The big cheese: How old food can sell for crazy prices at auction

It took two hours for bidding to draw to a close, but it was worth it. The 2.62kg Cabrales cheese left the auction tent at the 2018 Cabrales Cheese Competition to rapturous applause.

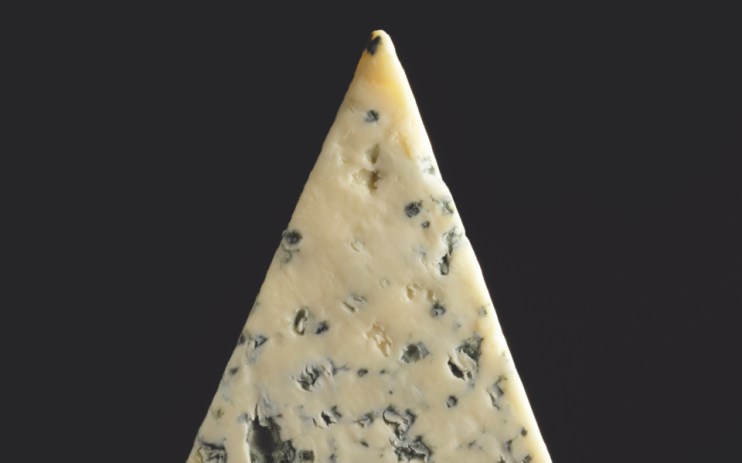

Cream of the crop, the cheese had caught the attention of 15 restaurateurs from around Spain, each bidder hell-bent on blessing their dishes with its distinctive flavour – and, for the handsome fee of €14,300 (about £12,000), it is the most expensive blue cheese ever sold.

As blue cheeses go, Cabrales was attractive. The creation process is arduous: maturation takes six months in the caves of Picos de Europa, a remote mountain range in Northern Spain to which the freshly made cheese must be carried on the backs of shepherds. The result is a rich patina of varicose-like veins, and “a strong, sharp aroma and a slightly acidic taste”.

Its destiny was always fine cuisine, but surely, at such a price, there must have been a reflex to preserve, not portion. After the initial rush, the proud new owner, Iván Suárez of the Llagar de Colloto restaurant in Oviedo, would have faced a fleeting, agonising choice: pepper dishes with the cheese, or keep it intact in the hope that in five or 10 years it would rise in value.

Old foodstuffs have often fetched high prices, particularly if they come with a story. Six years ago Wiltshire auction house Henry Aldridge & Son made headlines for selling a cracker that survived the Titanic. The Spillers & Bakers Pilot cracker, found inside a survival kit attached to one of the lifeboats, was dubbed “the world’s most valuable biscuit” after going to a German collector for $15,000. At a 2001 auction a similar outcome befell a (then) 100 year old chocolate bar retrieved from the Discovery, the ship that transported Captain Scott on his 1901 expedition.

Foods linked to those in living memory also wield power: in August a slice of Charles and Diana’s 1981 wedding cake sold for £1,850. The fruit and marzipan confection is detailed with an intricate rendering of the Windsor coat of arms, preserved for 30 years by the sugar. But what does it mean to buy and sell food, when the value is predicated on not actually eating it?

Rarity and provenance are the buzzwords for these auctions. Be it a rusty bottle of 18th century rum unearthed in a cellar, or a half-eaten hamburger found at the scene of a famous crime, the story enlivens the object, stirring investors’ appetites. But the act of buying a foodstuff at auction, in particular one that you have no intention of actually eating, also speaks to a new kind of conspicuous consumption – of being rich enough that food becomes ornamentation.

Of course, people often bid on food items as a power move. At the 2006 Chinese New Year Gala in London a fortune cookie raised £10,000 pounds. The proceeds went to a children’s charity, though my guess is the winning bidder cared as little for the cookie’s cause as they did the destiny hidden within its folds. Foods such as this are not to be handled, but displayed as a fragile symbol of philanthropy.

Bidding for food has mercantile roots, the selling of both live and deadstock as much a staple in Ancient Greece as it is in many parts of the world today. Edible delicacies sell for big bucks, such as the bluefin tuna in Japan, one of which went for $3.1m in 2019 at the Toyosu wholesale market in Tokyo. On a smaller scale, London’s Smithfield market, in operation since the 12th century, traditionally holds a meat auction on Christmas Eve. In ordinary times more than 1500 attend the event, bidding for cuts with the zeal reminiscent of an 80s trading floor.

Perhaps there’s good to be seen in the counterintuitive inclination to save food for a quarter of a century rather than eating it at its most nutritious. In a way it preservation speaks of how we have grown to value food culturally; a civilisation that has moved beyond the need for constant sustenance, and towards valuing food for its beauty and historical significance.

Though, if I’m ever in Oviedo, you bet I’ll be paying Llagar de Colloto a visit.