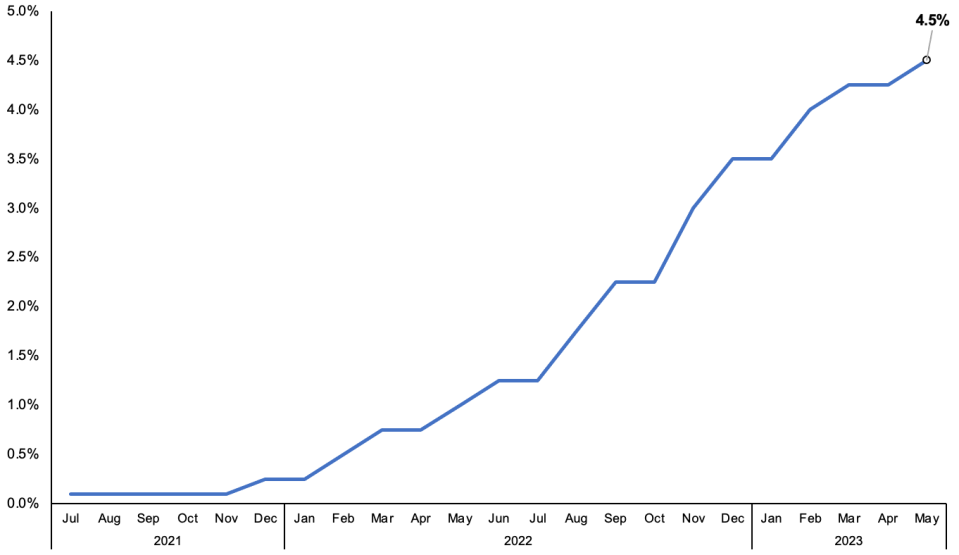

Markets reckon the nine-strong monetary policy committee (MPC) – the group of people who set official interest rates in Britain – will kick borrowing costs up 25 basis points to 4.75 per cent, taking them to their highest level since April 2008.

However, some think there’s an outside chance the MPC will lift rates 50 basis points, something they have not done since February, in order to signal to markets they are serious about bringing inflation back to the two per cent target.

“A 50 basis points increase seems less likely, but is not out of the question,” analysts at consultancy Oxford Economics said in a note to clients last week. Traders think there is an about 20 per cent chance of such a rise happening.

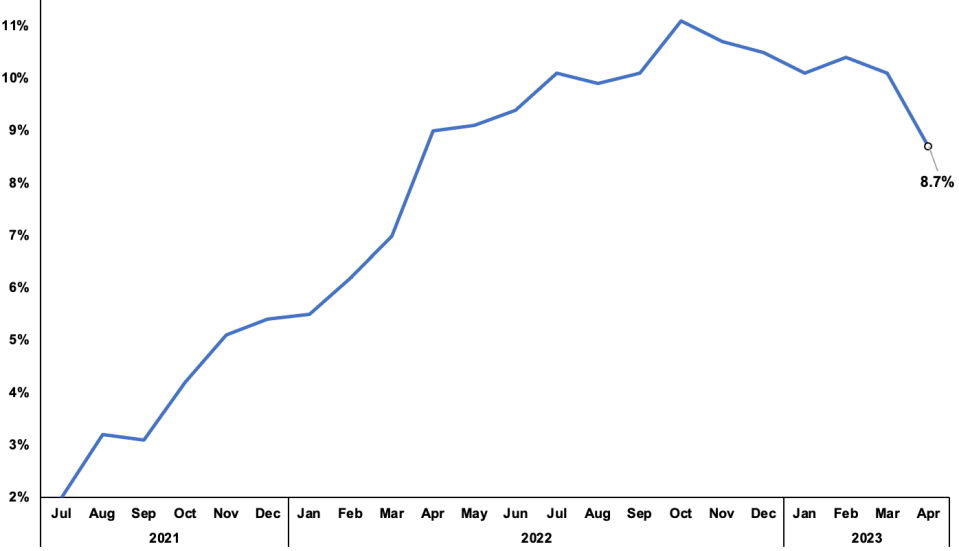

A string of data of late has indicated UK inflation is proving much harder to tackle compared to the US and Europe.

Prices have increased 8.7 per cent over the last year to April, a smaller than expected drop from 10.1 per cent in March. In America and Europe, inflation has dropped to four per cent and 6.1 per cent respectively.

Core inflation – which strips out energy and food price movements – leapt to 6.8 per cent from 6.2 per cent, while services inflation, which the Bank focuses on, also rose.

UK interest rates have risen sharply…

“The combination of these events has had a profound effect on Bank rate expectations, with the yield curve close to pricing in a terminal Bank rate of six per cent” last week, Philip Shaw, an economist at fund manager Investec, said.

Analysts think new inflation numbers on Wednesday will determine how hard the Bank goes on Thursday, with another sharp upside surprise raising the chances of a bigger rate increase. The consensus in the City is that inflation fell to 8.3 per cent in May.

There is also an expectation that the MPC will be split over what to do with borrowing costs. A majority of six are tipped to back a 25 basis point increases, while two could opt for keeping rates unchanged and one for a larger jump.

Economists have warned the risk of recession gripping the UK would rise significantly if the Bank were to meet market expectations and hoist borrowing costs to around six per cent.

A wave of around 1.5m homeowners rolling off of their existing lower-rate mortgage deals and onto contracts with much more punitive monthly repayments is tipped to drive the economic slowdown. Analysis from the Resolution Foundation has found that average annual mortgage repayments will climb £2,900 for this group next year.

Rates on 2-year and 5-year mortgages have pushed up to nearly six per cent in response to financial markets raising their peak Bank rate forecasts. Banks price their products on swap rates, which reflect market expectations of where officials interest rates are headed.

“Household spending will take a material hit at some stage, though it is unclear exactly when,” once the big mortgage reset kicks in, Shaw said.

… to tame scorching inflation

The structure of Britain’s mortgage market has shifted markedly since 2008 when a majority of homeowners took on loans with rates that were shaped around official interest rates.

Now, most Brits are on what are known as fixed mortgages, meaning they lock in the rate for a number of years.

While this has shielded Brits from the bulk of the Bank’s twelve successive interest rate increases, it has slowed the pace at which the central bank’s tightening cycle has fed through to the economy.

As a result, some experts think the Bank is at risk of engineering an unnecessary recession by not waiting to see the impact of its previous rate rises and continuing to pile pressure on families and businesses.

“We are acutely conscious that the risk of a policy error – of tightening too much” is mounthing, analysts at Japanese investment bank Nomura said.

If the Bank pushes the economy too far into a slump, it “could mean more drastic cuts in interest rates when the time comes,” they added.