Consumer price cap: Is the safety net fit for purpose?

“We accept that had we done that earlier, it would have been better for customers.”

These were the words of under-pressure Ofgem boss, Jonathan Brearley, following historic market carnage in the energy sector, and the regulator’s decision to hike household energy bills to an eye-watering £2,000 per year.

Following an intense grilling from MPs, Brearley admitted to the BEIS Committee that Ofgem should have stepped in to deal with the crisis earlier, and that regulation of the energy industry will need to be “tougher”.

He explained Ofgem would have to be “more careful” when establishing the financial resilience of smaller suppliers in the future.

In preparation for this new reality of increased intervention, Ofgem has recently announced plans to introduce hedging controls and financial stress tests for suppliers to prevent energy firms wilting in future market shocks.

This follows intense criticism of poor financial planning from fallen energy firms as the market expanded to a peak of 80 suppliers following liberalising reforms that broke up the Big Six’s 97 per cent stranglehold on the industry.

It also echoes a general theme of rigid protectionism across the country, with Chancellor Rishi Sunak dipping into the public purse once again to create a £9bn state-backed loan scheme to shelter households from rising household bills, with energy users expected to foot the bill for £200 rebates and the expansion of the Warm Home Discount Scheme to three million consumers over the coming years instead.

Where Brearley was less inclined to give ground was on the issue of the consumer price cap itself, the primary discussion point at the Westminster session.

Consumers protected at a heavy price

While the existence of the mechanism is not within Ofgem’s remit, having been passed in the House of Commons as part of the Domestic Gas and Electricity Act in 2018, the chief executive spoke favourably about the state-mandated safety net.

He said the price cap has “protected customers across winter” and made sure they “are paying no more than they need to for their energy.”

This reflects Downing Street thinking, with the Business for Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) defending the value of the safety bet when approached for comment by City A.M.

A BEIS spokesperson said: “The energy price cap has shielded millions of customers from price volatility in wholesale markets and ensured they pay a fair price for their energy. Despite the rising costs of wholesale energy which precipitated the failure of several energy suppliers, Ofgem have kept the cap at the level set in October 2021 over this winter.”

Ofgem is planning to reduce the review period from six to three months, and intervene more quickly in the case of future industry emergencies, but the mechanism otherwise remains untouched.

The cap has sheltered millions of households over recent months from soaring wholesale costs in a market battered by rebounding demand, shortening supplies, and sustained geopolitical volatility, but the costs of clearing up the consequent market carnage have been astonishing.

Alongside Sunak’s latest costly measures, Investec has warned households could be on the hook for £3.2bn, from the on-boarding costs involved in the supplier of last resort process with 26 energy firms ceasing to trade since last September.

Many energy firms have simply been unable to pass a five-fold hike in wholesale costs and record power prices to consumers, while Octopus Energy has revealed that taking on a new customer has resulted in a £700 loss for suppliers during the crisis.

Meanwhile, Bulb Energy (Bulb) fell into special administration last November, and has remained on life-support over winter, being sustained with regular transfusions of public money – with estimates the taxpayer bill could reach £1.8bn.

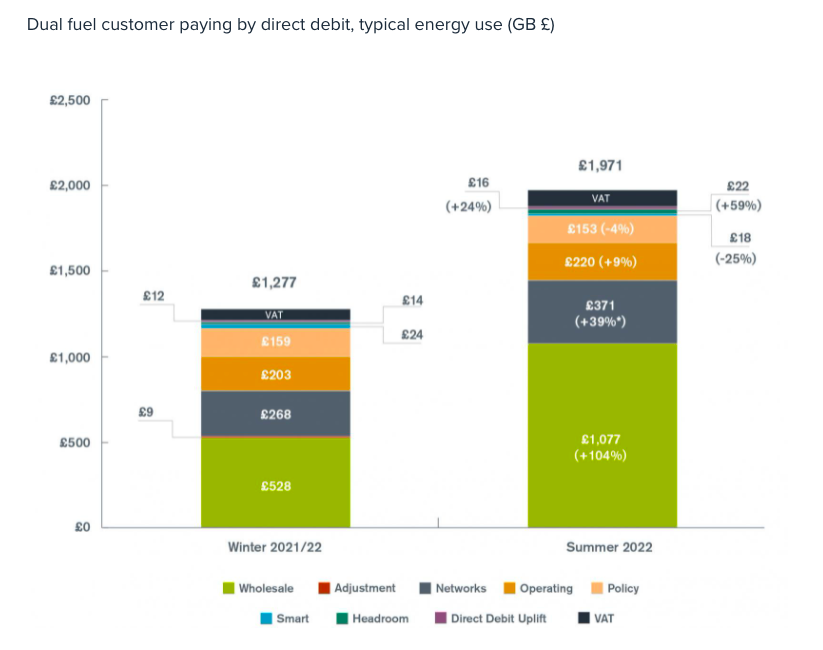

| Time Period | Consumer price cap for average use |

| January 2019 | £1,136 |

| April 2019 | £1,254 |

| October 2019 | £1,179 |

| April 2020 | £1,126 |

| October 2020 | £1,042 |

| April 2021 | £1,138 |

| October 2021 | £1,277 |

| April 2022 | £1,971 |

This would make it the biggest state bailout since RBS in 2008.

Following its fall from grace Bulb revealed soaring wholesale prices meant it cost them £4 per therm to buy energy, but the price cap was limiting what it could charge consumers to 70p per therm – a fundamentally unsustainable model for businesses, regardless of any questions over Bulb’s financial management.

Commenting on the mechanism, Dr Craig Lowrey, senior consultant at Cornwall Insight said: “The cap was never meant to be a permanent solution and today has shown that rather than protecting customers, the impact in the wholesale market over the last 12 months was simply deferred, leading to this significant increase announced today.”

Scottish Power CEO Keith Anderson has also called for the price cap to be reformed in recent months, while John Penrose – the MP who first proposed the cap in the House of Commons – no longer considers it fit for purpose.

Speaking to City A.M. earlier this month, Utilita Energy founder Bill Bullen stressed the need to accept that rising costs in energy bills can’t be mitigated by sweeping measures.

While he felt dealing with Ofgem has been a “revelation” since Brearley’s arrival, with the chief executive open to questions and scrutiny, he also raised questions over the regulator’s experience.

In particular, he criticised the regulator’s initial reaction to the current crisis.

He explained: “There is possibly a bit of naivety in Ofgem. They have all gone up a very steep learning curve. So, while I would really celebrate Jonathan Brearley’s attempts at engaging in this massive change in circumstances, and we have not seen energy prices rise like this in my lifetime, I would also point out that with the October price cap, they were still cutting supply margins. Despite the fact all the suppliers were underwater.”

Industry leaders fear that high gas prices could be baked into the market, with increased wholesale costs a fact of life at least in the medium term.

Emma Pinchbeck, chief executive of trade body, Energy UK, has already warned of a further price hike this October, when household bills could soar over the £2,000 milestone for the first time.

Which raises the fundamental question: what is the point of the price cap if it can’t keep down the costs of energy?