Shell’s oil and gas embrace may woo investors, but it is short term thinking

Shell has slashed its green ambitions, reneging on pledges to cut back oil production while also ramping up payouts to shareholders.

At its capital investor day last week, the fossil fuel giant appeared to abandon its modest target of a 1-2 per cent cut in oil production year-on-year until the end of the decade, instead sustaining output and ensuring investors cash in on black gold’s chunky returns.

The FTSE 100 firm argues it has already reached its 1-2 per cent target – largely through hefty divestments – and remains publicly committed to its climate agenda.

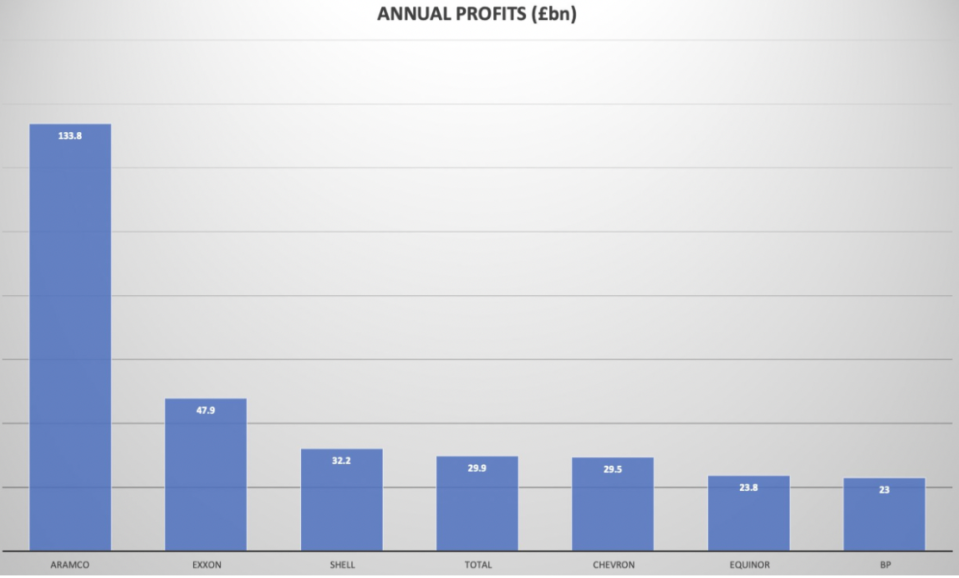

However, Shell’s embrace of oil and gas can easily be seen as a rebuke of net zero – and follows rival BP rowing back emissions targets this decade and US juggernaut Exxon Mobil recently describing the 2050 carbon emissions goal as ‘remote’.

It is now set to invest $40bn in fossil fuel production between 2023 and 2035, compared with between $10bn and $15bn in “low-carbon” products such as renewables over the same time period.

This reflects a clamour in the industry to harness high commodity prices, with investment in oil and gas exploration currently on course to reach $528bn this year, its highest level since 2015 – growing 11 per cent year-on-year.

Shell’s strategy was hammered by its usual critics, with investor activist group Follow This hoping it would be a “wake-up call” to climate-friendly shareholders, while Greenpeace argued the mask had now slipped and the energy giant was “showing their true colours”.

Climate-conscious asset manager LGIM has even called on Shell to explain how it plans to reach net zero emissions by 2050 while hiking investments in fossil fuels.

However, there is no need for alarmism or public declarations, with Shell’s decisions little more than a distraction from the wider picture.

The same day Shell unveiled its latest plans to shareholders, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicted that the peak in world in oil demand could be just five years away – putting a ticking clock under the plans of all fossil fuel majors.

Catch up, Shell! World is still going green

The Paris-based climate agency expects demand for oil will slow almost to a halt this decade, with a marriage of government energy strategies and consumer behaviour driving the change.

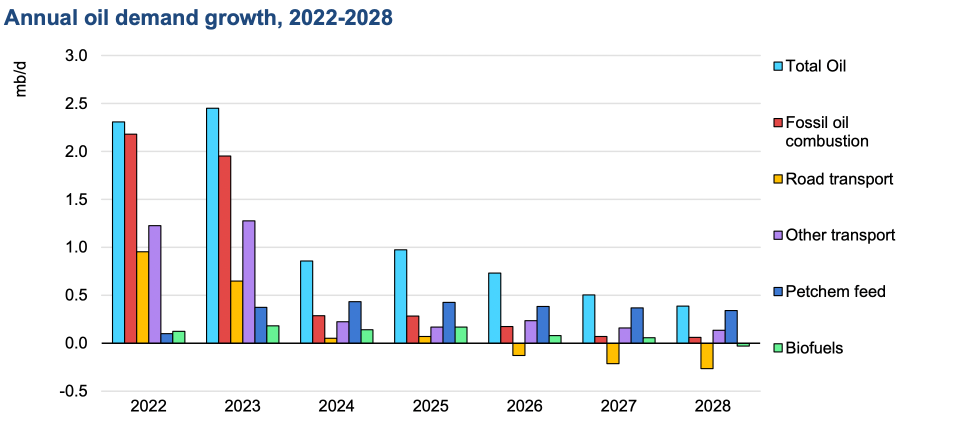

Its latest medium-term market report forecasts that global oil demand will rise just six per cent between 2022 and 2028 to reach 105.7m barrels per day – but that overall annual demand growth will shrivel from 2.4m barrels per day this year to just 0.4m in 2028, putting a peak in demand in sight.

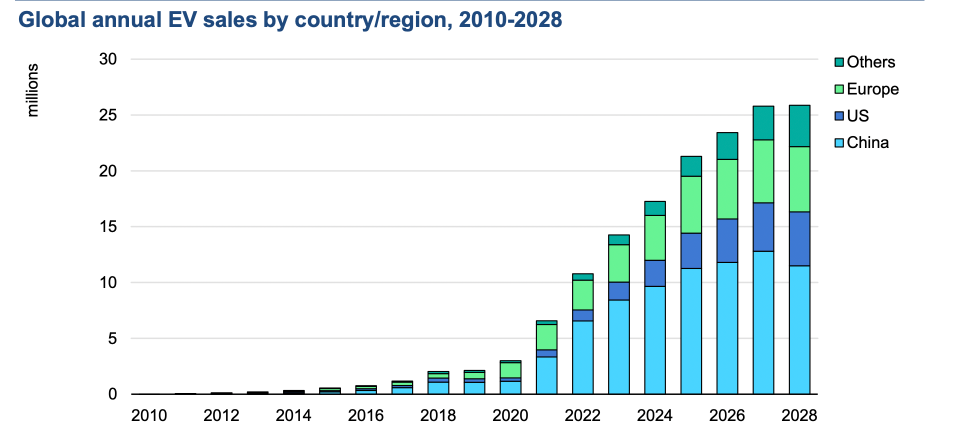

In particular, growth in oil demand for transport will crumble after 2026 as the expansion of electric vehicles, biofuels and improving fuel economy reduce consumption – reflecting how policy, business innovation and customer choices can make the world a greener place.

High oil and gas prices – which have fuelled the global energy crisis – are driving consumers towards greener alternatives for transport, power, and heating, while security of supply concerns following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year mean governments are focusing on energy policies powered by wind, solar, hydrogen and mass electrification of domestic energy networks.

This is being reflected in the data, with the IEA also predicting earlier this month that renewable energy capacity will jump a third this year – the largest annual increase ever recorded.

It expects the world’s total renewable capacity will rise to 4,500 gigawatts, equal to the total power output of China and the US combined.

The fundamental driver of this expansion is China – which will account for 55 per cent of global additions of renewable power capacity in both 2023 and 2024 – while the US Inflation Reduction Act has also begun luring investment across the Atlantic.

This does not mean the world is yet on course to reach net zero.

Thousands of renewable projects now exist in the global development pipeline but challenges such as upgrading grid connections, securing investment amid inflationary headwinds, easing planning laws, extracting minerals, and establishing supply chains have to be overcome to keep up with consumption demand over the coming decades.

The reality of reaching net zero will be a painful one, with difficult arguments to be had over how much we should expect our lifestyles to be changed, and how much we’re prepared to pay to reach these goals.

Oil and gas production and trading will be a factor – albeit a declining one – over the short and medium term.

This could even mean that while net zero is desirable, the time frame has to be extended beyond 2050.

Yet the shift to renewables is clearly underway, and this will help mitigate the damaging costs of not reaching net zero, and the wider environmental harms we all fear.

The current focus may be on oil majors embracing their chief source of income – fossil fuels – but a downturn in demand is coming, and this means Shell will be compelled to catch up if it wants to remain one of the world’s biggest energy giants.