Treasury tremors: how does the current sell-off compare with past episodes?

US Treasuries have seen the second worst start to a year and third worst quarter in 50 years.

It is another eye-catching development amid what have been extreme conditions in markets and the economy over the past year.

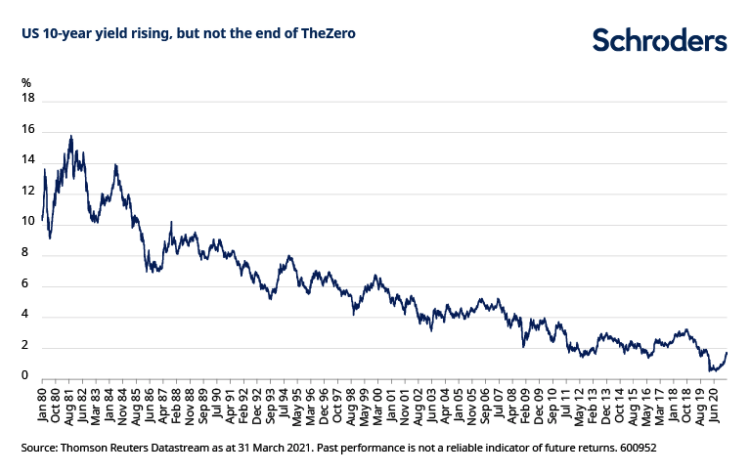

Bond markets have seen particularly unusual circumstances, with yields falling ever lower and an increasing number of bonds trading with negative yields. This effectively means investors pay the borrower to lend them money, guaranteeing a loss.

At present, some 20% of all bonds globally yield less than zero. Almost unthinkably, US Treasury yields came close to this in 2020.

This has led to some to wonder whether these ultra-low yields would become a permanent fixture. The recent rise in US Treasury yields calls this into question. Here we compare the sell-off to past episodes and consider where we may be heading next.

What just happened?

The US 10-year yield rose from 0.91% to 1.72% in the first quarter (Q1) of 2021, reflecting expectations of rising growth, inflation and interest rates. Inflation is anathema to bond investors because it erodes the real value (value with inflation taken into consideration) of the debt since prices are rising, but the value of the debt is not. It might also lead to higher interest rates.

A bond with a 1% yield, with interest rates at 0.25%, is less attractive if rates go to 0.5%. The risk is the same, but the compensation is reduced.

The last quarter’s move returned yields to levels last seen in January 2020. Back then, bond yields started falling, rather than rising, as investors turned fearful and bought bonds amid the first concerns over the pandemic.

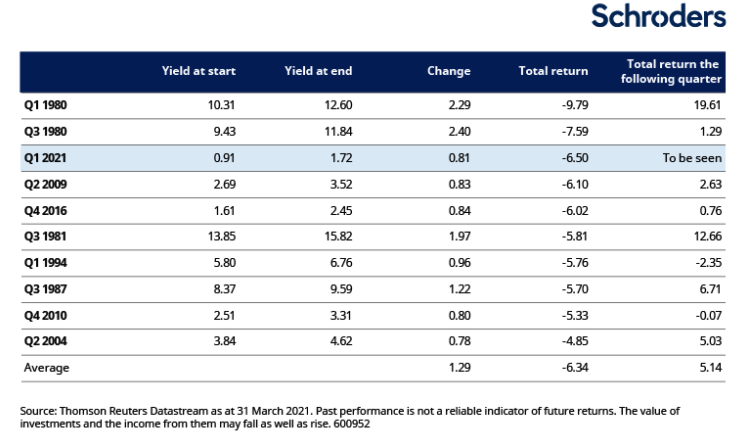

As bond yields and prices move inversely of each other, the return over Q1 for the US 10-year Treasury benchmark was -6.5%.

This decline is second only to Q1 1980, when the US 10-year Treasury yield rose from 10.31% to 12.60%, resulting in a return of -9.8%. This period was the last time we saw double-digit inflation and interest rates, conditions difficult to imagine today.

Top 10 worst quarters for US Treasuries

Bond yields tend to reflect the market’s view of where the economy, inflation (rate of price increases) and, by extension, interest rates might be going. Currently we are seeing an upswell in economic optimism amid the rollout of vaccines, and expectations of a multi-trillion dollar fiscal boost from the US’ newly-elected Democrat government.

Other factors are also at play. The impact of Covid-19 and large scale purchasing of Treasuries by the Federal Reserve (Fed) pushed US yields to extreme lows in 2020. Some reversion from the historic lows was probably unsurprising as investors will have begun to think the market had gone too far. Added to which was the promise of some normalisation emerging.

Lastly, the US will continue to issue significant amounts of new Treasuries in 2021 to ensure it can meet spending needs, particularly with the planned increase in infrastructure investment. There will be more 10-year bond issuance this year too. This allows scope for investors to demand a higher level of interest, lending money for longer entails more risk. Levels of investor appetite will be key. Late-February saw yields lurch higher as a 7-year Treasury auction drew lacklustre demand.

More questionably, the market also sees interest rates potentially rising before 2023. The Fed maintains this will not happen, while it is also more tolerant of inflation.

There is also the technical aspect, namely duration, which is the sensitivity of bond prices to changes in yields. As yields fall, duration rises, and the lower yields fall the more sensitive prices become to changes in yields. So although the yield rose by the same amount in Q1 2021 as in Q2 2009 and Q4 2016 (see table), the decline in returns was bigger.

This works the other way too. As an indication, if half of the recent 10-year yield rise reversed, with duration at about 9.4 (the Q1 average, according to Datastream), this would result in a return of over 3.5% (9.4 times 0.4).

Discover more from Schroders:

– Learn: What 175 years of data tell us about house price affordability in the UK

– Read: The equity sectors best at combating higher inflation

– Watch: The telecoms business which pioneered a payment system lifting thousands out of poverty

How does this sell off compare to history?

As the table shows, the 1980s was especially volatile for US Treasuries and a stark demonstration of how damaging runaway inflation and big swings in interest rates can be for bond returns. Inflation rose from 6% to almost 15% from 1978 to 1980. Paul Volcker became chair of the Federal Reserve in August 1979 with interest rates at 11%. By March 1980 rates were 17%.

The US went into recession and rates were slashed to 9%. Inflation stayed high, however, resulting in further rate hikes. Rates peaked at over 19% in January and June-July 1981.

The sell offs in 2009 and 2016 were more comparable to today’s. 2009 reflected the post-2008 recovery and 2016 reflected rising inflation expectations after the election of Donald Trump and announcement of economic stimulus.

The 1980s saw some impressive quarterly rebounds from US Treasuries, but overall their propensity to bounce back has been mixed. In the most recent episodes, it has taken longer to recover losses. We could well see Treasury yields consolidate at this higher level, but with ongoing fluctuations.

Will volatility continue?

2020’s extreme lows, underpinned by policy measures, caused some to wonder whether bonds could ever again be an attractive source of income. The Fed could move to limit the rise in yields, but there is scope for the market to remain more lively, which could be good for active investors.

“While the short term argues for higher yields, the longer-term structural drivers of “lower for longer” remain in place. Any move towards 2% yields in 10-year Treasuries would start to look like good value,” said Neil Sutherland, US fixed income portfolio manager.

“Structural impediments to higher yields remain in place, not least the highest global debt burdens since World War II and muted prospects for rising wages. $13 trillion of bonds globally still have negative yields so there is a limit to how much US yields can rise. If higher yields start to impact financial conditions, the Fed has a ways to cap the rise. The amount of debt in the US and global economy means it cannot function with significantly higher bond yields.”

Topics:

– For more visit Schroders insights and follow Schroders on twitter.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.