UK borrowing surges to £13.5bn on energy price cap support

UK borrowing surged over the last year due to the government partially covering the cost of household energy bills, official figures out today reveal.

The UK’s debt pile swelled £13.5bn last month, up more than £4bn compared to October 2021, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Although high, the figure was far below the £21bn predicted by City analysts.

Last month marked the start of the government’s £2,500 energy bill cap, first introduced by former prime minister Liz Truss for two years, but now slimmed down to one and raised to £3,000 in April by now chancellor Jeremy Hunt.

The trimmed version was part of a package designed to rebalance the country’s finances after Truss’s £45bn of unfunded tax cuts.

The autumn statement last week saw the chancellor raise taxes and cut public spending £55bn, most of which landing after the next general election, to shore up the country’s finances.

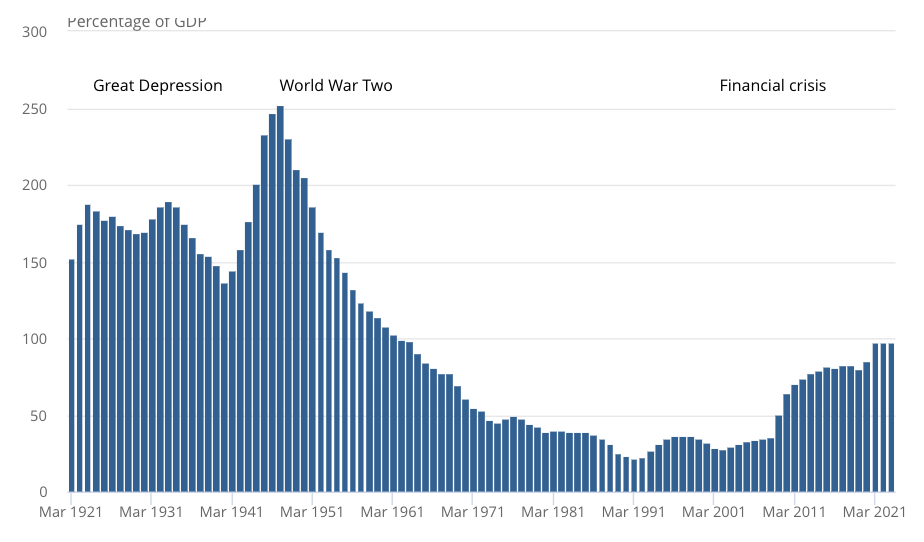

Hunt wants to get debt as a share of the economy falling in five years and cap borrowing to fund day-to-day spending at three per cent of GDP.

After the measures, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) judged Hunt will hit his targets. However, analysts today warned there are risks that could derail the public finances.

Consumers and business are being squeezed by soaring prices, up 11.1 per cent over the last year, prompting them to cut spending, softening the UK economy and the government’s tax revenues

“There are growing signs that the recent weakness in economic activity is holding back tax receipts. Total receipts in October of £70.2bn were £0.7bn (one per cent) lower than last October’s level,” Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, said.

The OBR reckons the UK will grow more than two per cent each year after 2024, mainly driven by productivity improvements. Since the financial crisis, Britain has suffered from terrible productivity growth.

The OBR’s “assumption that the trend rate of growth in output per hour is 1.3 per cent – double the rate seen in the 2010s – looks too optimistic, given that business investment is set to comprise a much smaller share of GDP over the next couple of years than in the previous decade,” Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said.

Weaker economic growth would reduce the government’s income, meaning Hunt would either have to raise taxes and cut spending further, or borrow to bridge the gap between spending and revenue.

“There is no easy path to balancing the nation’s books, but we have taken the necessary decisions to get debt falling while actively taking steps to protect jobs, public services and the most vulnerable,” the chancellor said today.

The debt to GDP ratio is above 97 per cent.

UK’s debt pile has swelled since pandemic