How a museum is using NFTs to bring religious art to life

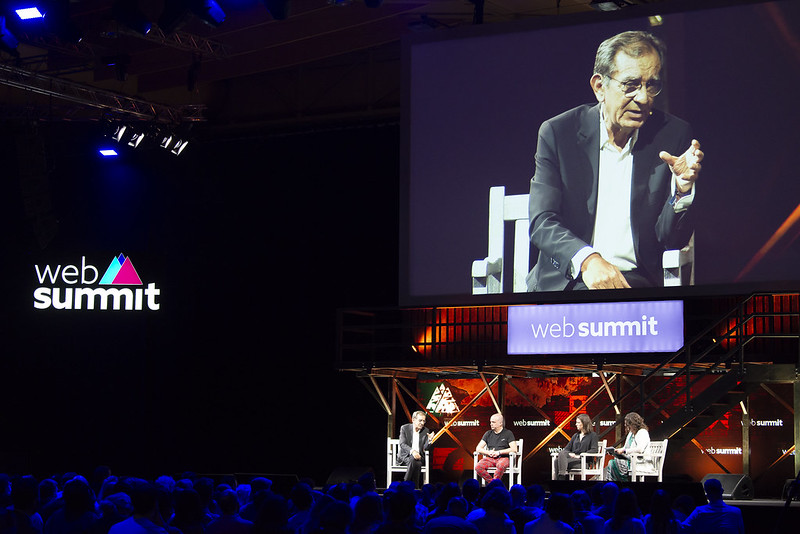

Crypto AM writer Jillian Godsil meets Dr Edmundo Martinho, president of Santa Casa da Misericordia de Lisboa…

Dr Martinho hails from the field of social sciences but spent the first 15 years of his career working in the private sector, reaching the position of general manager of an international pharmaceutical company.

Then, in 1996, Portugal launched a Guaranteed Minimum Income scheme (today known as Social Insertion Income) and the Minister of Labour and Social Security, Ferro Rodrigues, approached him, and indeed challenged him to join the team.

It was a major career shift, but Dr Martinho embraced it with gusto. He also felt the skills learnt in the private sector would stand him in good stead.

“I understood the importance of planning which can sometimes be overlooked in large public bodies,” he says.

“The second set of skill sets is attention to details and being very focused on results.”

Implementing the scheme was a major initiative for the Portuguese Government, tackling both the need for a minimum subsistence income and addressing societal needs through social activation.

Aside from the breadth of the ambition underpinning this policy, because it was so new, the supporting departments required additional experience on how to implement it.

“We had to make sure people could access their new rights. This was a new national strategy to combat poverty, with a special focus on child poverty,” explained Dr Martinho.

“But our struggle was to support families, not just with money, but to support them in their personal and family development. This is still an issue for today.”

Holistic policy

The policy aimed to be holistic and cater for the well-being of the family, and the child within the family.

“From housing to health issues to education – we need to understand that each person is a universe and that the universe is composed of different layers,” he adds.

While Dr Martinho acknowledges this approach may differ from other European policies, he also agrees that it’s not the approach but the capacity to put it into practice that is important.

“Part of the difficulty of implementation lies in the different layers of authorities with responsibility for implementing different elements – from the local authorities to national authorities – and to make sure that everyone moves forward in the right direction.”

Dr Martinho remained in the public sector, working across related welfare departments and holding presidential titles in related commissions, until 2016 when he joined Santa Casa da Misericordia de Lisboa, or SCML, a non-profit organisation overseen by the Ministry of Social Affairs and funded by the revenue of the lottery games in Portugal.

Since 1498, SCML has pursued its original mission – to improve the quality of life of the citizens, by managing all social policies related to children, youth, adults, families and older people, with particular emphasis on population groups who are in difficulties (disability, dependency needs, poverty). Best known for its Social Welfare Work, Santa Casa is also extensively active in the fields of health, education, research, culture and social entrepreneurship, as well as in the development of its considerable property assets, many of which have been bequeathed by benefactors.

It is also responsible for the operation of the state lottery games, thanks to an exclusive concession from the Portuguese State for the whole territory of Portugal. The revenue from the lottery games goes to good causes all around the country.

“SCML is a very important organisation in Portugal in many different ways,” he explains.

“It manages the state social gaming which generates resources which are used to run different social programmes, to support the public purse and to provide resources for other government departments.

“In Lisbon SMCL is the main organization to support those in need, whether the need is material, food, health, housing or refugees. It is up to us to support the city of Lisbon.”

SCML also has a huge historical and cultural significance in Portuguese life, with more than 500 years’ worth of priceless art works, relics and items of sacred importance.

The beautiful artefacts and art are available to view in the SCML museum but also in the Church of Saint Roch (Sao Roque), reputed to be one of the most beautiful churches in Lisbon. The saint for which it is named is also meant to be a protector from the plague.

In fact, next year SCML is to open a new museum called the House of Asia to display the rich collection of Asian art and relics collected over the years. The opening will be a landmark year for the city of Lisbon and Portugal.

“Our main goal is to preserve these assets – and to enrich the collection,” says Dr Martinho.

Part of the enrichment means reaching out to contemporary artists, including graffiti artists and refugees.

“We mix cultural and social significance – looking to support Portuguese artists, people with mental issues, people with disabilities and refugees. These are our main drivers at the moment.”

Despite Saint Roch being a protector against plagues, SCML was doubly impacted by COVID.

Introducing non-fungible tokens

“This first was when we were hit in our resources during the pandemic period as people reduced their gaming significantly. At the same time, we saw an increased pressure in demands for support from citizens,” he explained.

“We had to increase our services to include food support, to provide isolation care accommodation for people with COVID, and a huge increase in home care services.”

There are more than 5,000 employees all dedicated to making better services available and moving the SCML forward as a progressive, future looking organisation, even as it carries its history. Part of this was the adoption of the most modern of developments – non-fungible tokens, or NFTs.

“When I first heard of NFTs I thought this could be a very interesting opportunity. On the one hand we could show off our assets and make them available for everyone who wants to get acquainted with the richness of our museum and the church.

“And on the other hand, we saw the possibilities of increasing revenues for the SCML through the new platform we are launching.”

While Dr Martinho understands the SCML is one of the first museums to embrace this technology, he also believes that many others will follow suit, that is it the future of museums if they wish to stay relevant.

“Already we have received approaches from other museums asking for our advice on how they might do something similar. It is a learning experience, and being one of the first means we are not guaranteed initial success, but it is a unique opportunity to remain relevant, display our treasures and look to earn new revenue.”

Dr Martinho knows that for a museum to stay alive and relevant, it cannot sit still.

“We have to move ahead if we wish to survive.”