Culture in the age of Trump: His legacy in theatre, art and film

Tomorrow marks the inauspicious end to one of the most divisive and controversial Presidencies in American history. Trump’s four-year legacy includes a partially-built wall, the dismantling of decades worth of environmental legislation, and a record-setting second impeachment. But he also had a huge influence over the world of art and culture, with creators across the world responding to his unique brand of populist politics.

With its relatively nimble production schedule, theatre writers and directors were among the first to examine the Trump years, especially through the timeless prism of Shakespeare.

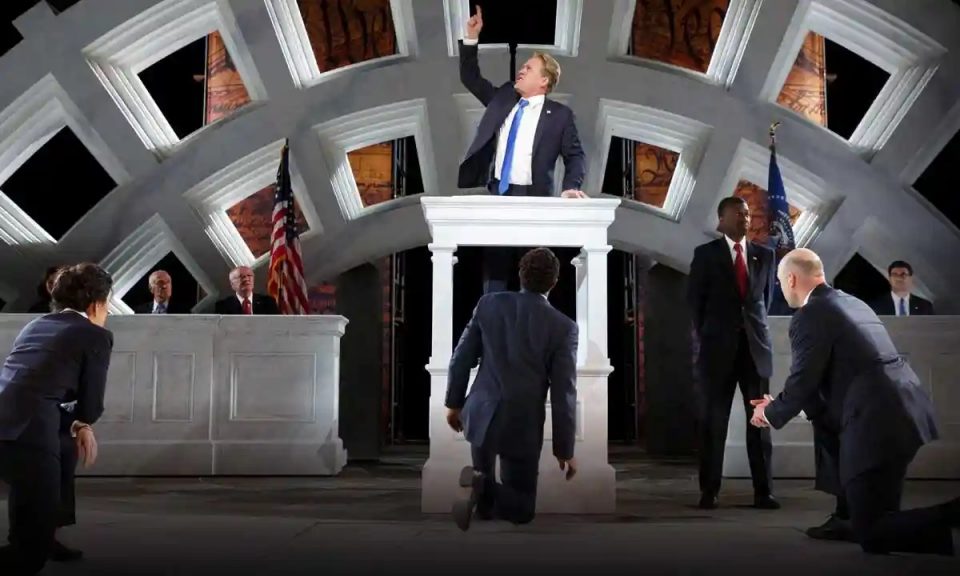

With their universal themes of pride and corruption, theatreland’s Shakespeare aficionados gleefully riffed on Donald Trump, with actors hamming up the President’s already hammy delivery. One of the more overt references came in Nicholas Hytner’s blistering Julius Caesar at Bridge Theatre, in which the play’s ageing demagogue wears the now depressingly familiar dark suit and long, red tie. Moreover, the play began with a rally, the audience standing amid a boorish crowd of jeering political acolytes wearing red “Caesar” caps (which were available to buy).

Ivanka Vacuuming at Flashpoint Gallery

Hope to Nope at the Design Museum

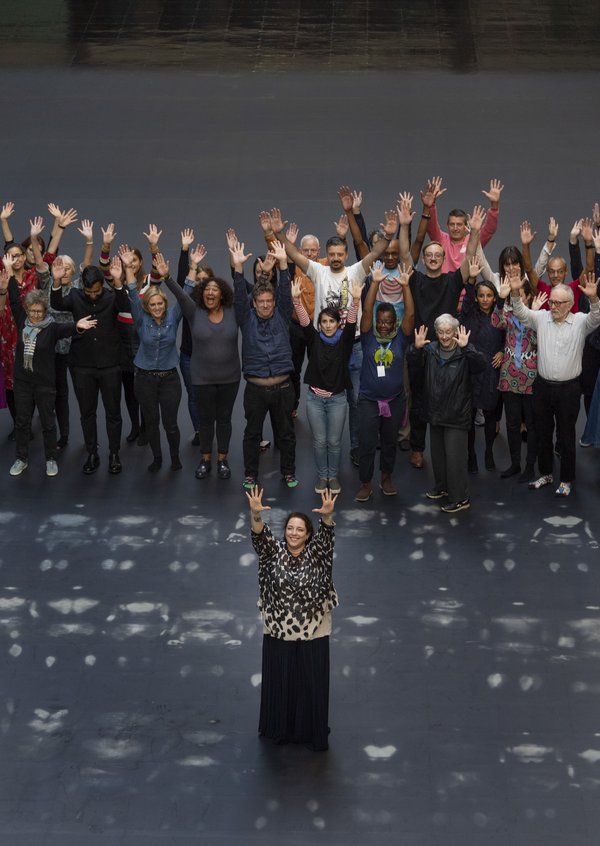

Tania Brugueraat the Tate Modern, 2018

Buried Child at Trafalgar Studios

Julius Caesar performed for Shakespeare in the Park in New York

Julius Caesar at Bridge Theatre

Shipwreck at the Almeida

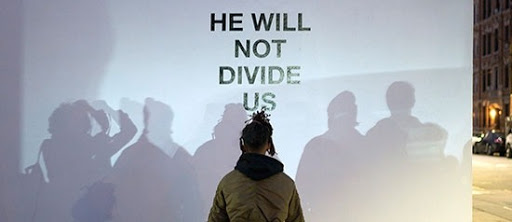

HeWillNotDivideUs at the Museum of the Moving Image

BlacKKKlansman

Parasite

The Purge: Election Year

Two Ladies at Bridge Theatre

Roma

This came a few months after funding was pulled from a production of the same play in New York. Audiences lapped up the satire of Trump’s strangely effete gesticulations but the scene in which the Caesar – and by proxy Trump – is assassinated proved too much, with death threats pouring in and the controversy gleefully stoked by right wing media outlets.

The Almeida, with its propensity to push the envelope as far as envelopes can reasonably be pushed, took depictions of Trump to a whole new level in Shipwreck, a fractured, meandering, three hour play that explicitly examines the landscape that led to his election. The narrative hinges on a single, demonstrable lie told by Trump during the primaries, since largely forgotten: that he petitioned against the Iraq war so strongly that George W Bush sent a delegation from the White House to ask him to “cool it”. This leads into an imagined meeting between the two men in which an erudite Trump physically and intellectually dominates the witless Dubya.

A later fantasy imagines the infamous meeting between Trump and former FBI director James Comey, an exchange in which the President is portrayed as a Caligula-esque demagogue, spray-painted gold and clad in a pair of red trunks, which is one of the more pungent images to emerge in the last four years.

The Bridge theatre’s 2019 play Two Ladies took a different tack, focusing on a meeting between fictionalised versions of First Lady Melania Trump and her French counterpart Bridget Macron. It examines the women who stand beside the president, with Croatian-born Sophia’s picture of manicured elegance masking an inscrutable darkness.

Trafalgar Studios excellent production of Sam Shepherd’s excellent play Buried Child was quick to react to the sense of despair that set in the aftermath of the Trump Presidency. Opening in December 2016, it was impossible to extricate the play’s themes of entropy and despair among the disillusioned white working class from the political drama playing out in the White House.

Hollywood was less quick to overtly capitalise on the Trump years, perhaps owing to the many millions in funding required and the fact you’re almost sure to alienate half of your paying audience. The films that best captured Trump’s divisive energy instead drilled into the causes of alienation and disenfranchisement – Parasite with its exploration of the sometimes-violent consequences of poverty; Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, which humanised exactly the type of Mexican family that Trump was railing against in his speeches; BlaKKKlansman with its battlecry against resurgent white nationalism.

Other films seem remarkably prescient with the benefit of hindsight. The Purge: Election Year was released in August 2016, just as the Trump election campaign was going into overdrive. It tells the story of a world in which a populist government has legalised crime for one night, leading to groups of frenzied militia stalking the streets acting out their violent fantasies, something that now seems to have foreshadowed the storming of the Capitol building this month.

The reaction to Trump by contemporary artists has perhaps been hampered by the pandemic, which has closed institutions across the world. But many had already spoken before then. Tania Bruguera’s installation at the Tate Modern, for instance, highlighted the plight of the world’s migrants and refugees, emphasising the need for people to come together in the face of hate.

The Design Museum’s 2018 exhibition Hope to Nope looked at the evolving nature of political messaging, touching upon MAGA, Occupy, Black Lives Matter, Anonymous, The Arab Spring and Vote.Leave. It looked at ways traditional political messaging had become subverted or superseded by a more viral, grass-roots approach to communication, and how that played into the hands of Donald Trump.

Over in Washington, artist Jennifer Rubell hired a lookalike Trump’s daughter Ivanka to vacuum the Flashpoint art gallery wearing stilettos and the pale pink dress Ivanka wore at 2017’s G20 summit. The piece was inspired by a quote from her mother, Ivana, who had said legal immigrants were welcome in the US because people needed their floors vacuuming.

Actor-cum-artist Shia LaBeouf ran into problems with his installation piece at the Museum of the Moving Image. He had set up a camera and invited visitors to record the words “He will not divide us” – inevitably the piece was soon mobbed by pro-Trump trolls and removed by the museum.

Something in me feels that LaBeouf failed attempt to inspire unity best sums up the last four years: an well-intentioned leftie elitist inadvertently alienating a whole bunch of people; a newly-empowered white working class causing havoc; the whole charade being brought to an ignominious halt leaving nothing but anger and recriminations. Let’s hope President Biden inspires far less art.