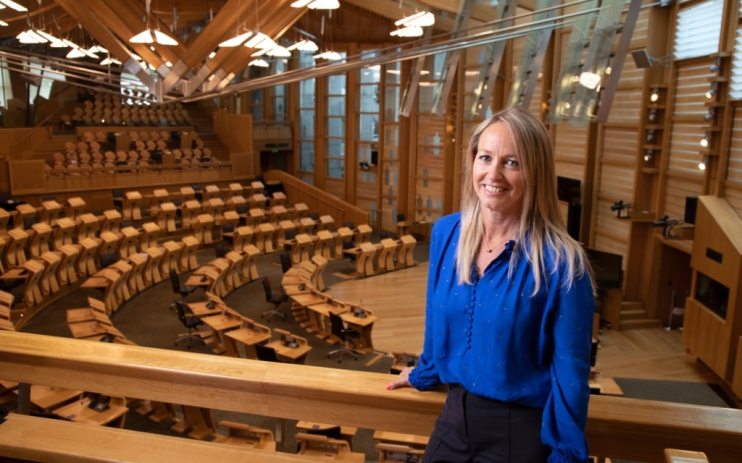

Sara Glass CA: From the private sector to CFO of the Scottish Parliament

This article first appeared in ICAS’ CA magazine.

Sara Glass CA left a successful career in the private sector to become CFO of the Scottish Parliament. She tells Ryan Herman why the two roles are more similar than they appear.

It is less than a year since Sara Glass CA became Chief Financial Officer for the Scottish Parliament. During that time there’s been an election, a high-profile inquiry into the government’s handling of harassment complaints, and new working practices and reallocated budgets, courtesy of Covid-19. And all the while the question of a second independence referendum hums away in the background. During extraordinary times, one needs a steady hand on the tiller; people who can make calm, non-partisan decisions. People like Glass.

The story starts more than two decades ago, when the Scotland Act of 1998 included the founding of the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body (SPCB) – effectively a board of directors. It is currently made up of representatives from the major political parties in Scotland and is responsible for managing the Parliament’s budget, property, staff and resources.

“The SPCB is independent of the Scottish government and that’s who we report to,” says Glass. “We have four values – stewardship, excellence, respect and inclusiveness – and while all four are embedded into the job of CFO, excellence and stewardship are at the core of my role. It means focusing on the long term, so we leave things better than when we found them. We put our shared interests ahead of any individual or team to enhance our reputation through everything we do to deliver high-quality sustainable results.”

One of her first actions was to recommend that all MSPs should have a pay freeze. “Last November we were setting the budget for the year,” she explains. “We have indices in place to calculate salary increases and that sort of thing. The ASHE index [Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings] is used for salaries, and it moves about year to year. It had been really low for the preceding four or five years. But it was at a level [an automatically linked 5.1% pay increase] that didn’t feel comfortable at a time when people were on furlough.

“We knew that the UK Chancellor was about to implement a public sector pay freeze for England. In Scotland, there was an expectation of public sector restraint, outside of the NHS. My role was to make that recommendation to the corporate body. That was taken to Parliament, which voted to agree on a freeze for the upcoming year.”

This awareness of public expectation is a key change from Glass’s last job, as Head of Global Finance Capability for the drinks giant Heineken, where she was accountable to her employer and its shareholders. “What makes this feel different to any previous role is that heightened sense of responsibility,” she says. “The people of Scotland are your key stakeholder. You are acutely aware of where the money is not going – for example on the NHS – if we’re spending it. But, in many other ways, this is not so different from a corporate environment, where you have consumers, and you still have to do things in a financially responsible way.

“For my last job in the UK I was the Head of Finance for a supply chain, and I was looking after a budget of £750m. So, the scale is different with this job. And there’s also the fact that anyone could put in a freedom of information request. Knowing everything is scrutinised all the time brings quite a different dynamic than working for a multinational. In the world I’m in now, we seek to publish as much as we can. Transparency is at the front of everyone’s mind.”

The fundamentals of the job, though, remain the same: “The CFO role has more similarities than differences to an equivalent in the private sector. Business partnering, leading and developing the team, driving excellence in our processes and ensuring a strong financial control environment are things that are probably consistent across all CFO roles.

“And when I think about what it means to be a CA, the one thing that really sticks with me from those early years of training is a commitment to professional integrity. It becomes part of your DNA. That will stand you in good stead when you face a challenge, in whatever environment you’re working in, when you can say ‘No, my judgement is absolutely clear.’”

Trading places

Glass came into the drinks industry with Scottish & Newcastle breweries in 1999. “I was in my twenties and it was a fun environment to work in,” she recalls. “The company had brilliant brands and lots of great people worked there. There was also lots of change happening during that time – loads of industry consolidation, buyouts and mergers. Heineken bought Scottish & Newcastle in 2008 just as I’d gone on maternity leave. When I went back, I had a new boss, the FD had been replaced and the building had turned green! But it was an opportunity to learn. The way we worked became a lot more sophisticated.”

She went on to work on Heineken’s expansion into Africa: “We were investing in a greenfield site in Ethiopia, but we were also supporting small markets, such as Burundi, that don’t have access to the same quality of staff. There was a massively diverse range of businesses within that region. It was really full-on.

“I left because I had a family, and after seven years of commuting to Amsterdam, it felt like it was the right time to move on. But I did not anticipate that I would be going into the public sector.”

The chance to work for the Scottish Parliament, being at the heart of the national agenda, was simply too good to ignore. “If you take your news from a paper, or via Twitter or whatever, there’s always something about MSPs or the Parliament,” she says. “The building, and everything that comes with it, is just so iconic. Who wouldn’t want to work here? We’ve got three ICAS members [in the financial team], all highly respected. They’ve been there, done it. Being so high profile, and so absolutely relevant, helps us to attract talent that may otherwise look at staying in the private sector.”

CAs often bring a wealth of skills that stretch far beyond the spreadsheet. This is how Glass sees her role developing – as an opportunity to bring about change. The pandemic has meant having to concentrate more than usual on the short term, reallocating funds to make the working environment more Covid-secure. But the focus is now on the future.

“Barring any changes, we want to establish a more medium-term financial plan across the whole organisation,” she explains. “I see chances for us to add more value, rather than being a means to an end, and actually shape some of their thinking. So already that’s something we can see as a good thing to move forward, to heighten the awareness and understanding of what we can do and where we can help.

“If finance is always the department that does things in the background you tend not to educate the organisation – it’s like some sort of black magic going on somewhere else. For example, assumption-based forecasting is something we in finance take for granted, but may not be common terminology for some of our business colleagues who we partner to help form those assumptions. We need to be part of the discussion to give that advice in the first place. It’s not that it’s not happening, but if we want to get to a place where we can do more medium-term planning it is essential.”

Despite all the challenges of the past 10 months, it is abundantly clear that Glass relishes her new role and the opportunity to play a part in shaping the future of the Parliament, in whatever direction it goes. “I never had a plan,” she says, “but I like to be in an environment where I can be stretched and know that I’m leading change and improvement. And I love developing teams. If I’m in a space where that’s happening then I’m happy.”