Yes, inflation will fall – but back to Bank of England target? Well, that’s anyone’s guess

Inflation is definitely on its way down, but no thanks to the Bank of England – well, yet.

Most of the drop will be driven by energy price rises falling out of the ONS’s numbers.

Tomorrow’s figures are poised to start that descent, with the rate of inflation probably falling to around eight per cent in April from 10.1 per cent in March.

Once the rest hit, then the wonks on Threadneedle Street can claim to really be leading the fight to get inflation back to the official two per cent target.

It’s not where inflation’s headed this year that’ll be keeping Governor Andrew Bailey up at night. Instead, it’s where inflation settles over the very long term. As Bailey and other MPC members have warned, the risk of inflation staying higher for longer is “skewed to the upside”.

There are some unavoidable shifts in the global economic tectonic plates looming that threaten to throw the developed world into a higher inflation environment.

The UK and the world’s advanced economies are in the early stages of a long journey to much, much older populations.

In this country, the old-age dependency ratio – how many people of working age are there to those above the state pension age – is on track to reach two-to-one by 2070. It’s currently three-to-one.

The UK is by no means alone in suffering a steep increase in its elderly population.

South Korea is predicted to end up having nearly the same amount of old people to young people over the same period. Across advanced nations, the dependency ratio is poised to jump to just under 60 per cent from a little under a third.

This will have significant impacts on economies’ capacity to make things, all things equal. Companies will run into greater friction when sourcing staff amid a tighter workforce, putting upward pressure on wages and, eventually, prices.

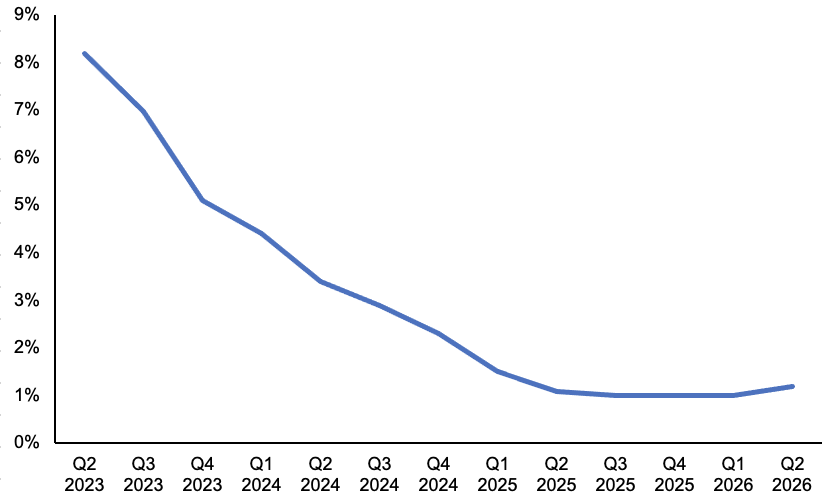

Bank of England inflation forecasts have it back to target by 2025

Aggregate supply would struggle to keep pace with demand, leaving consumers chasing fewer goods and services, amplifying inflation.

Demand would probably be crimped by governments hiking taxes to raise revenue to pay for greater healthcare spending to treat the elderly, leaning against prices.

Productivity improvements should offset some of those demographic changes, though the UK’s record in that area has been sub-par since the 2008 financial crisis.

Workers fashioning a greater amount of goods and services per hour pushes down the amount of money firms require to generate products. They can pass on that cost reduction to consumers or pocket higher profits. Competition would hopefully steer them toward the former.

Part of the reason the UK has been blindsided by the current inflation shock is stalling productivity growth.

Data from the ONS last week showed output per hour growth sunk to 0.6 per cent over the three months to March, the weakest improvement since 2013.

Britain’s transition to Net Zero is often identified as a means to reverse that flatlining trend.

Energy manufacturing and industrial sectors typically have a decent output expansion record. In the short term though, shifting companies toward more carbon neutral production methods will be costly.

Materials such as cobalt – used in battery cars – are tough to extract and refine into inputs that businesses can use to generate goods. Using such a mix of resources would create strong incentives to raise prices.

Advanced economies’ populations are set to get much, much older

Those same higher renewable energy prices, accelerated by government edicts that force consumption and production in a specific direction (like the UK requiring all new cars are electric or hybrid by 2030), should crowd in investment that hunts out profit, streamlining production and, eventually, bringing down costs.

The bill for all this economic-greening is going to balloon the UK’s debt pile. In their fiscal risks report, the OBR thinks after a brief slump, debt as a share of GDP will motor and peak at more than 250 per cent of GDP by 2070. Most of that is caused by higher healthcare spending and the Net Zero move.

A sustained upward march in borrowing isn’t good news for the pound and inflation. Investors would demand a discount to swallow all those extra bonds, either pushing debt rates higher or sterling lower, a similar dynamic to that which played out after Liz Truss’s mini-budget.

Shifts in the underlying macroeconomic structure are extremely abstract. Their effects don’t spring up suddenly, but emerge gradually over decades.

Nonetheless, it’s worth remembering there are some big changes to the global economy that are on the way over the coming decades.

They threaten to push inflation to a higher plane than we’ve been used to in recent history.

WHAT I’M READING

Last week’s labour market figures from the Office for National Statistics were roundly interpreted by economists as showing signs that tightness is unwinding. “It’s still more of a trickle than a tsunami, but the latest releases suggest that the tide may be turning for the labour market,” Paul Dales of Capital Economics put it. “Recent increases in labour supply have been heavily dependent on falling student numbers, while the level of people reporting they are long-term sick has continued to climb,” Oxford Economics said. Bank of England officials will need more signs of wage growth cooling to convince them that their fight against inflation is over.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

The US Federal Reserve may have ended its interest rate rise campaign to tame inflation at its last meeting. That’s the conclusion many traders would have drawn from a voting member of the FOMC Neel Kashkari’s interview with the Wall Street Journal. “I’m open to the idea that we can move a little bit more slowly from here,” he said. Inflation has been falling steadily in the US and the Fed has already raised rates aggressively to a range of five and 5.25 per cent.