Serena’s coach: Tennis is long, slow and too clean

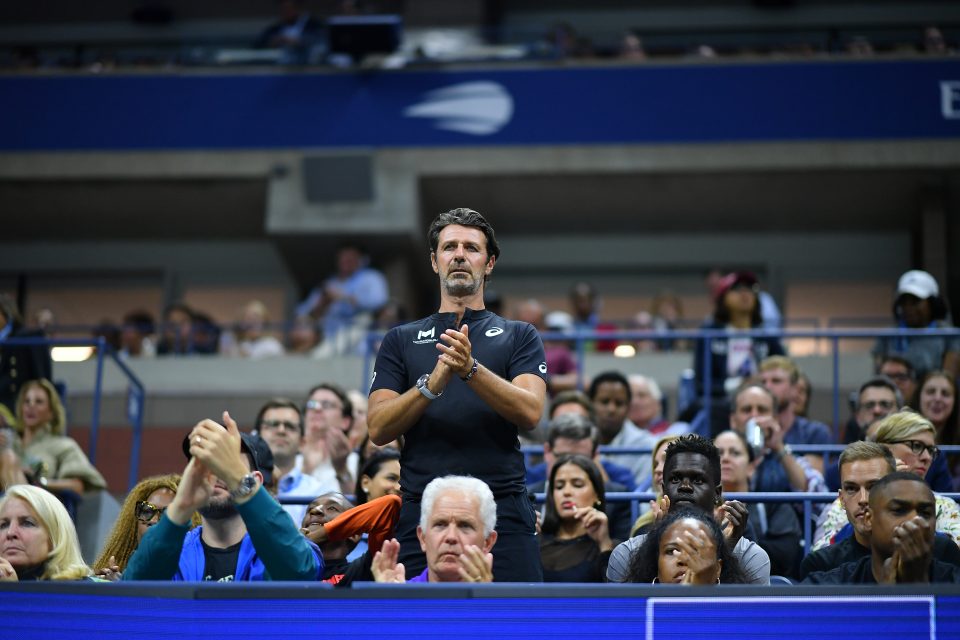

Tennis may have virtually ground to a halt this year, but one of the world’s most celebrated coaches, Patrick Mouratoglou, has rarely been busier.

Mouratoglou, like his clients Serena Williams, Coco Gauff and Stefanos Tsitsipas, has had to adjust to life without much of the usual circuit.

His academy on the French Riviera also suffered amid the pandemic, despite swiftly pivoting to online classes.

But the unscheduled interruption also presented a unique opportunity: to realise his vision for a new series of radically different tennis tournaments.

“We worked 15 hours a day, seven days a week for four months,” he tells City A.M.

“In March in France we were all in confinement at home. I told my team that this was a tough situation. It was going to be extremely difficult for all companies.

“A lot of them are going to be bankrupt. A few of them will find a way to be better than before, and I want us to be like that. So that’s how the idea came out.”

What is Ultimate Tennis Showdown?

Frustrated at the sanitised product elite tennis has become, Mouratoglou saw his chance to launch a shorter, livelier format aimed at a younger audience.

In Ultimate Tennis Showdown (UTS), matches are split into 10-minute quarters and feature wild cards that allow players to steal serves or treble their points.

Players are given cartoonish nicknames like “The Tornado” and “The Sniper”, encouraged to get angry on court and take part in interviews at the changeover.

Mouratoglou staged UTS1 at his academy in June — without spectators, for obvious health reasons — featuring five of the men’s top 10, including Tsitsipas, aka “The Greek God”.

Two more tournaments have followed in the same fashion, most recently in October and won by Australian Alex “The Demon” De Minaur.

“I’m very happy because we created a whole new concept from scratch,” Mouratoglou says.

“In a few weeks we were broadcast in more than 100 countries all over the world on big channels. We launched also an OTT [live-streaming] platform where we showed all the matches, again from scratch.

“In theory it’s one thing but in practice it happened to be really fun. We’re still working on the concept to make it be the best possible, but it worked.”

Mouratoglou is particularly pleased at the players’ feedback. Some who competed in the first event requested to be part of UTS2, he says.

The Frenchman, 50, believes that is at least partly because they were encouraged to show a different side of themselves.

“I think that’s part of the fun,” he says. “They were able to express all kinds of emotions, positive and negative. But we are humans and we all have positive and negative emotions. It’s OK to share them.”

‘Tennis has killed the show’

Mouratoglou caused a stir earlier this year when he called elite tennis “fake”, adding that he was “seriously worried” for the sport’s survival if it didn’t adapt.

“I realise that saying it’s fake is very aggressive but what I mean is players are scared to show their real selves, which is a bit sad. Because that’s what’s interesting — the real people. The fake people are not so interesting.

“I think the tennis show is too long. And most of the pros I spoke to told me they don’t watch tennis at all. I say ‘why?. They say: ‘It’s too long. We watch highlights but we cannot watch matches.’ Because they’re young.

“If you offer a very long, slow and not dynamic show, the younger audience will not watch. And that’s what is happening. We need action, we need emotion, we need personalities.

“That’s what we had in tennis in the ‘70s and ‘80s. I remember really well McEnroe, Connors and Borg. You had such strong personalities and so many things were happening on a tennis court. It was not only two guys hitting a tennis ball. There was a story.

“Because it’s probably a very traditional sport, we went in a direction of becoming as clean as possible. So everybody has to behave perfectly. Nobody can say anything wrong. If you say anything about anyone who’s untouchable, then you’re killed the second after.

“By doing that you kill the show, because you kill the personalities. Players are scared to be themselves. They tell me. A lot of them tell me ‘we feel so good on the court when we are allowed to do what we want, to behave how we feel like’.

“Everybody told me: ‘It’s impossible to do an interview at the changeover’. I said: ‘I don’t think it is’. We did it, and not one of the guys complained. They were happy to do it. Because they felt free and they felt like we were interested in them.”

UTS seeks investors for next phase

Mouratoglou insists UTS is not in competition with the main tours and Grand Slam events.

“It’s a plus, an extra,” he says. “Of course you can be a fan of both, but we’re aiming at a different audience. And it’s going to grow the pie for everyone.

“I said it from day one: I have absolutely no problem for this league to be under the umbrella of the ATP or WTA. For me, it’s to go with, not to go against.”

UTS relies on a typical business model for live sport — rights, sponsorship and ticketing — although the latter is currently absent.

While traditional broadcasters are on board, the plan is for live-streaming via the UTS website to become a bigger part of the business.

Mouratoglou and partners including Alex Popyrin, father of Australian tennis player Alexei Popyrin, are currently fundraising.

“We are working on a capital raise at the moment,” he says. “We want to have a few — not too many, but a few — investors to bring the cash to keep developing the concept.”

They plan further UTS tournaments in 2021 but want to draw up a schedule for the full year rather than take it event by event.

“Now we have a proof of concept, which was the goal,” he says. “We have feedback, we have data. We have a lot of information that I think makes this concept interesting business-wise.”

How to spot a future champion

Apart from anything else, UTS has given players affected by coronavirus-related cancellations a taste of what they have been missing.

“I think the most difficult thing for the players this year was not to know if they would even be able to compete. I think it affected a lot the practice,” he says.

“Tennis players are used to always having a short-term goal, which is the next tournament. And in this case they stayed eight months without having this goal.”

Mouratoglou’s insight into the tennis player’s psyche is based on 15 years as a coach, initially with Cypriot Marcos Baghdatis.

He is best known for his ongoing alliance with Serena Williams, who has won 10 of her 23 Grand Slams since they teamed up in 2012.

More recently he has helped wunderkind Gauff, 16, blossom and Tsitsipas, 22, emerge as one of the men’s game’s most exciting players.

He can afford to be selective about his clients and, unquestionably, knows how to pick a winner.

“I don’t look at the tennis so much. I look at the two or three things that for me make the difference,” he says.

“The first thing that makes the difference in the long term is mentality. Because I’ve been lucky to work with a lot of champions I know that they think different.

“The second thing is competitiveness. Some players are No1 in practice but not good when they play matches. Others, you put on a tennis court and suddenly they are able to win.

“I also look at physical abilities, because athleticism is also key in today’s tennis. When you have the three of them, you can go quite far.”

Why there’s more to come from Serena

They also need to have goals Mouratoglou believes in.

Away from coaching, he is looking to build UTS further and hopes to expand his academy operation to Asia and the US one day.

But his primary goal is to help Serena Williams equal and perhaps surpass Margaret Court’s all-time record of 24 Grand Slams, and Gauff and Tsitsipas to win their first of many.

“I’m always happy to help anybody but to give my all and a lot of time I need to have the same goals as the players.

“I will continue No1 with Serena because that’s the player I’ve worked with now for nine years. I want her to end her career having reached the last goal she wants to reach. And for the others, it’s to win Grand Slams and that’s OK for me.”

Now 39, Serena Williams has been on the brink of Court’s record for almost four years, but Mouratoglou believes there is more to come.

“They are all going to achieve their goals, all three of them, and I really believe it. And if I don’t believe it, they have to stop working with me straight away,” he says.

“They want to win Grand Slams, Serena also. So that’s what I think they will do, the three of them.”