Transport for London’s haphazard funding model must now be made fit for the future

SINCE the pandemic wiped out much of Transport for London’s fares income, London’s transport network has faced an existential crisis. The Elizabeth Line’s opening was a rare upbeat moment in a miserable couple of years of uncertainty for the city.

Lurching from one short-term bailout to the next – with highly charged negotiations taking place right up to the wire – has taken its toll on TfL. An inability to plan long-term is no way to run a major global city’s public transport system.

It is a critical few days for TfL and City Hall as the current funding deal ends on Friday. The mood music isn’t encouraging, and previous negotiations warn us to expect another stopgap lump of funding to tide over TfL for a few weeks.

This funding is crucial to keep the buses and tubes running. Because TfL must run a balanced budget, government money is needed in the short-term to fill the gap between outgoings and income.

City Hall and the Government fundamentally disagree over how long emergency funding is needed. Ministers demand TfL lives within its means, without subsidy. The Mayor argues without ongoing support for public transport, the city’s recovery and competitiveness is at risk.

Being the one with the money, the government holds the aces. Throughout this crisis, conditions imposed by them have seen fares increase, the scope of concessionary travel reduced and investment slashed. Might service cuts and a weakening of terms and conditions for TfL employees be next on the list?

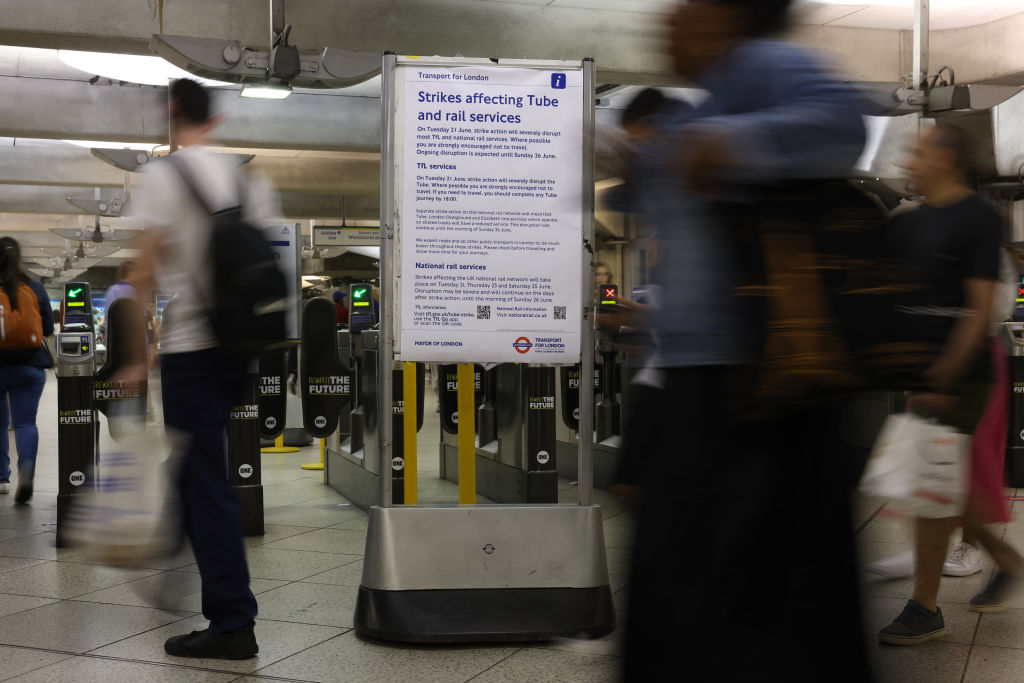

This is certainly the fear of the unions, provoking them to strike this week. But the impact of such strikes are much diminished now many know working from home is possible.

Furthermore, the unions risk playing into the Treasury’s hands. The government is reported to be modelling a future transport system based on 80 per cent of pre-pandemic passenger numbers. If strikes halt the steady week by week increase in numbers of commuters using London’s buses and tubes, the Treasury could cite this as even more evidence to justify shrinking investment in the transport network.

Since the pandemic, it’s been a huge job just keeping buses and tubes running. But how to fund the city’s major capital programme remains unclear. TfL argues it needs government funding for basic upkeep of an ageing system, the rolling programme of upgrades and increased capacity like the Bakerloo Line extension. The government is warning there’s little prospect of money forthcoming – investment must come from within TfL’s own income.

This must surely be a moment to fundamentally reassess how London funds public transport by giving it the freedom to raise more of its own money. There’s an economic argument for this – London knows better than Whitehall what the city needs. Taxes can be better tailored to suit the city’s circumstances, and by strengthening the accountability of the Mayor to the city’s voters, there’s a democratic case in favour too. Finally, the government ought to see the political advantages.

First, it means ministers are less likely to get the blame for when things go wrong – it wouldn’t be so easy for the Mayor to point the finger at the government. And second – it’d end the wrath ministers face from politicians in the north and Midlands when billions are handed over to London.