The pandemic threw scientists into the limelight but not the scientific process

It is hard to believe that last week marked two years since the first person in the world received a licensed Covid-19 vaccine. Many hailed the pace at which the vaccine was developed. But behind this scene of unprecedented success lay an intricate network of researchers, scientists, and healthcare professionals, collaborating globally to deliver a breakthrough that saved millions of lives.

Two years on, we are still feeling the effects of Covid-19, but we’ve also been tackling outbreaks of resurgent viruses and bacterial diseases such as Mpox and Strep A. The scale of the Covid-19 pandemic taught us some hard lessons, but unless we act on those now, we will remain poorly prepared for coming health emergencies.

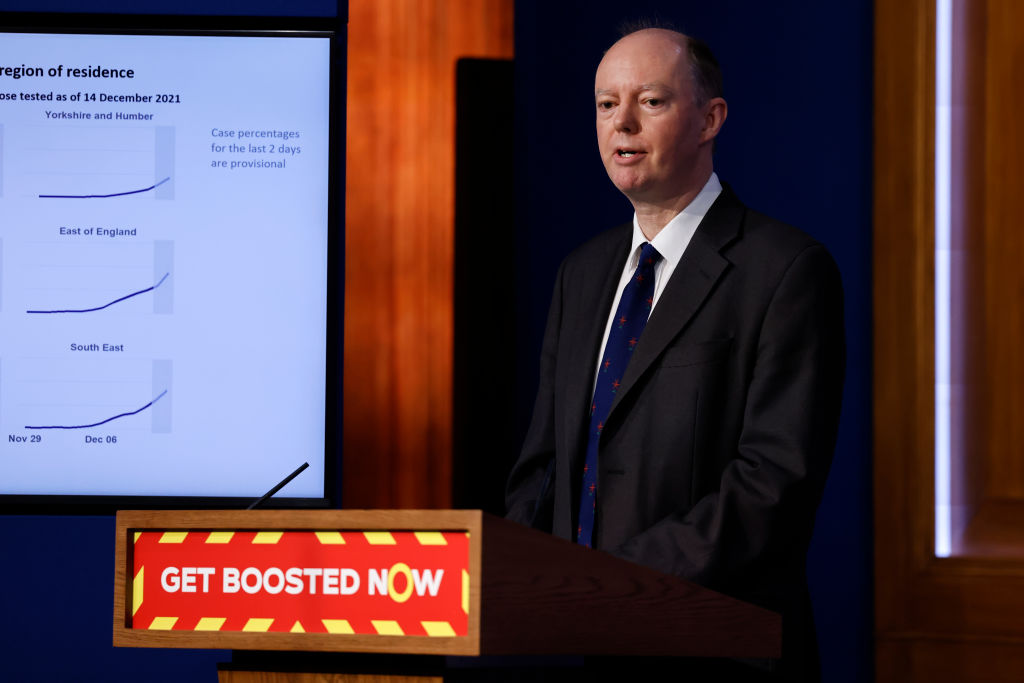

With the likes of Chris Whitty, Chief Medical Officer, and Patrick Vallance, Chief Scientific Advisor, turning into overnight celebrities with their daily Covid-19 briefings, the pandemic changed how scientists were perceived by the public. They were emblematic of a new era in which science and scientists are front and centre in the public eye. A recent report by the Economist Impact, a policy research team within The Economist Group, supported by The Lancet’s publisher Elsevier, surveyed over 3,000 scientific researchers globally. It found that although scientists recognised a welcome increase in public attention on science thanks to the pandemic, this awareness was not always matched by enhanced public understanding.

During the pandemic, it seemed that scientists were blamed for changes in policy and the general feeling of confusion about how to manage the rapid spread of a new coronavirus. To meet the demands of the pandemic, scientists had to forgo important elements of the research process, such as peer review, a crucial method of quality assurance that invites scrutiny of research by other experienced researchers (peers). This process, unsurprisingly, takes time, but without it we remove an important check and balance that helps ensure that findings can be relied upon by the public, media, and policymakers.

Public understanding of the iterative nature of science was also poor. New scientific findings are always provisional. “Facts” can change as new evidence is gathered and accumulated. Those outside the scientific community can sometimes find this uncertainty hard to accept, and for good reason. The public wanted black and white answers during the pandemic. But science is often grey. And when scientific advice did change, this was often met with criticism, or even alarm. The long-term effect of this might well be an increase in the mistrust of experts. Scientists have to do better and turn the tide through improved public understanding.

This much more public-facing role for scientists is now here to stay, which brings extreme challenges for researchers. Now it’s about using social media to reach the public, policymakers, and the media. But this means tackling misinformation – according to the Economist Impact’s report, a quarter of academics (23 per cent) now see publicly countering misinformation as one of their primary roles in society, compared with just 16 per cent who said this was the case pre-pandemic. Social media exposes scientists to an avalanche of abuse, with 32 per cent of those surveyed saying they had personally experienced, or knew a close colleague who had experienced abuse after posting their research online. But what does this ultimately mean? Researchers are nervous about using social media – just 18 per cent said they were confident communicating their research on social media.

The public, media and policymakers need to be better informed about how the scientific and research process works. There is an opportunity for us to do this now, which wasn’t possible during the height of the pandemic. Researchers need to be supported to improve their communication skills when engaging with the public and policymakers. We must pour investment into building public trust in science, campaign to counter misinformation, enhance research literacy among the media, commission more research on science communication, make vigorous efforts to explain new research findings to a public audience, and prepare scientists for more public-facing roles.

There presently exists extraordinary and dangerous complacency among many scientific bodies about the lessons of Covid-19. The attitude seems to be, “well, we developed effective vaccines in record time, didn’t we, so what is there to complain about?”. The future has to look brighter for scientists; otherwise, it can’t look brighter for us.