Britain’s renters are the real victims of this inflation and interest rate crunch

People doubtless would’ve gasped at headlines last week about UK interest rates being on course for five per cent.

Such a path looked implausible in March when Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse and Credit Suisse’s shotgun marriage to UBS sparked fears of a financial market meltdown.

Now, certainly in the UK, when it comes to market expectations of where borrowing costs are headed, we’re back to levels not seen since the weeks after Liz Truss’s mini budget roiled the UK debt market.

After numbers from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) last week revealed inflation hung in the double digits last month at 10.1 per cent – above the Bank of England and City’s projections – traders hiked their peak rate forecasts sharply.

Make no mistake, that’s a huge jump. Yes, they expected another 25 basis point increase on 11 May before last Wednesday’s inflation numbers, but that was it.

Now Bank Governor Andrew Bailey and the rest of the monetary policy committee are poised to really strain the UK economy to get rid of the inflation beast.

Monetary policy has a few pipelines that channel its effects, with the housing market being among the most influential.

Higher mortgage rates and a greater risk of unemployment have sent UK house prices down for seven straight months, according to Nationwide’s data.

Banks have effectively forced people out of the market by passing on Bailey and co’s rate increases, meaning sellers have to slim asking prices to find buyers. With rates now on course for five per cent, the outlook for house prices has got a whole lot worse.

Mortgage rates will probably reverse some of their decline since the Truss-induced volatility.

That rise also risks engineering a lot of friction between landlords and tenants, a relationship that’s been strained ad infinitum.

Rates on buy-to-let mortgages – which landlords use to purchase a home to rent – have jumped from 3.22 per cent to 5.56 per cent over the last year, according to data provider Moneyfacts.

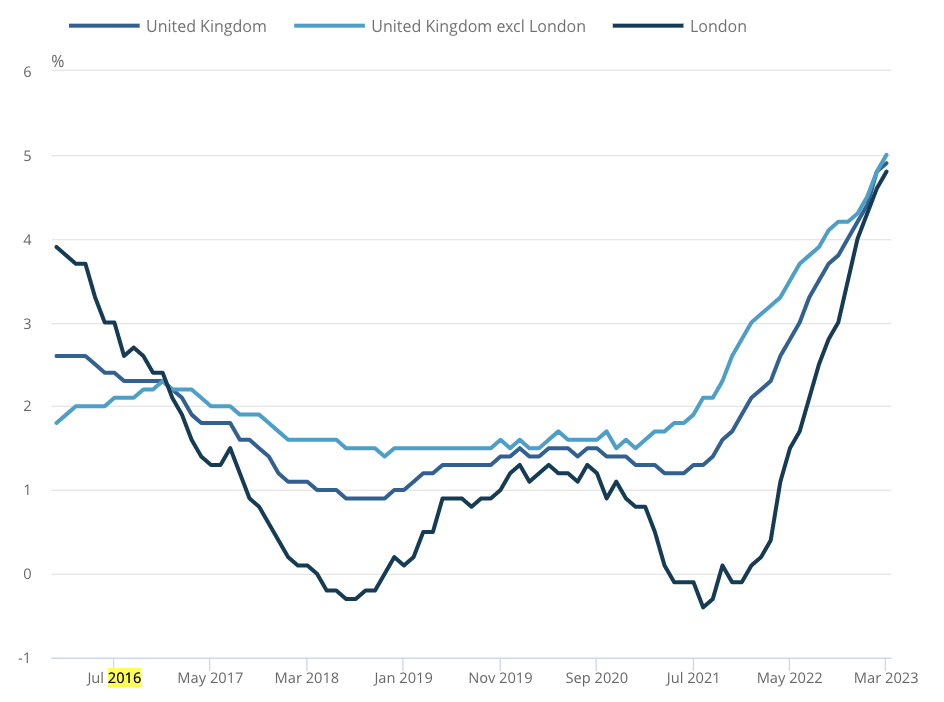

That surge has prompted landlords to hoist rents steeply over the last year. The ONS said last year rents leapt 4.9 per cent annually in March, the biggest rise since the data was first tracked in 2016.

Rents have been on an upward march

In London, they rose five per cent. Of course, that average hides some of the larger increases at the top of the range.

Renters are at the sharp end of the cost of living crisis. They typically have less income than homeowners, meaning a greater share of their finances are eaten up by housing bills.

Resolution Foundation research last week found they’ve been more likely to fall behind on rent payments than homeowners have on mortgage bills since inflation took off.

And there are signs that young, talented workers are fleeing London due to massive living costs or just shunning the capital altogether after they graduate.

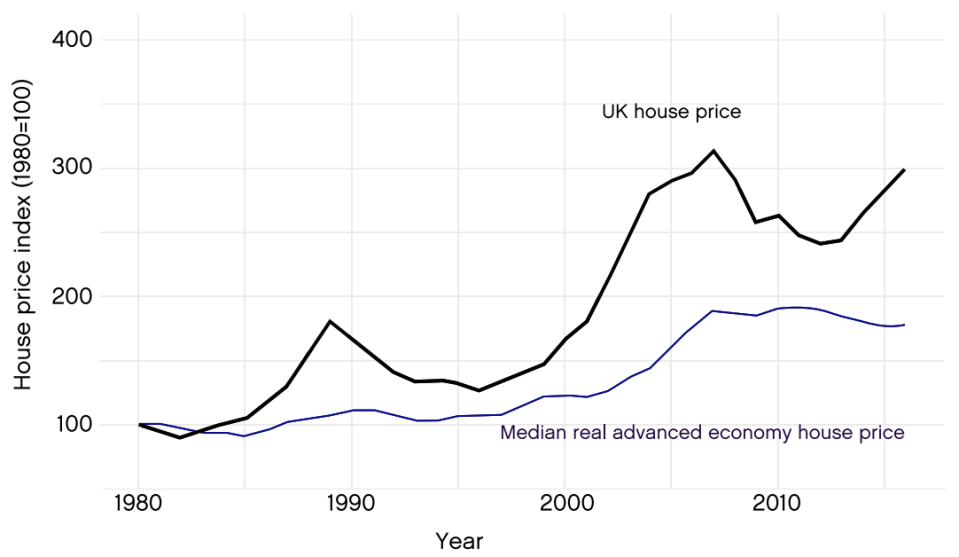

House prices have been turbocharged by ultra low interest rates since the financial crisis and quantitative easing pumping cheap cash in the economy.

UK house price growth has raced ahead of its peers

That has meant landlords have to borrow more to buy a home, pushing up rents.

More important than those two factors is bad supply. As research from the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) points out, countries in Europe have also had rock bottom rates for more than a decade, but house prices have not risen as much as in the UK.

“Despite having similar population growth over the period as a whole, both France and the Netherlands roughly doubled their housing stock, whereas the UK’s has grown by just 46 per cent. Accordingly, real house price increases in the UK have been more than double those of France and the Netherlands, even as interest rates have been broadly comparable,” a report penned by Alex Morton and Elizabeth Dunkley for the CPS found.

To rebalance the housing market so that people don’t have to shoulder unaffordable rents and offer young people a genuine chance of getting on the property ladder, we have to build more liveable and sustainable homes.

Providing immediate help to the poorest who can’t afford massive rent and mortgage bill increases is necessary to tackle hardship.

But fundamentally we need to pursue a policy mix that increases housing supply to prevent such sudden and sharp increases from happening in the first place.

WHAT I’M READING

We are – Morgan Stanley absolutely promise – very, very close to the end of the world’s central banks raising interest rates to tackle inflation. The coming round of meetings, which include everyone from the Federal Reserve, Bank of England and Bank of Japan to Sweden’s Riksbank (the world’s oldest monetary authority), are poised to mark the final rate increases in this current tightening cycle, Morgan Stanley’s analysts reckon.

YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED

Germany’s top economic indicator, the Ifo index, climbed for the seventh month in a row, to 93.6 this month from 93.2 in March. Analysts now reckon Europe’s largest economy has avoided a recession – for now.