How marketers can use behavioural psychology to change people’s minds

I have often found myself surprised to learn how utterly predictable my behaviour is whenever I read the work of social scientists specialising in behavioural psychology.

Having always prided myself on at least some level of individuality, it’s disappointing when the decisions I feel that I make freely are played back to me as if they were scripted.

Fortunately, I’ve also benefited from such work.

Read more: People-based marketing can unlock a lifetime of value

Creative communications agencies have long used behavioural theory as an input to develop the campaigns that have helped guide our nation’s choices. The government in particular demonstrates best practice in this area, with its campaigns that tackle behaviours such as smoking and dangerous driving.

However, there have been seismic changes in the industry over the past decade, not least in the fragmentation of the media landscape. Rather than broadcast a single message to a mass audience, we are now required to engage whole communities of people through a complex web of channels, knowing they might join – and leave – the narrative at any stage, and may even participate in it themselves.

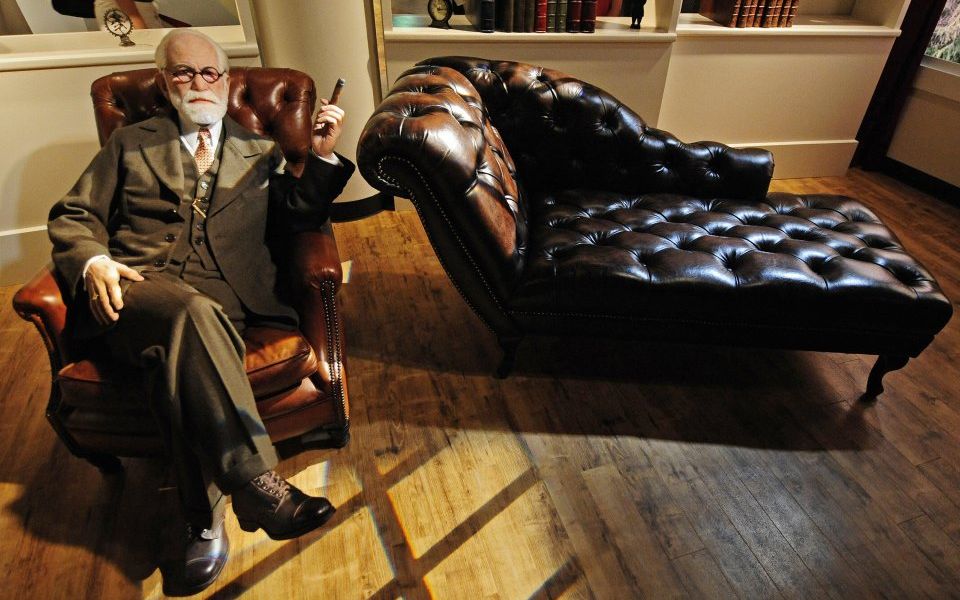

The power of the mind

Using the principles of behavioural theory in such a complex environment is challenging, and it could well be a factor in the declining impact of classic strategies for behaviour change.

At Y&R, we have been working with a fresh approach that appears more suited to this new media landscape. It centres on an emerging field within behavioural science called social practice theory.

What makes this approach so different? Well, existing models of behaviour change tend to regard the individual and their actions as the focus of the intervention.

But social practice theory takes a wider perspective, seeking to understand the socio-cultural conditions in which certain behaviours take place, and make interventions in a more holistic manner.

For example, people don’t set out to eat too much salt – they eat their regular breakfast, and the salt they consume is a direct consequence of that.

Hence, rather than run a campaign encouraging people to limit their salt consumption, social practice might suggest tackling the public’s eating routines and food choices at breakfast time, in order to bring about a reduction in salt intake.

Clever commuting

A real-world example of social practice theory can be seen with the Greater Manchester Cycling Hub programme.

The objective of the scheme was to encourage greener transport in order to reduce pollution.

But rather than simply try and encourage people to cycle with classic approaches such as environmental information or subsidised bike programmes, the social practice of “the commute to work” was specifically considered.

This resulted in Transport for Greater Manchester introducing dedicated cycle parking facilities around key public transport hubs. These included lockers, bike servicing facilities, and showers, because turning up to work sweaty and unclean was a common concern that discouraged commuter cycling.

Safer socialising

We recently worked on a campaign for the Department for Transport to tackle drink-driving, and it was inspired by social practice thinking.

In general, young men (the group most likely to commit this offence) don’t start an evening with the intention to drink and drive. They simply want to have a good night out with their mates.

But the dynamics of their friendship group may be influenced by perceived notions of “masculinity”, which can lead men to behave in a way where they appear more confident than they feel. Coupled with a lack of forward planning, this can result in some young men undertaking the risky behaviour of drink-driving.

The campaign “Mates don’t let mates drink-drive” uses the dynamics of that social group and wider cultural influences to break down those perceived notions of masculinity and encourage men to moderate each other’s behaviour.

Ads for the campaign were viewed by more than seven million young men in the UK, with 60 per cent of those who saw the advert saying they had taken action to stop a friend drink-driving as a result.

At Y&R, we believe that social practice provides a more thorough and holistic perspective on behaviour that is fit for the modern media landscape.

It works as a complement to classic approaches, and we believe that it unlocks new solutions to old problems and can deliver high-impact results.

Our successes on the Department for Transport’s drink-driving campaign are prompting us to embrace the principles of social practice theory more fully, and apply them to a wider range of marketing challenges.

If embraced by the industry more widely, perhaps social practice theory can help us to better demonstrate the commercial returns that marketing can achieve.

Read more: What to do when a robot takes your job?