City analysts betting on Bank of England interest rate cuts by early 2024 – as long as inflation falls quickly

The Bank of England could cut interest rates as soon as early next year if inflation continues to tumble in 2023, top City analysts have predicted.

The rate of price increases is forecast to more than halve which would bring inflation to below five per cent by the end of 2023, according to forecasts from the Bank and budget watchdog Office for Budget Responsibility.

Any such drop would water down the need for more interest rate hikes.

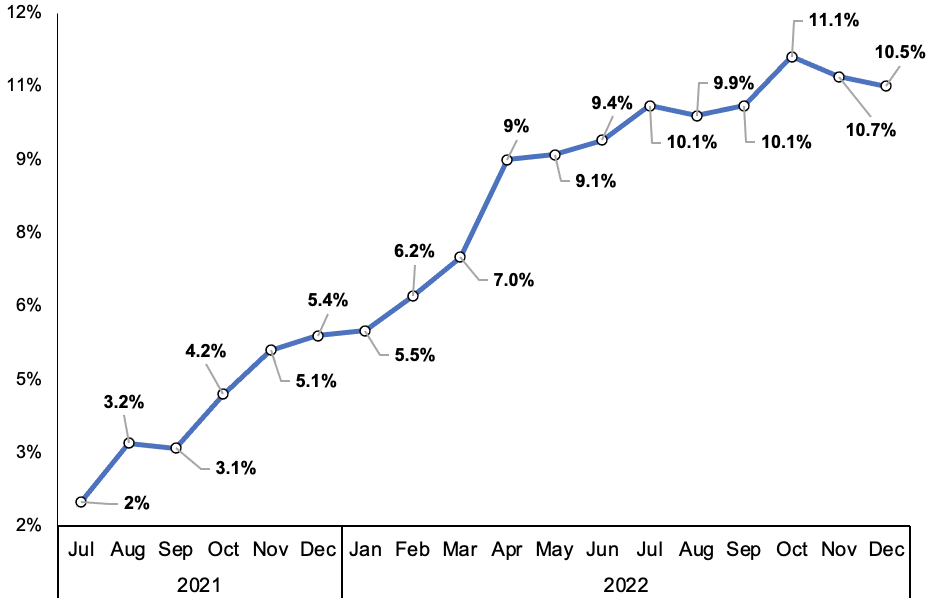

Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) showed that inflation in December fell for the second month in a row to 10.5 per cent in December from 10.7 per cent.

The drop was the first consecutive monthly decline for the first time since the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The slowdown was mainly driven by international energy prices collapsing after they surged to record highs following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a trend that is expected to continue throughout this year.

Gas prices are now lower than they were before the Russian president Vladimir Putin launched the assault on his neighbour.

Despite the fall, inflation is still running at more than five times the Bank’s two per cent target.

Core inflation – a more accurate measure of underlying price pressures – held steady at 6.3 per cent, raising concern over an inflationary feedback loop setting in.

However, analysts said core inflation is on track to slide quickly in 2023, opening the door for governor Andrew Bailey and the rest of the monetary policy committee (MPC) to drop borrowing costs.

“With imported goods prices set to fall back, labour market slack likely to build, energy inflation having peaked and profit margins under pressure, we think core CPI inflation will be within touching distance of two per cent by the end of this year,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said.

“If so, the MPC’s fears about ingrained high inflation should fade as 2023 progresses, bringing rate cuts into play in early 2024,” he added.

In theory, raising interest rates sucks demand out an economy by making it more attractive for consumers to save and more expensive for businesses to borrow.

James Smith, developed markets economist at Dutch bank ING, agreed with Tombs, forecasting the MPC will begin reducing borrowing costs “in the first quarter of next year,” but added cuts “could feasibly be a bit later than that” due to the risk of the UK suffering sticky inflation stemming from both a squeezed jobs market and exposure to high energy prices.

Inflation may have passed its peak

The Bank will announce its next rate decision on 2 February and investors are split over whether to back a 25 basis point or 50 basis point hike.

The latter would send borrowing costs to four per cent, a post-financial crisis high and mark the tenth successive increase.

Other analysts warned that the Bank will keep raising rates to prevent soaring wages – up a record more than seven per cent in the private sector – from sparking an inflationary spiral.

“With underlying inflation, activity and wage growth all ending last year a bit stronger than expected, we doubt the Bank of England will call time on rate hikes for a few months yet,” Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, said.

“Developments on the wages front continue to suggest that the MPC’s job is not done yet,” said Paul Hollingsworth, chief European economist at BNP Paribas.

Bailey and co have been forced to heap pressure on households and businesses by hiking rates to rein in spending to tame a 40-year high inflation surge.

Britain is this year widely expected to tip into a slow burning but shallow recession, caused by the cost of living crisis and higher rates chilling consumption, which will also put downward pressure on inflation.

MPC members are worried about piling unnecessary pressure on consumers and making any recession worse than it needs to be.

Markets think rates will peak at around 4.5 per cent.