The answer to Britain’s housing crisis is more houses – not risky mortgages

Housing experts were left scratching their heads this week after Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced his flagship policy to get young people on the housing ladder: bigger mortgages.

Johnson plans to turn “generation rent” into “generation buy” by offering long-term, fixed-rate mortgages of up to 95 per cent of the value of the home.

He is no doubt concerned by the shocking decline in the rate of homeownership amongst young people, who are becoming increasingly angry about spending much of their adulthood paying for their landlord’s mortgage.

Conservatives have already recognised that the decline of “property owning democracy” poses a risk for their electoral future. So making the saving process easier and boosting homeownership by dropping deposit requirements might seem sensible. There’s just one problem: it’s a terrible idea.

Let’s look at the economics of why homes are so expensive. Prices are set by supply and demand. Supply is very simple: it’s the number of homes available to buy or rent. The oft-misunderstood concept of demand means the extent to which people are willing and able to pay for them.

Read more: Boris Johnson announces plan for 95 per cent mortgages

It includes many factors, including the number and size of households, their incomes, and the availability and cost of mortgages.

When demand increases (for instance interest rates fall, making mortgages cheaper), developers have an incentive to build more, because there is more money to be made. This increases the supply, and prices should remain relatively stable.

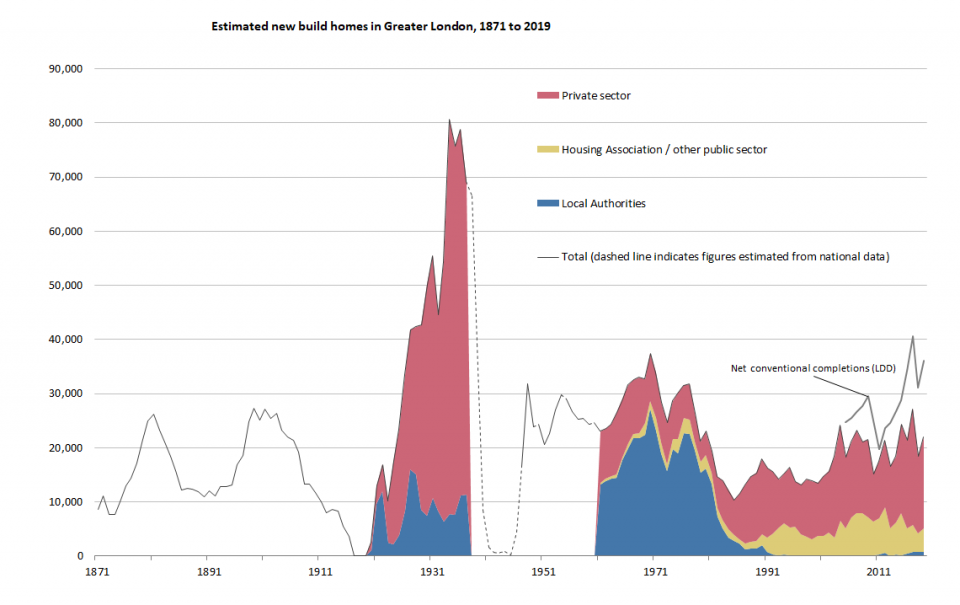

But this hasn’t happened. We’ve built far less over the last 30 years than we have for most of the last century. New supply peaked in London in the 1930s at 80,000 homes a year, and easily hit 30,000 for much of the post-war period. Since the mid-80s we’ve struggled to hit 20,000. While strong population growth, smaller households, higher incomes, and low interest rates have all fed into greater demand.

Compiled by GLA from:

– 1871-1937: Report of the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, via Quandl.com

– 1946-1960: GLA estimates based on national data from 1946 to 1960 (MHCLG, live table 244) and London’s share of the national total before World War II (from B. Mitchell, British Historical Statistics, p392) and after the war from the GLA and MHCLG data below

– 1961 to 1969: Annual Abstracts of Greater London Statistics

– 1970 to 2019: MHCLG house building statistics

Prices have skyrocketed

Accordingly, prices have skyrocketed. In 1970s London, an average home cost just £5,000 – or just under £78,000 in today’s prices. It’s now sitting at £486,000. That’s a 620 per cent increase. No wonder the kids can’t afford it!

Johnson’s plan does nothing to address the core problem: the supply of homes is not meeting the demand for them. It will simply lead to higher prices. Just as lower interest rates increased prices because the supply of homes didn’t rise in response, bigger mortgages will do the same.

Then there’s the other problem with 95 per cent mortgages. They’re risky. High loan-to-value mortgages dried up after the financial crisis to prevent riskier customers (those who can’t save a large deposit) being exposed to falls in prices. We’re facing another recession now. It is reckless to encourage young people to rush and buy at present high prices when that could leave them trapped in negative equity.

What should Johnson do instead? Rather than encouraging young people to further stretch the limits of their finances, he needs to stop letting prices rise. No one wants inflation in energy bills, food, or transport.

But when house prices rise, it’s somehow “growth” or a “strong market.” We need people to recognise it is absolutely not positive news for those who don’t already own. Government should explicitly target 0 per cent house price inflation, and ensure enough homes are delivered every year to meet that target.

Our planning system needs reform

The first challenge is boosting housing supply of all types and tenures, especially in high-demand areas like London. The main barriers to this relate to our planning system. It restricts the availability of land and turns every new development into a local political battle. Government is right to reform it into a simpler, rules-based system.

However, the most urgent need is for social housing. Current plans to divert funding to First Homes (discounted market sale homes) will help a lucky few who would probably buy soon anyway, but do nothing for the 8.4 million people who are in far higher need. Johnson needs to reverse these plans and invest in a new programme of social homebuilding to rival the post-war period.

Our property tax system is also a problem. Council tax is horrifically regressive, taking more proportionately from poorer households. Stamp duty discourages people from moving. These conspire to make staying cheap and moving expensive, gumming up the market and encouraging people to under-occupy. Johnson would do well to listen to the Fairer Share campaign and replace these taxes with a proportional property tax.

Finally, many people are going to be renting for much (or all!) of their lives. Government should get in renters’ good books by making this a less horrible experience.

They need to crack on with their promise to abolish unfair evictions, support renters to get redress from landlords and agents who fail to meet their contractual responsibilities, and fund proper enforcement of property standards. The political stakes are too high not to.

Read more: Finance chiefs warn against risky mortgage lending