Red faces full of port wine: how to drink England’s favourite wine

What’s the first thing you think of when you read the word “port”? I suspect for many of you it will evoke a very distinct stereotype, and not all of that will be positive. Some of you, I’ll wager, thought “gout”. Most of the images that came to mind will have been of well-off, well-upholstered men, possibly with the red faces of Betjeman’s poem, enjoying a sweet, syrupy swallow after a hearty meal.

Our relationship with the fortified wine of the Douro valley goes back a long way. In 1703, with England locked in hostilities with France, the Metheun Treaty signed with Portugal allowed that country’s wines to be imported at a very low duty. Supplies from France were limited, so the Portuguese alternative, fortified to help it survive the longer sea voyage to English harbours, rapidly became a popular choice.

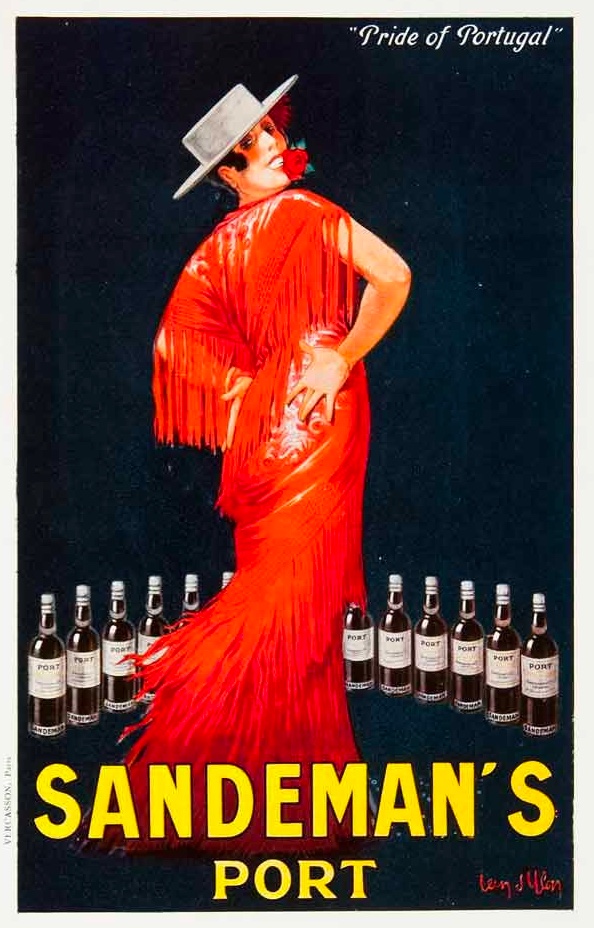

The depth and extent of the English involvement in the port trade can be seen in the names of the great shippers of Porto: Taylor, Warre, Graham, Croft, Dow, Cockburn, Sandeman. Although there were German and Dutch traders too, it was the English who dominated and took up residence to become the fabled Anglo-Portuguese families still in control. And port has become intertwined with distinctively English, or British, customs: the formal dinner, the withdrawal to the combination room, the ceremony of decanters and cigars and walnuts and (for the boldly retro) port tongs. It is a drink ideal for those who like ceremony, display and gadgets.

In this arena, port is a very desirable product. The thick, heavy richness of its flavour is complex enough to stand alone, but it is also a classic pairing with cheese, whether a burly, pungent Cheddar or a soft, creamy Brie. And the cheese course (eaten after pudding in this country, not hemmed in by other courses à la mode française) is a perfect concatenation of flavours and textures to which I shall return in a future column. Port also has the strength, like spirits, to withstand a partnership with tobacco smoke. A Honduran Corojo or a bowlful of Gold Block will echo the sweetness of port to perfection, and help the meditative digestion of a good meal.

Port makers understand, however, that ruddy-cheeked plutocrats and pampered academics are not a sufficiently lucrative demographic that they can rest easy. In particular the gender profile of port is troubling for those focused on growth. I recently spoke to Adrian Bridge, CEO of Taylor’s Port and the Fladgate Partnership. He talked about expanding the appeal of his products, and pointed especially to Croft Pink, the first rosé port developed in the late 2000s and which is aimed at a younger, more female market. It is sold to be drunk over ice, or used as a base for cocktails.

White port is another area with which many consumers are unfamiliar. Chilled, it veers closer to a pale sherry than its heavier ruby cousins, ideal with salty almonds or manzanilla olives. In Portugal it is often topped up with tonic water as a Porto tónico to slake the thirst the climate induces. A cool, refreshing drink? Not what we typically imagine in port, but huge and still largely untapped markets for the mavens of Vila Nova de Gaia.

One of the secret weapons of port is that it can be luxuriously expensive or pleasingly affordable. A respectable late-bottled vintage from the knockout 2011 harvest can be had for £25—laughably good value at a table of six diners—but those seeking the thrill of a higher spend could choose a magnum of the outstanding Dow’s 1977 and receive little change from £300. Importantly, each will be a good, well-made product: it is merely a matter of degree.

Whole books could be, indeed, have been written on port. Richard Mayson’s Port and the Douro is a brilliant history-cum-users’-guide, and Ben Howkins’ Rich, Rare and Red is a first-class atlas to the world of Porto’s finest. You do not need to know even five per cent of this to enjoy a glass of fortified wine, but the rich lore and legend awaits you if ever you want it.

Port is an extraordinarily varied drink. Its makers want it to break out of its traditional high-table enclave and reach new customers: young creatives who don’t even own a tie that they can refuse to wear, female drinkers who feel restricted by the conventional offerings of white wine or fizz, sun worshippers celebrating the ebb tide of the pandemic and the reopening of pubs and bars. For me, the great joy is that there’s room for us all. My heavy ship’s decanter still has some of the Taylor’s 1997 from a recent indulgent dinner (alas I no longer drink, but I delight in others doing so), but a bright and spritzy tónico might be just what you need when the next bank holiday comes around. We’re a diverse bunch, but let us learn from each other and enjoy the fruits of a small corner of Portugal.