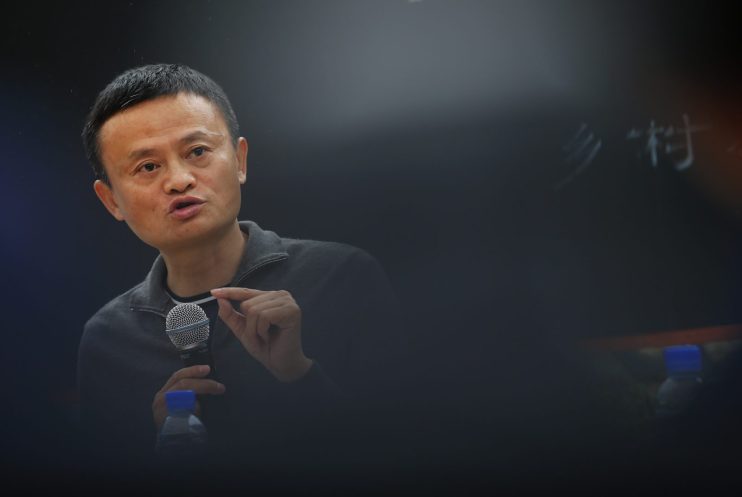

Has Jack Ma made IPOs a weapon of corporate warfare?

Ant Group is not a household name.

An affiliate of Chinese tech wizard Jack Ma’s Alibaba, it operates the digital payment platform Alipay, which serves more than a billion users and is China’s largest such enterprise.

This week, Ant Group announced the pricing of its listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and Shanghai’s Star Market at levels which revealed its IPO to be worth a record-breaking $34.4bn. This values the company as a whole at a staggering $310bn.

Alibaba itself went public on the New York Stock Exchange in 2014, raising $21.8bn, then the largest IPO in US history. Six years, it seems, is a long time in business.

Ant Group’s listing in Hong Kong and Shanghai is a coup for the Chinese government, which has been encouraging homegrown enterprises to register on the domestic exchanges rather than subject themselves to potentially uncomfortable scrutiny in New York or elsewhere. It is also an agreeable windfall for Jack Ma and a demonstration of the strength of his proposition: investors are hungry to be involved.

The previous record for an IPO was set last December, when the Saudi state oil company Aramco listed on Riyadh’s Tadawul exchange, raising $29.4bn. This was an important signal for the business, which had begun life in the 1930s as a joint venture between Standard Oil and the nascent Saudi state. The year 2019 had not been kind to oil prices, though the cataclysms of 2020 were yet to arrive, and, while the Kingdom was and is much involved in developing a carbon-free future, a demonstration of its underlying economic strength was welcome.

Alibaba, 2014; Aramco, 2019; Ant Group, 2020. Who’s next for that precedent-shattering IPO?

This is an important question, because in the great game of corporate flotations, the numbers are becoming as much totemic as they are a matter of rude financial health. It’s a trend seen across sectors: big-budget film releases need their opening weekends to be record-breaking if they are to hold their heads up in polite society, while every PR department knows the value of announcing the largest annual profits ever to indicate a company’s health and trajectory.

But is there a danger here? Could headline numbers become the target of an IPO, no matter what the underlying circumstances?

Let us look for a moment behind the Aramco flotation. The notion had been under consideration since 2016, when Saudi Arabia hoped to raise as much as $100bn by selling off five per cent of the company, to give foreign investors confidence in the Kingdom’s economic strength. But the dreaded “events” intervened: there were concerns about Aramco’s governance, oil prices began to head south, and Saudi Arabia went into relative purdah after the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul.

The eventual IPO, then, although still setting a new record, was in relative terms compromised. It was less than a third of its initially hoped-for value, and the gossip was that much of the sale had been supported by rich Saudis, sovereign wealth funds known to be sympathetic to the regime, and some state actors like China. One seasoned Brookings Institution panjandrum noted with a sniff that the IPO had achieved its goal of being the world’s largest, “but by an eyelash, instead of a landslide”. And, of course, its status lasted less than a year.

There is a potential conflict between sound finance and public relations. If the tag of “world’s largest IPO” becomes a must-have for every mega-flotation in the future to secure good publicity and bragging rights, boards and chief executives will need to be very careful that a potential “dash for growth” doesn’t come at any cost.

The next few months are unlikely to see any offerings on the scale of Aramco or Ant Group (though the markets are watching Airbnb closely), but there is undoubtedly a new chapter to be added to the corporate manual: how to shoot for the stars without shooting yourself in the foot.

Main image credit: Getty