Which stock markets look cheap as we enter the final quarter of 2020?

While the virus itself hasn’t gone away, as far as financial markets are concerned, the pit of misery was back in March. At that point, a typical global market stock market portfolio had haemorrhaged around a third of its value in just six weeks.

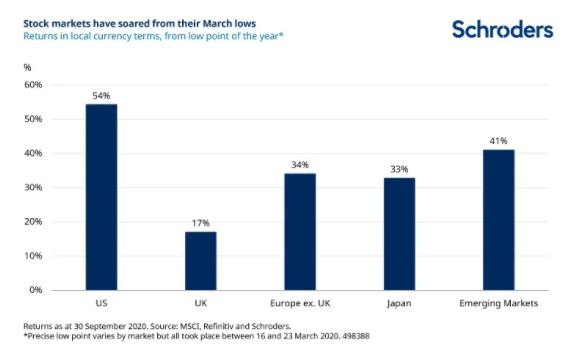

Stocks have soared

As is often the case, peak despair turns out, with hindsight, to create some fantastic buying opportunities. Markets have since soared (see chart). The problem is that it is so hard to stand aside from all of the emotional triggers that are going off in our heads during those times, as we wrote at the time.

Past Performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

While economic output and corporate earnings have collapsed

Shocking to many, this recovery has occurred while economic growth has collapsed, most companies’ earnings have dwindled, and payouts to shareholders been slashed.

However, as we have written before, a divergence between economic data and share prices is not as surprising as you might think. Stock markets are forward looking so the recovery partly reflects optimism that things will get better. In this instance, governments and central banks have also underpinned the recovery with their pedals to the metal on fiscal and monetary support.

Discover more:

– Learn: Would a Biden presidency hurt stock markets?

– Read: What’s driving stock market returns?

– Watch: Is Big Tech under threat?

Valuations are expensive

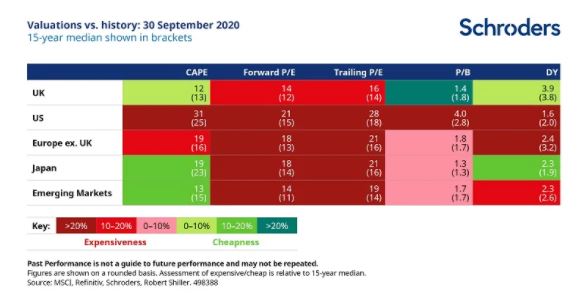

The big downside of share prices having run so far ahead of company fundamentals (e.g. earnings) is that, when we update our regular analysis of stock market valuations, it is not a pretty sight.

Whereas, back in mid-March, our valuation grid was a field of green, today it looks more like someone has spilled a glass of red all over the page. Of the 25 measures of stock market valuations in the table (five markets and five measures for each), 19 are in expensive territory. 12 are more than 20 per cent expensive compared with the median of the past 15 years (a brief explanation of each measure is given at the end of this article). Nothing looks especially cheap. Investors have to brace themselves for lower expected returns across the board.

What are the investment implications?

The US market stands out the most, being very expensive however you care to look at it. However, this in itself is not new. It has been expensive on valuation grounds for years but has continued to outperform other markets.

The FAMAG stocks – Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Google – have been beneficiaries of many trends which have accelerated this year: use of technology, cloud computing, working from home, online shopping and so on. In a world of low and falling growth, the impressive growth these companies have been able to deliver has been highly prized by investors.

However, current share prices bake in pretty heroic growth forecasts for the future and it remains to be seen whether they can deliver. Regulatory glare is also increasingly falling upon them. Risks abound and valuations are clearly expensive but it would take a bold investor to avoid the US entirely within a global stock market portfolio.

Valuations in other markets are cheaper, but they are far from being cheap historically. Something to consider is that, with the US representing almost 60 per cent of the global stock market (and 66 per cent of developed markets), many investors unconsciously have a lot of exposure to the US market at present. This may have served them well but, boring as it may sound, a portfolio that is more diversified on a geographic basis would be more robust to a range of potential outcomes.

Finally, a saving grace for stocks is that pretty much everything else looks expensive too. For example, cash rates and bond yields are depressingly low from an investment perspective. Investors have to put their money somewhere. This lack of attractive alternatives could help underpin stocks, despite unappealing valuations. It is also hard to see this changing any time soon.

The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the amounts originally invested

This information is not an offer, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or to adopt any investment strategy.

The pros and cons of stock market valuation measures

When considering stock market valuations, there are many different measures that investors can turn to. Each tells a different story. They all have their benefits and shortcomings so a rounded approach which takes into account their often-conflicting messages is the most likely to bear fruit.

Forward P/E

A common valuation measure is the forward price-to-earnings multiple or forward P/E. We divide a stock market’s value or price by the earnings per share of all the companies over the next 12 months. A low number represents better value.

An obvious drawback of this measure is that it is based on forecasts and no one knows what companies will earn in future. Analysts try to estimate this but frequently get it wrong, largely overestimating and making shares seem cheaper than they really are.

Trailing P/E

This is perhaps an even more common measure. It works similarly to forward P/E but takes the past 12 months’ earnings instead. In contrast to the forward P/E this involves no forecasting. However, the past 12 months may also give a misleading picture.

CAPE

The cyclically-adjusted price to earnings multiple is another key indicator followed by market watchers, and increasingly so in recent years. It is commonly known as CAPE for short or the Shiller P/E, in deference to the academic who first popularised it, Professor Robert Shiller.

This attempts to overcome the sensitivity that the trailing P/E has to the last 12 month’s earnings by instead comparing the price with average earnings over the past 10 years, with those profits adjusted for inflation. This smooths out short-term fluctuations in earnings.

When the Shiller P/E is high, subsequent long term returns are typically poor. One drawback is that it is a dreadful predictor of turning points in markets. The US has been expensively valued on this basis for many years but that has not been any hindrance to it becoming ever more expensive.

Price-to-book

The price-to-book multiple compares the price with the book value or net asset value of the stock market. A high value means a company is expensive relative to the value of assets expressed in its accounts. This could be because higher growth is expected in future.

A low value suggests that the market is valuing it at little more (or possibly even less, if the number is below one) than its accounting value. This link with the underlying asset value of the business is one reason why this approach has been popular with investors most focused on valuation, known as value investors.

However, for technology companies or companies in the services sector, which have little in the way of physical assets, it is largely meaningless. Also, differences in accounting standards can lead to significant variations around the world.

Dividend yield

The dividend yield, the income paid to investors as a percentage of the price, has been a useful tool to predict future returns. A low yield has been associated with poorer future returns.

However, while this measure still has some use, it has come unstuck over recent decades.

One reason is that “share buybacks” have become an increasingly popular means for companies to return cash to shareholders, as opposed to paying dividends (buying back shares helps push up the share price).

This trend has been most obvious in the US but has also been seen elsewhere. In addition, it fails to account for the large number of high-growth companies that either pay no dividend or a low dividend, instead preferring to re-invest surplus cash in the business to finance future growth.

A few general rules

Investors should beware the temptation to simply compare a valuation metric for one region with that of another. Differences in accounting standards and the makeup of different stock markets mean that some always trade on more expensive valuations than others.

For example, technology stocks are more expensive than some other sectors because of their relatively high growth prospects. A market with sizeable exposure to the technology sector, such as the US, will therefore trade on a more expensive valuation than somewhere like Europe. When assessing value across markets, we need to set a level playing field to overcome this issue.

One way to do this is to assess if each market is more expensive or cheaper than it has been historically.

We have done this in the table above for the valuation metrics set out above, however this information is not to be relied upon and should not be taken as a recommendation to buy/and or sell If you are unsure as to your investments speak to a financial adviser.

Finally, investors should always be mindful that past performance and historic market patterns are not a reliable guide to the future and that your money is at risk, as is this case with any investment.

Important Information: This communication is marketing material. The views and opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) on this page, and may not necessarily represent views expressed or reflected in other Schroders communications, strategies or funds. This material is intended to be for information purposes only and is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. It is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this document when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. The value of an investment can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed. All investments involve risks including the risk of possible loss of principal. Information herein is believed to be reliable but Schroders does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Some information quoted was obtained from external sources we consider to be reliable. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties, and this data may change with market conditions. This does not exclude any duty or liability that Schroders has to its customers under any regulatory system. Regions/ sectors shown for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. The opinions in this material include some forecasted views. We believe we are basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee than any forecasts or opinions will be realised. These views and opinions may change. To the extent that you are in North America, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management North America Inc., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of Schroders plc and SEC registered adviser providing asset management products and services to clients in the US and Canada. For all other users, this content is issued by Schroder Investment Management Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Registered No. 1893220 England. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.