UK unemployment falls to 50 year-low amid jobs market exodus

A sharp rise in the number of Brits dropping out of the jobs market altogether has artificially pushed the UK unemployment rate down to its lowest level since the mid 1970s, official figures published today reveal.

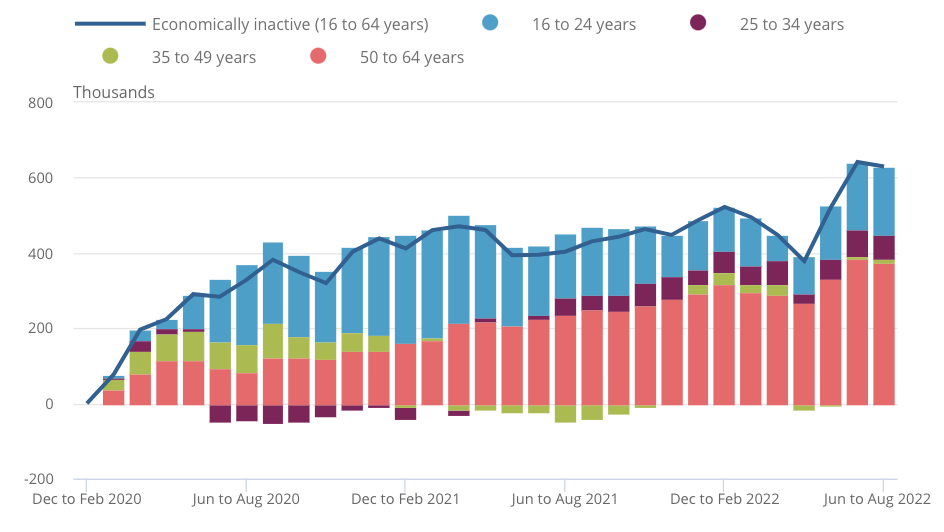

The volume of people in the UK not looking for work climbed around 330,000 over the last three months, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

That rise in what economists called people who are economically inactive forced the UK unemployment rate down to 3.5 per cent from 3.6 per cent.

The ONS does not include people who are not looking for a job in their jobless calculations, meaning the scale of Brits not in work is actually higher than the headline figure indicates.

Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng welcomed the stats, noting they “remind us that the fundamentals of the UK economy remain resilient”.

There has been a big rise in the pool of UK economically inactive people since the Covid-19 crisis, with nearly 1m more people not looking for work since February 2020.

Persistent illness caused by long-Covid has been identified as a potential driver pushing economic inactivity higher, however there are no official figures backing this up.

A swelling backlog of NHS work has led to people being unable to receive routine care, pushing them out of the jobs market, economists have noted.

UK economic inactivity has climbed sharply since the start of the pandemic

A shallower worker pool has tightened the UK labour market, meaning employers are competing with each other to lure talent. That has partially put upward pressure on wages.

“Growth in average total pay (including bonuses) was six per cent and growth in regular pay (excluding bonuses) was 5.4 per cent among employees,” the ONS said.

However, roaring inflation is eroding any pay rises workers pocket.

Accounting for price increases, total pay and regular pay slid 2.4 per cent and 2.9 per cent respectively, among the biggest drops since records began around 20 years ago.

Workers have voted for strike action to secure inflation-matching pay rises to protect their living standards.

However, strong wage growth is intensifying inflationary pressures in the UK economy by swelling businesses’ operating costs.

A lack of cooling in pay rises will prompt the Bank of England to keep hiking interest rates to tame inflation, City economists said.

“Today’s release provided only tentative signs that the labour market is turning,” Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, said.

“As such, we think the Bank of England will raise interest rates by at least 100 basis points in both November and December and eventually to a peak of five per cent,” she added.