What wicked rugs we weave: Anni Albers at the Tate Modern is a retrospective of modernism’s forgotten pioneer

Born in Berlin in 1899, Anni Albers was a pioneer of the textile art movement. A weaver, designer, writer and printmaker, she trained at the Bauhaus, where she explored the possibilities of bringing weaving into the modernist project. She later became a teacher at the legendary Black Mountain College, where her work sought to redefine how fabrics were used, and to establish thread and weaving as a legitimate art form rather than something you tred on without a second thought.

It wasn’t always her goal. She originally wanted to paint, and writes that she took up weaving “unenthusiastically, as merely the least objectionable choice” before the medium grabbed her imagination. That was in 1922, but her apathy towards tapestry is one still felt by most audiences today. Albers’ contributions to the modernist movement have been largely overlooked by modern galleries, as evidenced by this Tate Modern exhibition being the first major retrospective of her work in the UK.

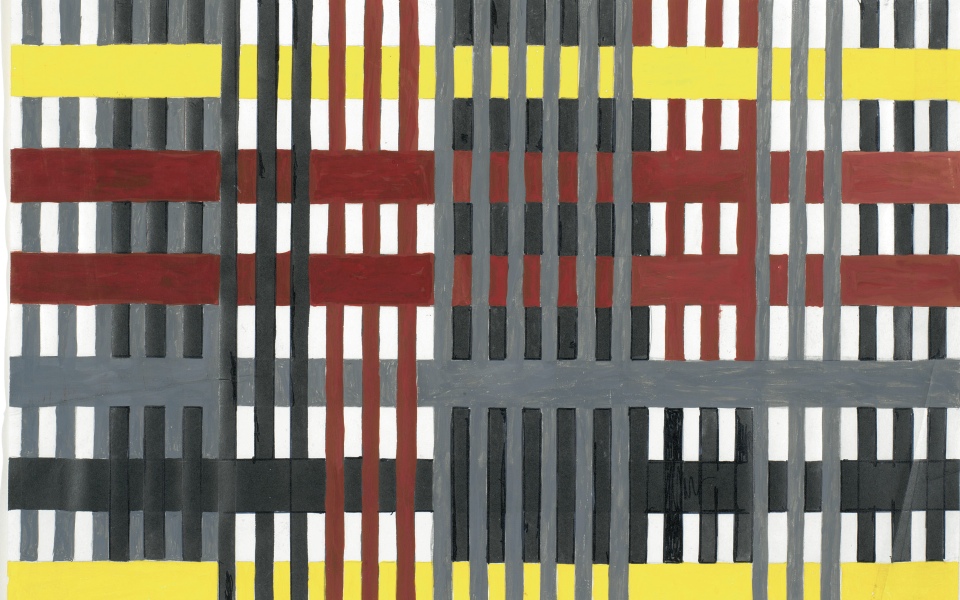

There’s a physical limitation to the medium of weaving, a restricted vocabulary that makes a gallery of pieces quickly look similar, repetitive, even boring. It’s perhaps this restriction that turns so many, including the young Albers, away from textile art, but proceeding through the gallery reveals that it’s the bending of these same limits that defines each piece.

Basic grids and blocks of colour are reminiscent of modernist painting, but more striking is when the meticulous interlacing of threads and materials create illusory new hues and shining textures. A weaving of three threads can create a pattern of six or more colours, like primitive computers placing pixels side by side to overcome a restricted palette.

Later rooms deal with Alber’s studies of the art of pre-Colombian cultures, whose ancient fabrics are also on show here. But her masterpiece is truly striking. A six-panel work titled Six Prayers, it stands both as a memorial to the six million Jews who died in the Holocaust, and as testament to the idea of weaving as a valid art form, deserving of recognition.